Many Roads to the Historical Southland

Rugged mountains to the north, the vast Pacific Ocean to the west, and inhospitable desert to the east—natural barriers isolate Los Angeles from the rest of the continent on three sides. In an age before the transcontinental railroad and paved highways, not to mention air travel and the Internet, that inaccessibility presented a major challenge to the city's economic development.

Still, there were chinks in the barriers' armor. Ships could arrive by sea, of course, but mountain passes could also be traversed, and the deserts could be crossed by well-provisioned explorers. By the time California entered the Union in 1850, several routes, which come to life through the photographs and documents of Southern California's archives, provisionally connected Los Angeles to the rest of the state and the nation.

Perhaps the best known of these is El Camino Real (The Royal Highway), the road that transported Spanish missionaries as well as soldiers to the various settlements of Alta California. Pictured at the top of this post in a map from the UCLA Young Research Library's Special Collections, the road was present at California's very creation, as it roughly approximates the corridor used by the Spanish Governor Gaspar de Portolà, who from 1769 to 1770 led an expedition to settle San Diego and Monterey and protect Alta California from Russian and British colonization.

In its early days, Los Angeles was only a minor outpost of the Spanish empire, but its location along El Camino Real maintained the pueblo's connection to other settlements. To the south, the road passes through the Whittier Narrows by Mission San Gabriel Archangel, linking Los Angeles with the Presidio of San Diego and, further on, the missions of Baja California. To the north, the road crossed the Santa Monica Mountains at the Cahuenga Pass, pictured below, and continued on to San Francisco by way of Mission San Fernando.

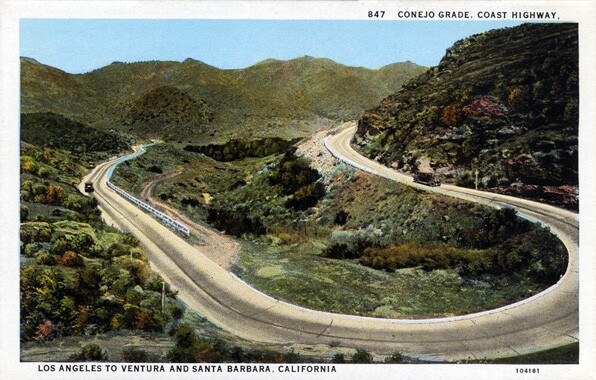

As El Camino Real connected many of California's most important cities, it was improved over the centuries to accommodate ox-carts, then stagecoaches, and finally was paved for automobile travel. In 1926, the route was designated U.S. Highway 101. Today, replica mission bells on the freeway's shoulder commemorate the path of the Franciscan friars.

Portola's trail linked Alta California's settlements with each other and to Baja California, but the province still lacked an overland route to the Spanish settlements of Mexico and New Mexico. That route was opened in 1774 by Juan Bautista de Anza, a soldier commissioned by the Viceroy of New Spain to reinforce the newly-settled province of Alta California. Crossing the Colorado River at Yuma, Anza's party trekked through the Sonoran Desert and discovered the first inland gateway to the Southern California coast: San Carlos Pass, which bisects the San Jacinto Mountains. Just three years later, 44 colonists known as Los Pobladores followed Anza's trail on their way to settling the new pueblo of Los Angeles.

Other overland routes were soon blazed as explorers found more suitable portals from the desert to coastal areas. Used for centuries by Native Americans, San Gorgonio Pass, pictured to the right in a postcard from the Pomona Public Library's Frasher Foto Postcard Collection, became the principal gateway between coastal California and the low deserts of Mexico, Arizona, and inland Southern California and today carries Interstate 10. Trapper Jedediah Smith used an old Mohave Indian trail to cross the San Bernardino Mountains on the way to Mission San Gabriel.

