Rediscovering Downtown L.A.'s Lost Neighborhood of Bunker Hill

Among the charms of the monthly Downtown Art Walk is strolling through a rare historic L.A. neighborhood spared from the bulldozer. At this month's Art Walk, a new exhibition of photography from the George Mann Archives allows participants to discover a neighborhood to which fate and development have not been as kind: Bunker Hill.

Today's Bunker Hill -- an amalgam of commercial high rises, arts venues, other mega-projects -- is a product of a 1950s redevelopment scheme that cleared the historic neighborhood of all its structures, reconfigured its streets, and altered its topography. Some streets, like Clay Street and Bunker Hill Avenue, no longer exist. Others, like Olive Street, now rest several stories below where they once were. Except for the Angels Flight funicular and the odd leftover retaining wall, few physical traces of the original neighborhood remain.

But while the physicality of Bunker Hill has been erased, the city's architectural memories survive in libraries, official archives, and private collections. That record continues to inform scholarship about urban redevelopment and, through web-based historical research projects like On Bunker Hill, a public understanding of what the city lost when redevelopment claimed the hilltop community.

A Brief History of Bunker Hill

For much of Los Angeles' early history, Bunker Hill remained an unnamed, undeveloped promontory. The commanding views it offered of the surrounding landscape may have tempted sightseers to its summit, but the lack of a water delivery system kept the hilltop free of houses. It was not until 1867 that an enterprising French Canadian immigrant named Prudent Beaudry bought the land atop Bunker Hill -- at the reported cost of $51 -- and resolved to convert the scrub brush-covered promontory into a profitable real estate development.

First, Beaudry would need the city to extend its infrastructure up the slopes of the hill to serve his holdings. When the franchised water utility failed to share his confidence, Beaudry forged ahead on his own. Spurned by the Los Angeles Water Company, Beaudry constructed his own system of pipes and steam-powered pumps to deliver water to the hilltop from a reservoir below. He also built roads to connect the hill to the developed flatlands below and laid out streets atop the hill. One of them, which Beaudry named Bunker Hill Avenue in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Revolutionary War battle fought in Boston, eventually lent its name to the entire hilltop community.

All told, Beaudry reportedly spent $95,000 to improve Bunker Hill.

"I intend to spend money and keep on spending money in improvements and grading streets until this locality meets the attention it deserves," he said in 1877, "and it will not be long I assure you."

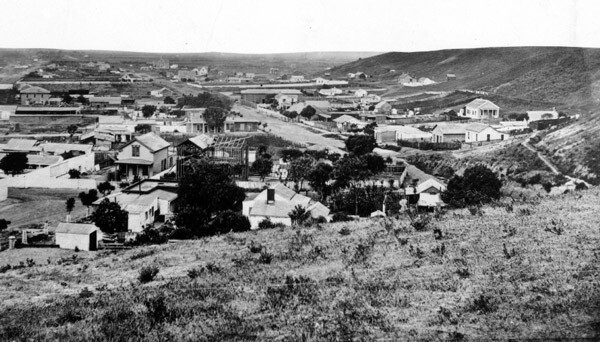

Beaudry was justified in his optimism; the modest two-story structures built in the development's early years soon gave way to grand Queen Anne mansions. A cable car railway on Second Street improved access to the hill, and by the 1890s, Bunker Hill had become the city's most fashionable residential district, attracting bankers, doctors, lawyers, and members of the city's social elite. Luxurious hotels like the Melrose, Belmont, and Richelieu opened atop the hill.

But by the time J. W. Eddy built the Angels Flight funicular in 1901, the neighborhood's fashionableness had already peaked. Apartment houses and commercial buildings began crowding out the Victorian mansions, whose occupants had moved on to more secluded neighborhoods like West Adams.

