How El Camino Real, California's 'Royal Road,' Was Invented

Along Highway 101 between Los Angeles and the Bay Area, cast metal bells spaced one or two miles apart mark what is supposedly a historic route through California: El Camino Real. Variously translated as "the royal road," or, more freely, "the king's highway," El Camino Real was indeed among the state's first long-distance, paved highways. But the road's claim to a more ancient distinction is less certain. In fact, the message implied by the presence of the mission bells – that motorists' tires trace the same path as the missionaries' sandals – is largely a myth imagined by regional boosters and early automotive tourists.

The message implied by the presence of the mission bells – that motorists' tires trace the same path as the missionaries' sandals – is largely myth.

Although the definite article in the road's name suggests otherwise, California's El Camino Real was just one of many government roads that stretched through Spain's New World empire. These highways linked Spanish settlements in far-flung provinces to administrative centers. One well-established trail in Baja California preceded Alta California's by several decades. Another extended from Mexico City to Sonora and thence to Santa Fe.

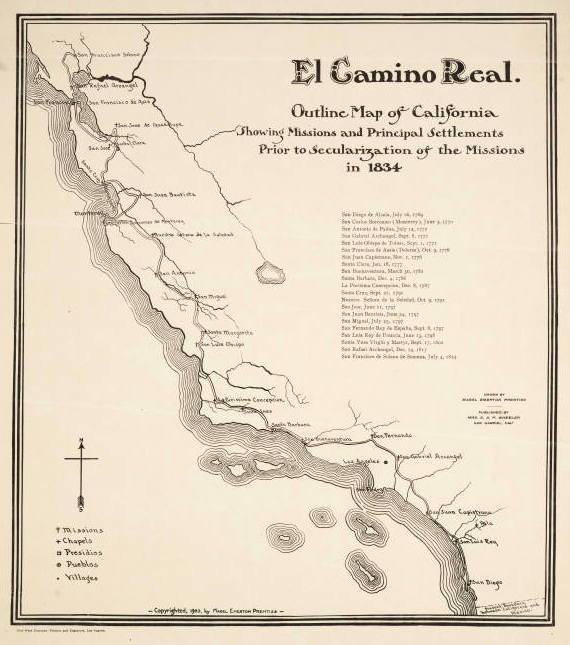

In Alta California, one such road helped link the presidios (military forts), pueblos (civil towns), and religious missions that Spain furiously began building in 1769 to parry the territorial ambitions of Russia and Britain. But the stories told today about the footpath diverge from its actual history. The road's exact route was not fixed; the actual path changed over time as weather, mode of travel, and even the tides dictated. Furthermore, while the road provided local transportation links between colonial settlements, the primitive highway was eclipsed in importance by a coastal water route between Alta California's south and north. Ships rather than the so-called royal road usually transported goods and passengers over long distances.

By the late nineteenth century, although local segments of the old trail were still heavily used, the route as a whole had faded into obscurity.

As Phoebe S. Kropp explains in her book "California Vieja," it took the convergence of two powerful trends at the turn of the twentieth century to transform El Camino Real from an forgotten pathway into a main-traveled road.

The first was the rise of the automobile, which created a small but influential group of wealthy Californians who clamored for a well-maintained state highway.

Regional boosters saw California's missions – many of them long-neglected and crumbling into ruin – as a place where tourists could commune with California's romantic past from the comfort of their modern machines.

The second was a reinterpretation of Spanish colonial California as a romantic paradise, fueled by the 1884 publication of Helen Hunt Jackson's "Ramona" and set within a broader cultural embrace of Southern California as a American Mediterranean retreat – "Our Italy," as Charles Dudley Warner titled his 1891 book on the region. Regional boosters saw California's missions – some of which still functioned as parish churches, but many of them long-neglected and crumbling into ruin – as a place where tourists could commune with California's romantic past from the comfort of their modern machines. To clothe El Camino Real with mythic significance, they invented sentimental stories about Franciscan fathers traveling along the road from mission to mission, which were supposedly spaced one day apart along the trail.

Today's El Camino Real is largely a "booster myth," says Matthew Roth of the Automobile Club of Southern California Archives.

"There might have been some kind of more or less continuous footpath, but it was not a regularly traveled thoroughfare," Roth explains. "El Camino Real was a product of the same impulse that gave us the Spanish Colonial Revival in architecture – imparting an exotic hue to the region as a way to attract more tourists and settlers."

Spearheaded by Los Angeles writer and activist Harrie Forbes and backed by groups like the Auto Club, the California Federation of Woman's Clubs, and the Native Daughters of the Golden West, efforts to refashion El Camino Real into a tourist highway gained steam in the first decade of the 20th century.

