A Brief History of the Los Angeles Plaza, the City's Misplaced Heart

Modern Los Angeles is a city without a center. Nodes of power, prestige, and commerce dot the landscape, even if the skyscrapers of Bunker Hill mischievously invite the viewer to locate the city's center there. In its early years, however, Los Angeles was built around a well-defined center, the Plaza, which remained its political, social, and commercial heart even as it grew from a Spanish colonial outpost into a booming Yankee city.

The Plaza preceded the city. It was prescribed in detail by the very law that authorized the founding of Los Angeles as Spanish California's second civilian pueblo: Governor Felipe de Neve's Reglamento, written in 1779 and ratified by the Spanish king in 1781. This list of regulations, which represents L.A.'s earliest urban planning document, directed the pueblo's founding colonists to build their houses around a rectangular plaza of 200 by 300 feet, its corners aligned with the cardinal directions of the compass.

Neve's order did not represent an innovation; the concept of a plaza at the center of Spanish colonials settlements dates back to the 1542 Laws of the Indies. Some scholars even suggest that the Spanish inherited the idea from the grand public square in the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlán. Thus, when los pobladores arrived in the broad river valley just south of the Arroyo Seco's confluence with the Los Angeles River (then known as the Porciuncula) in the summer months of 1781, the plaza they constructed was already a legacy of past imperial dominion.

Nevertheless, Neve's plaza is not the Plaza that exists today. In the pueblo's infancy, the plaza moved once and, some historians suggest, twice, in response to the raging torrent of the Porciuncula. Before engineers had shackled the river in concrete, the stream's course was uncertain. A major flood in 1815 shifted the river's course from the eastern to the western edge of the valley. (Downstream, the river jumped its banks ten years later and carved a new channel south to San Pedro, leaving behind Ballona Creek as a remnant of its former course.)

With floodwaters lapping at their doorsteps - and at the cornerstone of what would become Iglesia Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles - the Angeleños decided to move both the plaza and the church to higher ground. The whitewashed adobe church opened at its present location in 1822. The town then proceeded to create a new Plaza facing the church. That task took years to complete, since houses and other structures stood on or abutted the lot selected for the Plaza. Its principal phase was completed in 1825, but it was not until 1838 that the new Plaza achieved a generally rectangular shape. On its north, south, and east sides adobes belonging to the city's most prominent residents - Pío Pico, Vicente Lugo, José Carrillo - fronted the Plaza. On its west side stood the church and government buildings.

Over the next few decades, the Plaza remained the center of civic life in Los Angeles, even as the flag flying over the town's government house changed from the Spanish imperial banner to the Mexican tricolor and, later, to the Stars and Stripes. In 1835 Mexico promoted the pueblo to a ciudad and designated Los Angeles as the capital of California. In its new role as the public square of a territorial capital, the Plaza hosted two gubernatorial inaugurations: that of Carlos Antonio Carillo in 1837 and of Manuel Micheltorena in 1842.

The Plaza was also an important commercial center in Mexican Los Angeles. Three important roads met at the Plaza: El Camino Real, which linked the Spanish settlements of California; the road to the port of San Pedro; and the trade road to Santa Fe. Merchants often set up shop in the Plaza, laying out handcrafted goods from New Mexico, the United States, and other far-off lands.

In 1847, American troops under the command of Commodore Robert Stockton marched up Calle Principal into the Plaza, their brass band playing "Yankee Doodle." Stockton would make his headquarters in the adobe of Encarnacion Avila, who had fled to the nearby house of friend Jean-Louis Vignes. (The Avila Adobe, which still stands today on Olvera Street, welcomed another intrepid figure from U.S. history in 1826 when fur trapper Jedediah Smith stayed as the guest of Encarnacion Avila and her husband, Francisco.)