The rest of the expanding metropolis began to cast a skeptical eye toward Bunker Hill. Downtown business interests complained that the hill impeded the flow of traffic to the western suburbs. The construction of several tunnels -- the Third Street Tunnel in 1901, the Second Street Tunnel in 1924, and the Pacific Electric subway in 1925 -- alleviated the traffic problem, but other complaints only intensified over the succeeding decades. Denunciations of the neighborhood as a slum, in particular, closely tracked the gradual decline in the social status of its residents. Bunker Hill's appearance only gave more ammunition to its critics as new construction virtually stopped after 1920.

In 1928, C.C. Bigelow proposed removing the hill entirely using hydraulic mining equipment. The City Council referred the matter to Henry Babcock, an engineer who massaged Bigelow's audacious scheme into a slightly more modest proposal.

"In the instance of Bunker Hill the matter of topography enters largely into consideration," Babcock wrote in his report for the city. "Admittedly it is a traffic barrier not only for itself but for extensive and growing sections at every side of it. Architecturally it has not kept pace with the modernly growing parts of the city. It apparently presents a striking need for rehabilitation if it is to share in the indicated improvement in realty values. Modern engineering methods lend themselves expeditiously to the razing of this area or any part of it and without undue interference with a natural volume of traffic with the work is under way."

This circa 1940s drive through Bunker Hill was shot as stock footage for an unidentified feature film.

By the end of the 1940s, the city had gained the legal authority under the California Community Redevelopment Law of 1945 and the Federal Housing Acts of 1946 and 1949 to bring Babcock's plan to fruition. In 1948, the city created the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) and collected a mass of crime data, structural surveys, and other information (archived at the USC Libraries) that purportedly proved Bunker Hill's status as a blighted neighborhood. The city adopted the Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project in 1959, and within a decade the neighborhood was gone.

Rediscovering Bunker Hill

Now, Angelenos can revisit the lost neighborhood of Bunker Hill through the color photography of George Mann, on display at the Take My Picture Gallery starting this Thursday, July 12. A special presentation on the story of Bunker Hill will accompany the opening.

Mann, a former vaudeville performer who later turned to professional photography, brought his camera to Bunker Hill in the 1950s to capture the neighborhood on film before it fell to the forces of urban development.

Mann originally displayed his photos in special 3-D viewers that he leased to Los Angeles-area restaurants and doctor's offices. But after his death in 1977, the negatives sat in obscurity for years, until, in 1992, his daughter-in-law Dianne Woods discovered them in her basement.

Woods said she was "awestruck" upon finding the photos.

"I spent the next two weeks poring over this incredible body of work and repacking each film strip into proper archival sleeves," said Woods, who resolved to earn Mann recognition as a significant American photographer. "Being a commercial photographer by trade it was easy to see, even in negative form, what was in front of me."

Carefully restored, Mann's photography -- the largest known collection of color photography related to Bunker Hill -- can now be incorporated into the neighborhood's historical record.

According to exhibition host Kim Cooper of Esotouric and the Los Angeles Visionaries Association, the full-color photos challenge the narrative of urban decay that justified Bunker Hill's razing.

"Yes, there are signs of dereliction in some of the photographs," Cooper said, "but as a whole this unposed portrait of the many faces of Bunker Hill could not be further from the 'slum-ridden slopes' smear which was perpetuated by the Los Angeles Times and other pro-development voices who sought to benefit from Federal grants and increased tax revenues.

"Taken as a whole," she continued, "these photographs give us a powerful sense of Bunker Hill as a mature neighborhood -- not just a single lonesome Victorian captured against a brooding sky or the stylized black-and-white shadow play of a film noir location or the fantasy of a Leo Politi illustration -- but a sunny, walkable, appealing community of mature gardens, handsome and varied buildings, shortcuts, cats, strolling retirees, ample parking and stunning views out over the city. You cannot see these photos without longing to walk the streets or live in one of the buildings."

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.

Update, July 12, 2012: An earlier version of this post incorrectly stated that the mansion known as the Castle burned before being relocated to Heritage Square. In fact, it was moved to Heritage Square in 1969 and then burned shortly thereafter.