At First and Beverly, A Freeway Bridge Out of Nowhere

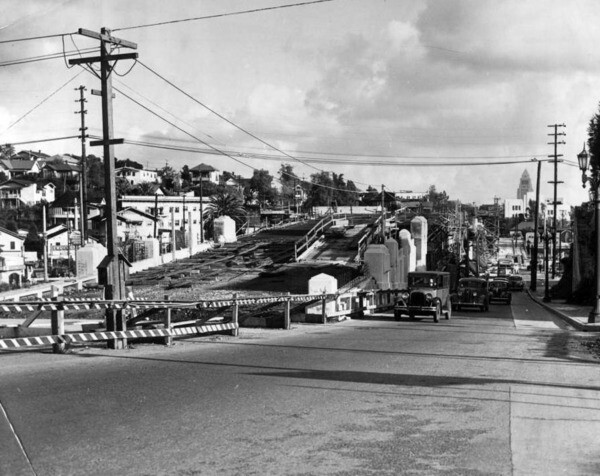

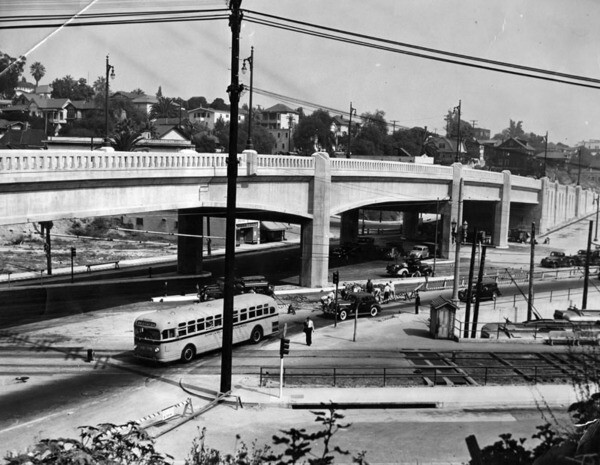

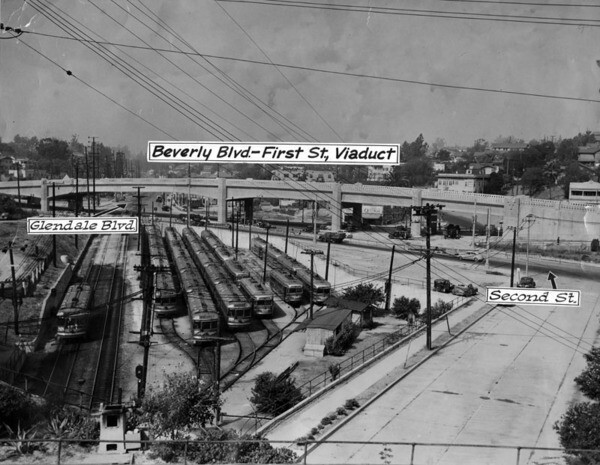

The First Street-Beverly Boulevard Viaduct over Glendale Boulevard is something of an infrastructural anomaly -- a 900-foot bridge better suited for a freeway interchange than an intersection of mere surface streets. And yet its massive scale answered several practical traffic problems at the site. Before the viaduct's construction in 1940-42, no fewer than six streets and four trolley tracks converged at a complicated crossroads. Two of the roads, First Street and Beverly Boulevard, dropped suddenly from higher ground into an ancient, paved-over arroyo. When it opened in September 1942, the viaduct directly linked First with Beverly, allowing east-west traffic to soar over the stream channel and twisted intersection altogether.

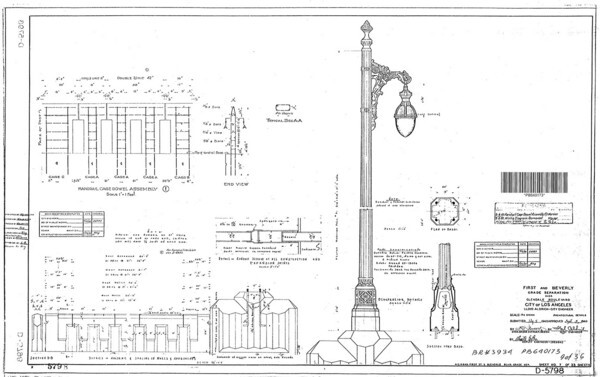

The reinforced-concrete bridge -- built with funding from the Depression-era Works Progress Administration -- does bear more than a superficial resemblance to freeway architecture. In ornamentation, its design by Ralph W. Stewart represents a transitional form between the Art Deco flourishes of Merrill Butler's Sixth Street Bridge (1932) and the naked brutalism of modern freeway structures. Blank concrete faces below the bridge's deck give way to decorative, rectangle-windowed balustrades above. Geometric patterns adorn the bridge's pylons, and, before standard streetlights replaced them, ornate, almost-rococo electroliers hung from fluted light poles.

The viaduct also boasts common ancestry with Los Angeles' earliest freeways. As Auto Club historian Matt Roth recounts in "Concrete Utopia" (available online through the USC Digital Library), it was part of a larger program among city traffic engineers to overcome traffic congestion through new technologies like grade-separations and limited-access roads. In places, state-funded projects incorporated these earlier city efforts into modern freeways. The Arroyo Seco Parkway (CA-110), for example, passes beneath grade separations built for Figueroa Street, and a stretch of the San Bernardino Freeway (I-10) were born as limited-access Ramona Boulevard.

The viaduct linking First with Beverly nearly became part of a modern highway itself. In 1936 the city planning commission considered a plan to upgrade First Street into a "semi-freeway" between Glendale Boulevard and downtown. Later, city and state engineers considered routing the Hollywood Freeway (US-101) south of its eventual location -- a route that might have co-opted the viaduct as a freeway overpass. But First Street never graduated beyond the level of a humble surface road, and the viaduct remains a remnant of past transportation visions. "It still stands there today," Roth writes, "an isolated piece of freeway technology, grotesquely out of scale with its surroundings, awaiting the linkages that never came."

L.A. as Subject is an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, cultural institutions, and private collectors. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region..