From Mockery To Meaning: Asian Surnames Defined

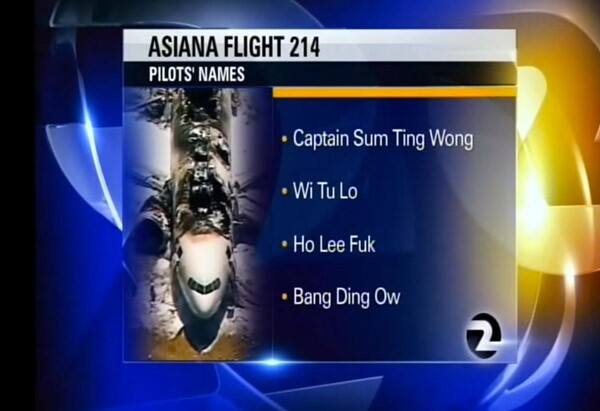

An on-air prank on a TV news station mocked the Asian names of the supposed crew of July's Asiana Airlines crash. | Photo: KTVU

Following last month's crash landing of Asiana Airlines Flight 214 at San Francisco International Airport, which killed three people and injured 181, insult was, quite literally, added to injury when a San Francisco TV news anchor reported what was supposedly the names of the fateful flight's crew.

The result turned out to be an obvious juvenile prank that employed phonetic puns mocking Asian-sounding names: the fictional "Captain Sum Ting Wong" was one of them.

And indeed there was something wrong: the incident raised the ire of the station's Asian viewership, as well as the Asian American community nationwide, and despite an apology from the station, the Korean-based air carrier even threatened to sue on grounds of defamation. Eventually, three producers were fired from the station in late July and the lawsuit was dropped.

Though Asian Americans aren't totally above making up phonetic pun jokes of our own (Potential names for pho restaurants are a popular subject -- pho realz), actual names of Asian origin, particularly family names, are much more than just random monosyllabic noises -- they have actual meanings. These names are not only expressions of ethnic and cultural pride, but familial heritage and history, sometimes representing a lineage that dates back for centuries.

With Asia being a continent made up of several countries, there are no "Asian surnames" per se, and in fact, particular surnames are usually a key to identifying one's particular ethnicity or national origin -- names like "Kim" and "Park" are common family names in Korea, while "Nguyen" and "Tran" are common in Vietnam, for instance.

China, in all of its historic iterations, has been the dominant cultural influence in the whole of Asia, and to this day there are sizable, and influential, ethnic Chinese communities in every Asian nation. Variants of Chinese family names can be found in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, The Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, as well as the global Chinese diaspora.

Chinese American surnames also reveal clues as to immigration and regional origin. Most Chinese Americans have Cantonese roots, as the first wave of Chinese immigration consisted of workers from the Guangdong province arriving in California around 1820. The Chinatowns of Los Angeles and San Francisco were built by Cantonese-speaking Chinese. Many of them bore Cantonese forms of Chinese family names, phonetically translated into Roman letters, thus using names such as Chan (a form of "Chen," a reference to a region in ancient China), Lee (a form of "Li," meaning "plum tree"), and Wong (a form of either "Wang," meaning "king," or "Huang," meaning "yellow"). More recent Chinese immigrants are Mandarin-speaking, using family names corresponding to that language.

In Korea, family names were not used until around the 5th century when the upper classes began adopting Chinese-based family names. Of some 80 million Koreans worldwide, there are only about 300 known Korean family names, the most popular being Kim (meaning "gold"), Lee, and Park (meaning "magnolia tree"). Other names include Choi ("pinnacle") and Moon ("wisdom").

Many common Japanese surnames are compound phrases based on references to geography or nature, and historically point to a family's place of origin. The surname Fujimoto, for example, means "base of Mt. Fuji." Nakamura means "central village." One only needs to learn a small number of Japanese words in order to interpret the etymology of most Japanese family names.

Like many Asian cultures, Vietnamese, in the context of their native language, applies the family name first. In Vietnam, names consist of the family name, a middle name and their given name, in that order, which is reversed in Western language usage. The ubiquitous Vietnamese family name of Nguyen means "original" or "first."

Nearly 400 years of Spanish colonization have resulted in a majority of Filipino surnames to be Hispanic in origin (and because of the Western influence, the family name is the last name). Most Filipino Spanish surnames are derived from family names of Basque Spanish nobility (Mendoza, Garcia, Hernandez) and Catholicism (De La Cruz, Santos, my own surname included). But a number of Filipino surnames are also Chinese in origin, specifically from nearby southern China. Family names such as Ang, Tan, and Yap are distinctly Chinese Filipino, same with compound Hispanicized Chinese surnames such as Cojuangco or Yupangco. There are also indigenous Philippine surnames like Batongmalaque or Tayag, many of which survived due to having lineage to tribal royalty.

Up until 100 years ago, people in Thailand were known by one name. After 1913, Thais and new Immigrants to the country had to adopt a unique family surname (following the Western form of family name last), which usually translates into a phrase that represents a positive virtue. The unique surname ensures that everyone who shares that name is related, and despite the apparent lengthiness of many Thai names when translated into Roman letters, new Thai family surnames are not allowed to exceed 10 Thai letters in length -- it is only due to the phonetic translation of Thai letters into Roman syllables that make the surnames appear long. Of course, indigenous Thais picked the shorter names.

In Asian countries with large Muslim populations such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, Arabic names like Mohammed or Abdullah are commonly employed as first or last names. And in India, home to over two dozen major language groups, surnames come in different shapes and sizes.

As someone who grew up going to school in a multicultural environment, where even the Asian students represented diverse ethnicities, what bothered me most about the Asiana Airlines prank, aside from the too-soon factor of poking fun at a catastrophe where people died and sustained serious injuries, was the application of mock-Chinese puns towards a flight crew that was, in actuality, Korean. It insinuated that "All Asians are the same," when, despite a few commonalities, we really aren't. Jokes and humor, even edgy humor, are fine. But can't they be more witty and intellectual than merely ignorant?