Canoga Park at 100: A Brief History of the Birth of Owensmouth

One hundred years ago last Friday, a town named Owensmouth was born on the barley fields of the San Fernando Valley. "Like an eaglet bursting asunder the egg which nourished its embryonic life," the Los Angeles Times gushed in its coverage the following day, "Owensmouth yesterday pipped the shell of the universe and spread its bright young pinions in the glory of the sun."

Founded on March 30, 1912, the settlement -- renamed Canoga Park in 1931 -- represented one of L.A.'s first steps in a march that eventually transformed the San Fernando Valley from farmland into suburbia.

Owensmouth was at the vanguard of a land boom in the San Fernando Valley. For decades, two factors prevented development in the Valley: its remote location, separated by the Santa Monica Mountains from the population and business center of Los Angeles; and the opposition of a few large landholders, who preferred to maintain the valley for agricultural use. Some suburban settlements ringed the valley from Calabasas to Burbank, but wheat fields, orchards, and ranch lands predominated.

By the end of the twentieth century's first decade, however, the climate had changed. Electric railways and growing popularity of automobiles shrunk the distance between the city and the Valley, and heightened expectations of population growth and agricultural fecundity -- fueled by the imminent arrival of water from the Owens Valley -- boosted land values. One landowner, Isaac N. Van Nuys, was willing to sell. The aging farmer, banker, and land baron controlled the Los Angeles Farming and Milling Company, which owned a vast tract totaling 47,500 acres and constituting much of the southern half of the San Fernando Valley.

In 1909, Van Nuys sold his farmland for $2.5 million to a syndicate named the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company. The syndicate's Board of Control comprised Los Angeles' leading movers-and-shakers: Title Insurance and Trust Company head Otto F. Brant; Los Angeles Times business manager Harry Chandler, a friend of Van Nuys'; Times owner Harrison Gray Otis, Chandler's father-in-law; transit magnate Moses H. Sherman; and developer Hobart Whitley, hailed today as the "father of Hollywood." Thirty participants drawn from L.A.'s business elite joined the board members as investors.

Critics characterized the purchase as a land grab and accused the syndicate of coercing the city into building the aqueduct for its own benefit. (This criticism resounds in later fictional works like "Chinatown.")

Ignoring the public outcry, the syndicate promptly set about improving its land and preparing it for development. At a cost of $500,000, it built the valley's first east-west thoroughfare: Sherman Way. A divided highway with a private Pacific Electric right-of-way running down its center, Sherman Way connected the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company's three planned townsites.

The first was Van Nuys, founded in 1911 and named in honor of the land's former owner. Further west would be Marian, named after Marian Otis Chandler, Otis' daughter and Chandler's wife. Marian, later renamed Reseda, was subdivided in 1913. At the western extreme of the syndicate's landholdings would be Owensmouth, named in hopeful anticipation of Owens River water that would soon spill into the San Fernando Valley by way of the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

Owensmouth's associations with water long predated plans for the aqueduct. The town was located on the site of an old well used in by stagecoaches and local settlers. When the Southern Pacific built a branch line through the area, it designated the spot Canoga, after the town of Canoga, New York, which in turn took its name from the Indian village of Ganogeh ("place of floating oil").

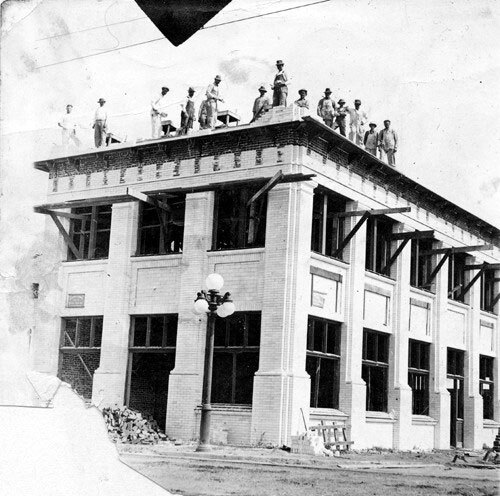

The Janss Investment Company, which the syndicate hired to subdivide Owensmouth, platted the town around the junction of the Southern Pacific tracks and Sherman Way. Throughout 1911, as construction on Sherman Way raced westward from Van Nuys, workers rushed to provide the planned town with its basic needs: a water tower capable of supporting a population of 10,000, according to the syndicate's claims; a passenger depot along the Southern Pacific line; and a mission-style building where Janss could sell lots.

On April 30, 1911, the Janss Company placed its first advertisement for Owensmouth in both the Los Angeles Examiner and the Times. Accompanied by a drawing that depicted a pastoral valley framed by oaks, the ad proclaimed: "The Wheels of Progress Are Now Hastening to Completion One of the most Gigantic Land Undertakings Ever Operated in the West."

Eleven months later, Owensmouth was ready for the public eye. The Janss Company organized an extravagant celebration featuring a free barbecue, an air show, and live music. The highlight of the day's festivities was to be a race between a biplane and a Fiat sports car. In the days leading up to the event, the Times ran daily booster stories hyping the festival and promising an "auspicious beginning" for the new town.

On March 30, 1912, Santa Ana winds kicked up dust and rattled nerves, but the town's opening festival was a success. The Janss Company sold $104,100 in land the first day. Local artist Jeanie S. Peet was the first buyer, paying $1,000 for a lot for her studio. Other purchasers -- 25 out of 151 -- traveled from out of state.

In its coverage under the headline, "Stork's Happy Call to the Golden Vale," the Times struck an optimistic tone: "Captains of industry who belong to the master builders of the Western Empire made the new town, but God alone could have fashioned its site, as only He could have made the perfect day which marked its bright beginning."

Despite the Times' optimism, Owensmouth struggled through its first few years. Electricity did not arrive until 1913; natural gas came years later. By 1916, only 200 residents called the four-year-old town home, and residents and farmers could not enjoy the water to which their town's name referred; only after Los Angeles annexed Owensmouth in 1917 did aqueduct water flow into town and into the surrounding orchards and citrus groves.

In the late 1920s, residents and business leaders suggested that their town's name revert back to Canoga, complaining that Owensmouth suggested a location hundreds of miles away in the Owens Valley. Concerns about the community's image may have inspired the campaign, too; the older suburbs of East Los Angeles and Sherman had recently changed their names to Lincoln Heights and West Hollywood, respectively. In 1931, Owensmouth became Canoga Park. (The Post Office insisted on adding "Park" to avoid confusion with Canoga, New York.)

Today, Owensmouth's original town plat merges with the sprawling street grid of the San Fernando Valley, and its name was dropped from official use decades ago. Still, reminders of the community's origins remain. Owensmouth Avenue runs north-west through the Valley, and Vanowen Street, a portmanteau of Van Nuys and Owensmouth, still traverses the former lands of the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.