The Lost Wetlands of Los Angeles

What did the L.A. Basin look like before there was a Los Angeles? A common misconception – one that resonates with genuine concerns about the city's aridity and reliance on imported water – is that the city's natural state is desert. But early accounts of the landscape painted a different picture, depicting a patchwork of grassy prairie, wetland, scrub, oak woodland, and dense willow thickets where freeways, office towers, and houses stand today.

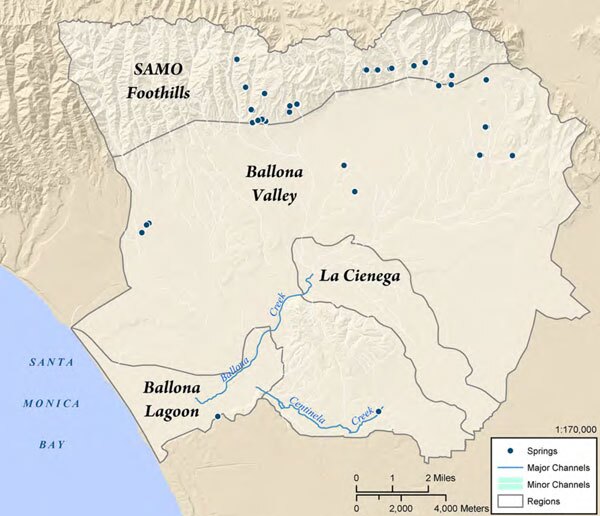

Recently, a team of scientists, geographers, and other researchers released a report for the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project that reconstructs the historical landscape of the Ballona Creek watershed – a 130-square-mile swath of land home to more than 1.2 million people that includes much of western Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, Inglewood, South Los Angeles, and the Baldwin Hills. Piecing together clues gleaned from survey reports, photographs, maps, and other archival documents, the researchers created a detailed map of the region's historical ecology, identifying lost habitats and the flora and fauna that once lived there.

What the researchers found might surprise most Angelenos: the watershed was home to more than 14,000 acres of wetlands, ranging from freshwater ponds to alkali flats, from willow thickets to meadows, and home to a diversity of migratory and resident birds. Elsewhere, seasonal streams coursed through the Ballona Valley, fed by springs in the Hollywood Hills and in the flatter lands below. Two perennial streams, Ballona and Centinela Creeks, flowed toward the Santa Monica Bay.

The Ballona Creek Watershed Historical Ecology Project report focuses on the years between 1850 and 1890, before European settlement had completely transformed the land. Watersheds are dynamic systems, and during this time the Ballona Creek watershed was in a state of flux. In 1825, some combination of torrential flooding and earthquakes shifted the course of the Los Angeles River: while it previously flowed west through what is today the channel of the Ballona Creek, in 1825 it jumped its banks and began flowing south to the San Pedro Bay. The entire Ballona Creek watershed, then, was still adjusting to the reduced water flow when California entered the Union in 1850.

One major wetland complex, which the researchers name La Cienega, occupied a depression in the basin. Fed by above-ground streams and subterranean water flow, this complex of meadows, ponds, marshes, and pools stretched from Mid-City Los Angeles to South L.A. A large pond was only a stone's throw away from the present-day intersection of Florence and Normandie. North of the complex, in present-day Beverly Hills, a network of streams flowed from the Hollywood Hills into a large area dominated by sedges and rushes. Part of the Spanish name for these meadows—Rodeo de las Aguas, or Round-up of the Waters—lives on in the name of Rodeo Drive.

La Cienega was connected to the region's other major wetland complex, Ballona Lagoon, by the roughly five-mile stretch of Ballona Creek. (Converted into a concrete storm channel in 1935, Ballona Creek now extends an additional four miles into what were once open wetlands.) Where sailboats dock today in Marina Del Rey was historically a vast system of tidal marshes and salt flats. Further inland, the meadows of the lagoon stretched into modern-day Culver City. A line of sand dunes abutted the sea, and a long, narrow strip of open water named Ballona Lake once welcomed boaters. Tidal influence on the lake was intermittent, the report explains:

The migration of the Los Angeles River away from the lagoon transitioned the system into a lower energy system where only on rare occasions was there enough freshwater flow from Ballona Creek to break through the buildup of sediment along the coast. As a result, gradual build up of sediment around the terminus of the previous estuary formed dunes and created this "trapped" lake-like feature.

In other places, remnants of the historical landscape remain. Kuruvungna (Serra) Springs, long a reliable water source for the region's native Tongva people, still gushes from the ground today on the campus of University High School. To the east, part of a freshwater pond dating from prehistoric times survives as MacArthur Park Lake.

Reconstructing the watershed's lost landscapes was only possible through meticulous historical detective work. The researchers consulted 84 source institutions—many of them members of L.A. as Subject—in search of maps, photographs, and written accounts that provided clues about the region's historical ecology.

"The use of multiple archives, including specialized repositories such as those housing ornithological collections, aerial photographs, or maps, was central to our approach to the historical ecology of the Ballona watershed," said Travis Longcore, one of the report's co-authors and the science director of the Urban Wildlands Group.

For example, the researchers found evidence of a vernal pool (filled only intermittently with water) in an 1893 note by surveyor Alfred Solano, found in the Huntington Library's Solano Reeves Collection: "In the Northwest corner of the parcel secondly described in said order of partition, I found a depression cover about sixteen acres, which was filled up by the rains in winter so as to render it unfit for either cultivation or pasture."

Similarly, detailed irrigation maps by William Hammond Hall—preserved in the California State Archives—pointed to historical features of the landscape, while a photo from the Los Angeles Public Library's collections showed a boater enjoying the open water of Ballona Lake.

The team then georeferenced its clues, entered them into GIS software, and estimated their confidence in each feature on the resulting map.

Now, the researchers' work will inform not only projects to restore lost habitats, but also, as Southern California increasingly focuses on local versus imported water sources, efforts to manage local watersheds in a sustainable and ecologically responsible way.

"Ecological reconstructions do not provide a direct template for the future, but they can help explain the types of habitats that would be found with natural precipitation and drainage patterns or identify habitats that are no longer found on the landscape," said Longcore, who is also an associate research professor at USC's Spacial Sciences Institute and an associate adjunct professor at UCLA's Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

"In the case of the Ballona wetlands it can help decision makers to understand that the current proposals are not 'restorations' in the sense that they are not returning the system to a condition prior to disturbance," he explained. "The current proposal would create a tidal connection similar to that found found one to two thousand years ago when the wetland area was completely open to the ocean all year—when the L.A. River flowed out through Ballona—instead of the conditions in the 1800s (and which would be supported by the smaller watershed today) in which the tidal connection to the ocean was much more limited and seasonal. Whether this influences the current plans or not remains to be seen."