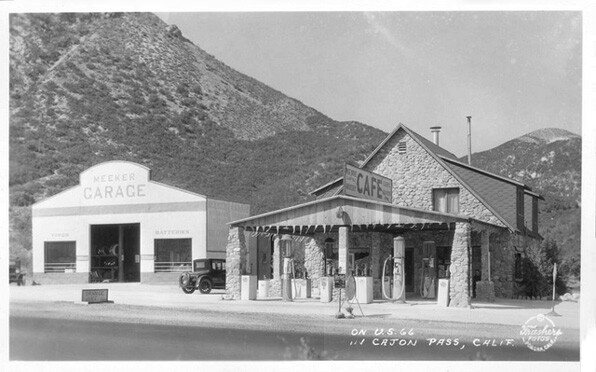

Later explorers would discover the usefulness of the Cajon Pass as a link between coastal Southern California and the Mojave Desert.

The pass, pictured to the left in a photo courtesy of the San Bernardino Public Library, separates the San Gabriel from the San Bernardino Mountains.

In 1829, traders opened a route between Los Angeles and Santa Fe via the Cajon Pass, providing a vital economic link between the two Mexican cities. The trade route was later used by the American adventurer John C. Frémont and his guide, Kit Carson, who named the corridor the Old Spanish Trail and advertised it as a link between the coast and the interior of the new American West. (The Old Spanish Trail Association's annual conference will be held in Pomona in June.)

Thus by the time California became a state in 1850, several overland routes carried trade, settlers, and communications between Los Angeles and the rest of the United States. Still, the journey could take half a year and was fraught with danger, and the voyage around Cape Horn or across the isthmus of Panama was no shorter or safer.

The completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 was a game-changer for Northern California, opening up San Francisco and the inland valleys of Sacramento and San Joaquin to more efficient transportation of goods and people. Southern California, however, still languished in its natural isolation.

That isolation ended when the Southern Pacific Railroad drove California's own "Golden Spike" into the soil of Soledad Canyon on September 5, 1876.

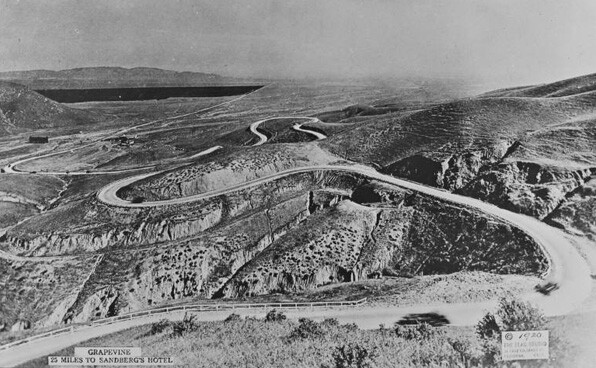

L.A.'s new railway link with San Francisco crossed the San Gabriel Mountains at the Newhall Pass. The portal was first crossed by a road to Fort Tejon in 1854 and was improved in 1863 when surveyor Edward Fitzgerald Beale cut a ninety-foot gap into mountain. Nicknamed Beale's Cut, the gap was almost immediately incorporated into the route of the Butterfield Overland Mail, a stagecoach that provided service between Los Angeles and points as distant as Saint Louis, Missouri. The Butterfield road continued north over the Tejon Pass, which Central Valley-bound motorists summit routinely on the stretch of I-5 known as the Grapevine.

That route was far too steep for trains, however. Instead, the Southern Pacific line climbed through Soledad Canyon into the Antelope Valley and then turned westward to enter the San Joaquin Valley via the Tehachapi Loop.

In the early twentieth century, as Southern Californians took to the road in their automobiles, highways began to integrate the Southland with the rest of the United States. Though modern engineering and the power of internal-combustion engines made more ambitious routes possible, most roads followed the same paths blazed by Indians and early Western explorers.

The storied Route 66, for example, entered coastal Southern California via the Cajon Pass. Built in the 1920s, U.S. Highway 66 is perhaps the nation's best-remembered highway, linking countless cities and small towns along a sprawling route from Chicago to the Pacific Ocean. Though decommissioned in 1985, the highway lives on in the archives of the Autry National Center's Autry Library, a founding member of the Route 66 Archives and Research Collaboration.