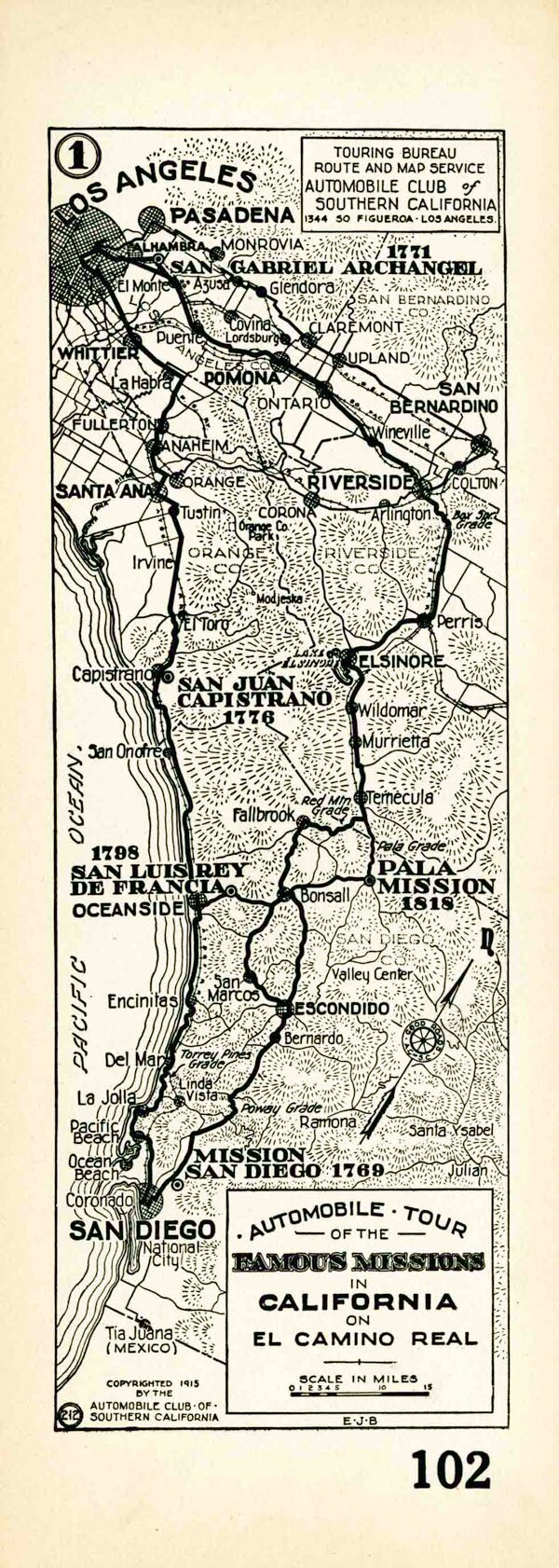

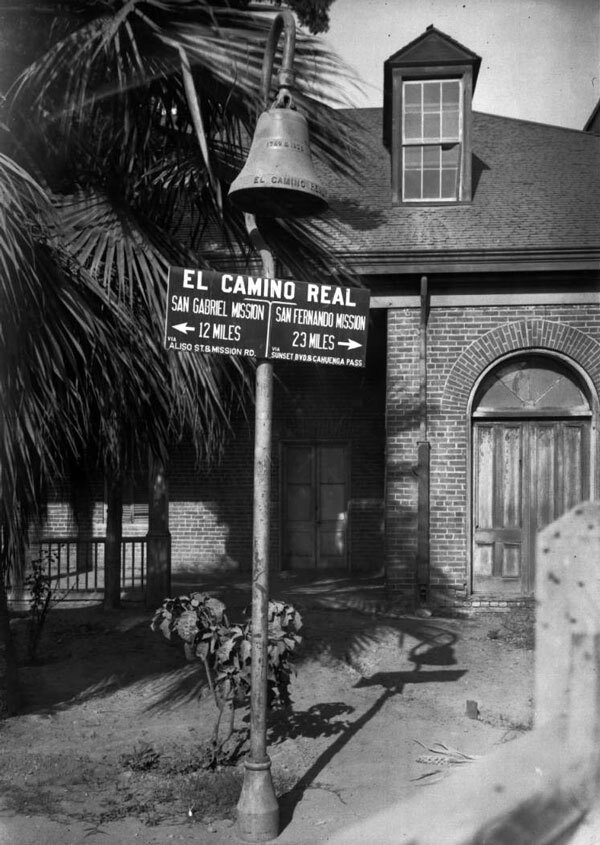

In 1904, supporters organized the El Camino Real Association to mark the historical route, promote tourism along the road, and lobby for government support. The actual, historical route – which had shifted many times, in any case – often evaded the association's trackers. But between 1906 and 1914, the association succeeded in placing more than 400 roadside markers along an approximation of the original footpath.

Consisting of a bell fashioned after those at Los Angeles' Plaza Church, and hung from a pole resembling a shepherd's staff, the markers assured motorists that they were on the correct route, often indicating the distance in miles to the nearest mission. (The markers were the design of Forbes, who with her husband owned the only bell foundry west of the Mississippi.) Auto Club strip maps, reproduced above, provided another invaluable aid to tourists.

The roadway itself fell short of expectations at first. While the 1910 State Highways Act authorized construction of a paved road along the route of El Camino Real, construction lagged and for many years much of the historic road remained only a primitive trail. Between cities there were streams to ford and steep grades to scale. Sometimes, teams of horses would rescue automobiles trapped in mud. Finally, by the mid-1920s, the highway construction was complete, and in 1925 the state legislature designated much of it as U.S. Highway 101.

Although theft and vandalism have claimed many of the original bells, Caltrans recently replaced the missing roadside markers along the entire entire route from San Diego to San Francisco. Today, mission bells continue to guide motorists along the route, silent about its historical authenticity.