A Brief History of Sunset Junction: Street Cars, Gay Rights and its Namesake Festival

With the recent decision by the L.A. Board of Public Works to deny the Sunset Junction Music Festival a permit, the thirty-year history of the neighborhood festival may be coming to an end. But Silver Lake's Sunset Junction—known for its unusual configuration and as a locus of fashionable cafes, bars, and shops—is steeped in local transportation and social history that will continue to survive in Southern California's archives.

Sunset Junction's name—as well as its peculiar layout—is a relic of L.A.'s heritage as a streetcar city. Rolling northeast from downtown Los Angeles on Sunset Boulevard, Pacific Electric Red Cars reached a fork in the tracks: they could continue on Sunset toward Hollywood Boulevard or turn west onto Santa Monica Boulevard toward the town of Sherman, better known today known as West Hollywood. The other street at the intersection, Sanborn Avenue, did not carry streetcar traffic but did add complications to the junction's layout.

Although it's universally known today as Sunset Junction, maps from the days of the Red Car, like the one below, actually mark the convergence of streetcar lines as the Sanborn or Hollywood Junction.

Trolley tracks first reached the intersection in 1895, when the Pasadena & Pacific Railway completed the first interurban rail line between downtown Los Angeles and the beachside community of Santa Monica. Ten years later, the junction was created when the railroad—by then renamed the Los Angeles Pacific—extended its tracks up Sunset Boulevard toward the fledgling town of Hollywood. Eventually, the original narrow gauge tracks were upgraded to standard gauge, and in 1911 the "Great Merger" of Southern California's competing interurban rail systems brought the junction under the jurisdiction of the Pacific Electric Railway.

The junction continued to serve as an important node in L.A.'s streetcar network until May 31, 1953, when the Pacific Electric shuttered its South Hollywood-Sherman Line, which traveled down the center of Santa Monica Boulevard. Streetcars continued to roam the Hollywood Line up Sunset until September 26, 1954, when buses replaced trolleys. Today, the tracks and electrical wires are gone, but an imaginative eye can still envision the trolleys making the wide, arced turn from Sunset onto Santa Monica.

Sunset Junction's role in the city's history did not end with the demise of L.A.'s streetcar system. Instead, later events at the junction, which became an epicenter for the burgeoning gay rights movement, would have national political and social significance.

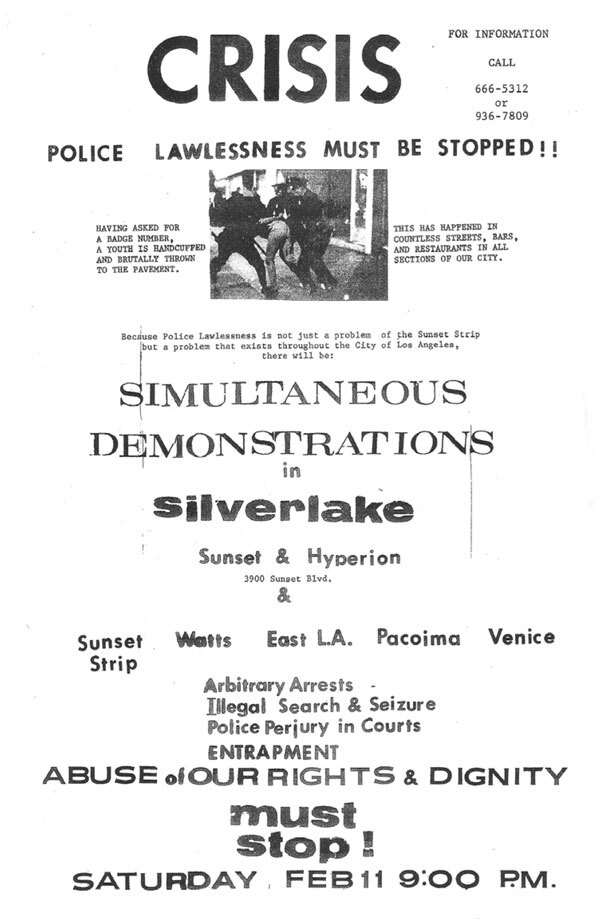

On New Year's Eve 1966, eight undercover LAPD officers infiltrated the gay-friendly Black Cat Bar, located near Sunset Junction between Sanborn and Hyperion Avenues. As the clock struck midnight and celebrants exchanged traditional New Year's kisses, police officers sprung into action, beating several bargoers and arresting 14 for assault and public lewdness.

The incident sparked one of the first public protests in the nascent gay rights movement. Six weeks later, and more than two years before the famous Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village, a crowd of hundreds gathered in front of the Black Cat to protest the raid. Attorneys and gay rights activists delivered speeches condemning "police lawlessness" and calling on authorities to respect the "rights and dignity of the homosexual citizen." Photos, documents, and other records from this watershed event are preserved in the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, now a part of the USC Libraries.

The demonstration did not end in violence—police monitored the protesters but kept a distance—and its peaceful success triggered further public rallies across the region.

It also had national ramifications. Two of the celebrants arrested on New Year's Eve, Charles Talley and Benny Baker appealed their conviction for lewd conduct (they were observed kissing each other, one of them wearing a white dress) to the U.S. Supreme Court. Although the high tribunal declined to hear their case, Talley's and Baker's attorney broke new ground by asserting equal protection rights under the 14th Amendment. The Black Cat protests also inspired Richard Mitch and others to create what is today the nation's best-known LGBT publication, The Advocate, as a way to spread information about the rising movement.

As Silver Lake grew in its reputation as a gay-friendly neighborhood, Sunset Junction continued to serve as an important place within L.A.'s LGBT community.

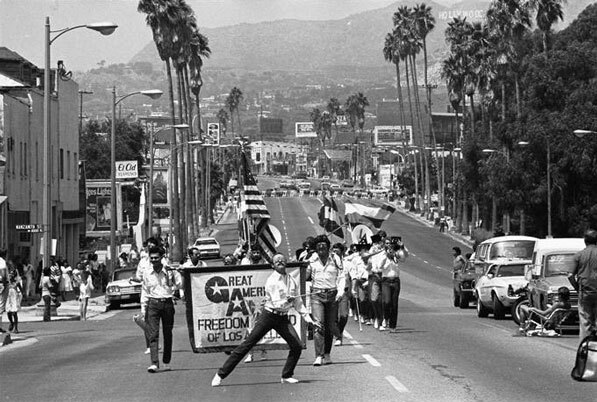

In 1980, community leaders organized the first-annual Sunset Junction Street Fair, designed to create bonds between LGBT residents and members of other cultural and ethnic groups in the area. The event was a hit, and every year from 1980 through 2010 Sunset Junction hosted the festival, which eventually evolved from a cultural outreach effort into a showcase for art and independent music. Although the street fair's future is now uncertain, its contribution to Sunset Junction's history—like those of the Pacific Electric Red Cars and the pioneering gay rights activists—will live on in our region's archives.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here will provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.