When Pepper Trees Shaded the 'Sunny Southland'

Today, it's hard to imagine Southern California without palm trees. They line our streets, shade our gardens, and guest-star in films to establish Los Angeles as the setting. But before the lanky palm conquered the L.A. skyline, another tree played the same metonymic role: the pepper.

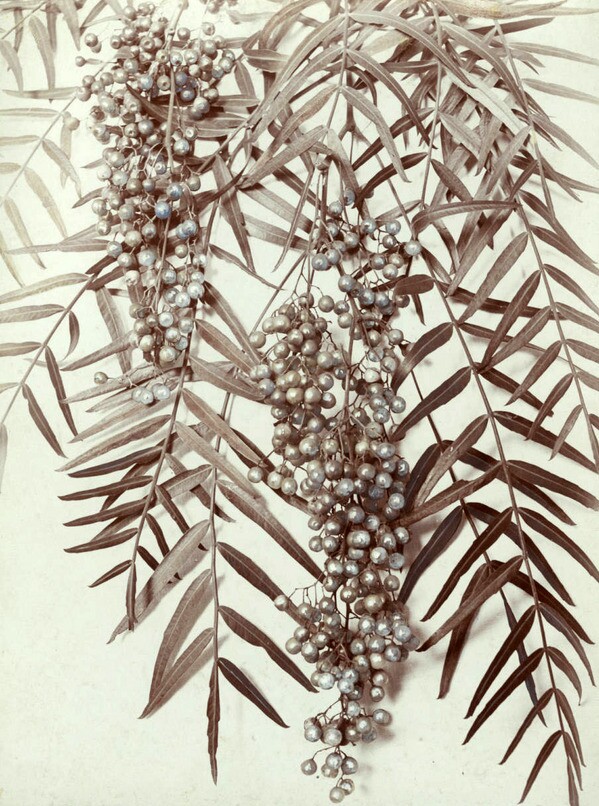

An import from South America's Andes mountain range, the Peruvian pepper tree (Schinus molle) is instantly recognizable for its fragrant, lacy leaves, drooping branches, and knotted trunk. It also produces bunches of small, pink berries that resemble peppercorns but are not the stuff of common table pepper; though they can be used sparingly as a seasoning, the berries are poisonous in large quantities. (The Peruvian pepper tree does have a cousin in the Brazilian pepper, or Schinus terebinthifolius, but neither is closely related to the true pepper plant, Piper nigrum.)

In its native Peru, indigenous South Americans found many practical uses for the tree, from firewood to medicinal applications. More than 1,000 years ago, brewers in the Wari Empire produced a spicy beer from the tree's berries. Much later, Spanish conquerors cleared entire forests of pepper trees for their timber, creating wagon wheels and posts from the wood.

But in California, the pepper tree has been planted almost exclusively for ornamental purposes.

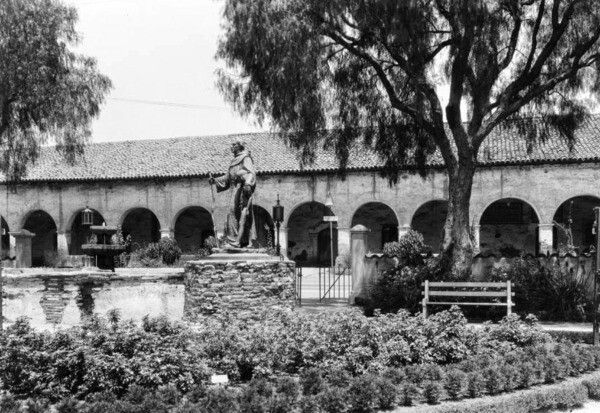

According to one popular telling, the tree first took root in California around 1825 at Mission San Luis Rey. After staying as a guest at the mission, a wandering sea captain repaid the padres' hospitality with a handful of seeds, or so the story goes. The head missionary, Father Antonio Peyri, later planted the seeds in the mission garden, where a massive, gnarled specimen still grows today. We can't know whether the tale is fact or just pure legend, but by the time Californians began investing their crumbling missions with mythic significance in the 1870s, the pepper tree had become as familiar a visual trope as the padres' sandals and staffs.

Soon, gardeners across the state planted pepper trees to lend a romantic aura to a site. One emerged from the ground outside Santa Barbara's city hall around 1880. At about the same time, another pepper tree took root next to the mission at San Juan Capistrano.