In its early years, the Plaza was a dusty open space crossed by wagon ruts, devoid of landscaping. Animals often wandered through the square, and open farmland lay only a stone's throw away. A small brick structure in the center served as L.A.'s first water reservoir. German-Jewish immigrant Harris Newmark, who first saw the Plaza in 1853, described it this way:

"There was no sign of a park; on the contrary, parts of the Plaza itself...were used as a dumping-ground for refuse. From time to time many church and other festivals were held at this square...but before any such affair could take place--requiring the erecting of booths and banks of vegetation in front to the neighboring houses--all rubbish had to be removed, even at the cost of several days' work."

By 1870s, the Plaza and the surrounding area had developed a reputation for vice and violence--at least among the city's Anglo population. The infamous Calle de los Negros--given an unprintable English appellation--was home to several gambling dens and in 1871 was the site the vicious Chinese Massacre, in which a mob of 500 white men murdered 19 Chinese men and boys.

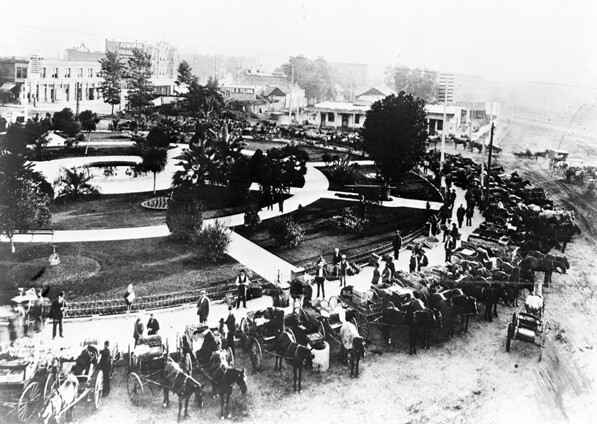

City leaders were making a concerted effort to revitalize the Plaza, though. Pío Pico opened his upscale hotel, Pico House, on the Plaza's south edge in 1870. The next year, the city removed the brick reservoir, installed a fountain, and built a circular walk in the middle of the Plaza. Four years later, flowers and trees were added, followed soon by the planting of two Moreton Fig trees that still shade the Plaza today.

Despite the new park-like appearance, the Plaza soon ceased to be the center of town for L.A.'s ascendant Anglo population, who established a downtown south and west of the old Plaza. St. Vibiana's Cathedral opened in 1876 at 1st and Main, and most English-speaking members of the Plaza Church congregation migrated there. Adjacent to St. Vibiana's, the Temple Block and Stearns Block developments became the commercial heart of the city. In 1889, City Hall moved to a site at Broadway and 2nd, further alienating the traditional heart of the city from civic life. In the 1890s, the park at 6th street formerly known as the "Lower Plaza," which we know today as Pershing Square, was re-ordained Central Park. By the 1940s the alienation was complete with the construction of the 101 freeway, which - though sunken in its trench - represents a physical and mental barrier between the old Plaza and the modern civic center.

Still, the plaza remained an important cultural center through the years for those left outside the social mainstream. Immigrant neighborhoods like Sonoratown and Chinatown ringed the old Plaza, while socialists staged rallies inside the old Spanish heart of Los Angeles.

In the 1920s, the Plaza was in jeopardy. Historic adobes were being lost to neglect. At least one early plan for Union Station located the rail passenger terminal on the site of the Plaza. But the plaza was at once saved and transformed in 1930, when Christine Sterling, aided by Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler and other civic boosters, converted a back-alley adjacent to the Plaza into a tourist marketplace. Her creation, Olvera Street, has since drawn millions of tourists to the historic area. Although Sterling's vision was distorted by a romantic notion of L.A.'s Spanish past, her efforts secured the future of the Plaza. Today, the Plaza still functions as an important multi-cultural space, crowded year-round with public events and festivals.

As California historian Kevin Starr wrote, "Olvera Street might not be authentic Old California or even authentic Mexico, but it was better than the bulldozer."

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.