Why Is SoCal's Harbor Split Between Two Cities?

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

With the combined equivalent of 14 million standard shipping containers moving through San Pedro Bay's harbor each year, it's likely that many of the TVs, toys, and other imported goods sold at deep discount this Black Friday will have passed through the region's twin seaports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Now, as frenzied shoppers fight off the effects of tryptophan in their hunt for sales, explore the story of Southern California's unlikely harbor – and how it came to be divided between two cities – through selected images from the region's photographic archives.

San Francisco and San Diego both benefit from fine natural harbors, but topography forced Los Angeles to create its own; before improvements, the San Pedro Bay offered only partial shelter from winds and seas, and features like a sandbar in the middle of the bay and mudflats along the shore made the bay less than an ideal site for shipping.

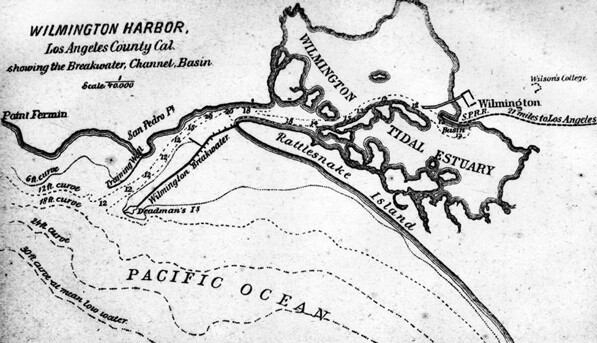

Supply ships anchored off San Pedro almost as soon as the Spanish colonized the region, but it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that Los Angeles began improving its ersatz harbor. To bolster his business transporting goods and passengers along the 21-mile route between Los Angeles and the San Pedro shoreline, teamster Phineas Banning dredged a channel through the bay's marshes and built a landing in the 1850s. Banning later doubled down on his investments, developing the harbor town of Wilmington and overseeing construction of the region's first railroad, the Los Angeles & San Pedro.

In the 1890s, Santa Monica – an even more unlikely place for a harbor – nearly replaced San Pedro as the region's major shipping port. In an attempt to cement its monopoly on trade through the region, the Southern Pacific Railroad built Port Los Angeles near the mouth of Santa Monica Canyon and lobbied the federal government to build a breakwater around its improvised harbor. The ploy backfired. Although the ensuing Free Harbor Fight lasted nearly a decade, Los Angeles' business leaders ultimately united to successfully win federal backing for an improved harbor in San Pedro Bay. The episode weakened the grip of the railroad – depicted in the popular press as a grasping Octopus – over the region's growing economy.

Although the victory of Harrison Gray Otis and others over the Southern Pacific ensured that ships would continue to steam into San Pedro Bay, the harbor's current configuration – two municipally owned seaports, one in Los Angeles and the other in Long Beach – was by no means fixed.

In 1906, four cities stretched tentacles of their own toward the harbor: Los Angeles, Long Beach, and the then-independent municipalities of Wilmington and San Pedro.

A series of legal and electoral contests ensued, as Steven P. Erie explains in his book "Globalizing L.A." Long Beach attempted to annex all of the strategically located Terminal Island; eventually, it won the island's eastern half. Los Angeles, meanwhile, sought to win control of the harbor by consolidating its own city government with that of the county's. When that stratagem failed, it annexed the long, narrow Shoestring Addition and turned to consolidation with Wilmington and San Pedro, which reluctantly merged with the metropolis in 1909.

Los Angeles' civic leaders then pressured Long Beach to follow suit, a move that prompted the city to consider seceding from Los Angeles County and becoming part of Orange County. Long Beach managed to maintain its independence without resorting to that drastic step, and it annexed more bayside land where it could develop a seaport of its own.

When the dust settled, Los Angeles and Long Beach shared control of the San Pedro Bay harbor. Both cities then granted their ports a significant degree of legal and political autonomy and proceeded to invest heavily in harbor improvements.

Building a harbor where nature did not provide one proved costly. Between 1910 and 1924, Los Angeles city voters approved $30 million in harbor bond measures. Long Beach initially lagged behind, but the discovery of oil in 1921 boosted the city's finances, and over a similar period Long Beach voters pledged $17 million toward their own municipal port.

Initially, domestic shipping dominated traffic at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, with timber from the Pacific Northwest sailing into the harbor and Southern California oil sailing out. Eventually, the opening of the Panama Canal and expanding global trade – as well as a the invention of post-Thanksgiving Day commercial extravaganzas – transformed the former mudflats of the San Pedro Bay into one of the busiest international shipping centers in the world.

This article was originally published on Nov. 23, 2012. It has been republished in conjunction with the broadcast of Lost LA's "Pacific Rim" epsiode.