In other places, the pepper functioned as a general shade tree, planted more for its vaguely exotic appearance, tolerance of semiarid conditions, and ready availability than for its romantic associations. As early as 1858, Matthew Keller was growing 1,500 young pepper seedlings at his Los Angeles nursery. In 1861, merchant Juan Temple planted what may have been the city's first street trees, a row of peppers outside his Main Street shop.

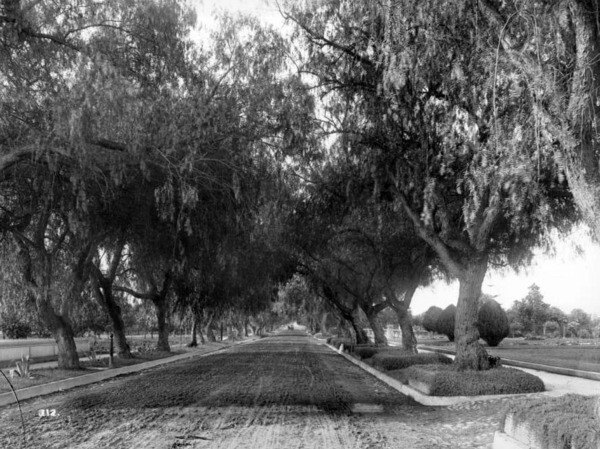

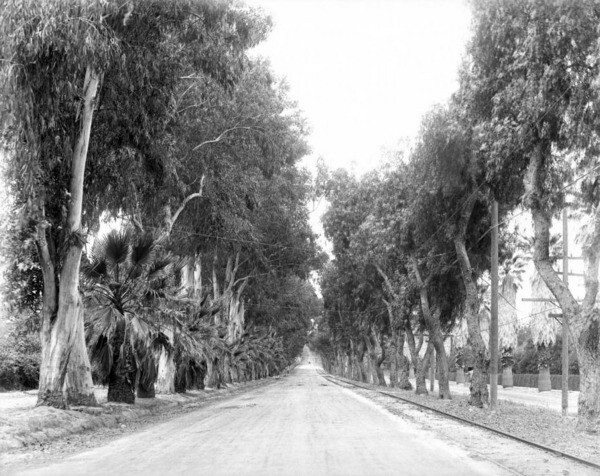

By the 1880s, pepper trees lined the signature thoroughfares of new communities across Southern California, from Ontario's Euclid Avenue to Riverside's Magnolia Avenue. (Town founder John W. North named the latter before discovering that southern magnolias cost $2 each. North opted instead to plant pepper and eucalyptus trees, priced at a more reasonable five cents each.) In Hollywood, subdivider Harvey H. Wilcox selected the pepper tree to shade his new town's roads. Pasadena boasted perhaps the most famous planting of pepper trees, whose spreading canopies created a much-photographed tunnel effect along Marengo Avenue.

But the dawn of the twentieth century introduced an existential threat to the pepper tree: a parasitic insect known as black scale. Though not fatal to pepper trees themselves, black scale jeopardized the health of the vast orange groves that carpeted much of Southern California. Faced with economic ruin, citrus growers -- joined by civic authorities -- declared war on the pepper tree.

But the familiar tree, prized for its beauty and nostalgic associations, had earned a loyal following. It often appeared on picture postcards and had become so associated with the state that many called it the California pepper tree, despite its South American origins. And so the campaign against the pepper tree did not go unchallenged. The Los Angeles Times published several reader-submitted poems praising the pepper tree and in a 1911 editorial cited its promotional value:

One of the first features to grip the eastern tourist when visiting this favored winter resort is the wonderful feathery foliage and the gorgeous scarlet berries of this matchless shade tree, giving, as it does, a pleasant air of holiday making and a wealth of tropical color to the Californian landscape...Why, the pepper tree has become an integral part of life in the sunny Southland...

Despite such passionate advocacy, the pepper tree soon lost its special place in the region's arboreal landscape. It fell out of favor as a street tree due to its tendency to heave sidewalks and send up suckers from its roots. And where black scale threatened citrus orchards, communities erased entire rows of peppers from their streets, in many cases replacing them with the upstart palms. Other reasons for their removal abounded. In 1913, the trees along Riverside's Magnolia Avenue fell to make way for new Pacific Electric Railway tracks. In 1931, highway widening claimed a row of historic pepper trees in Arcadia, planted nearly a half-century prior by Lucky Baldwin. And in 1955, a fungal infection forced Redlands to cut down its pepper trees. By then, the palm had already claimed the pepper's throne.