American Sons & Daughters: Mixed Race, Identity in Southern California

This is how we began. I looked out at the 300 faces before me and said, "How many of you in this classroom are often asked, in a bar or a store or at a party, What are you?" Maybe a hundred young people raised their hands, and they couldn't believe that's what we would spend ten weeks talking about.

"People will guess, all the time, and they're never right," one young woman said.

"People think I'm black because of my hair. But I'm Ashkenazi Jewish," a young man said.

"People think I'm Asian because of my eyes," someone else said.

"My son is really light, because he's Mexican-Irish," said Arely, who is Mexican-American, standing in front of the class and showing her children from a cell phone photo onto the screens. "But my daughter is darker, since she's Mexican-Colombian, and everyone talks about that. I already know how hard that's going to be for her."

The class is "The Mixed Race Novel and the American Experience." But of course we didn't talk only about books -- we talked about who we are, how America sees us, how our families see us, and most importantly, how we see ourselves. We talked about America's ongoing obsession with hair and melanin, about what it means to be undocumented, what it means to be a mother, what it means to witness a murder or to lose a dog. But all those discussions began with what it means to be of mixed racial and cultural heritage, and many students in this class at UC Riverside say this was their first time ever talking about these very personal things in an open forum.

We began with pictures of my family and my high school, just down the street from the university campus. That's because when a short blonde woman whose heritage seems pale as possible begins a discussion of what it feels like to be biracial, it's best to start with my three girls, whose faces are varying shades of copper and almond and freckles and gold, and their father, who is massive and brown-skinned. "How would you identify this person?" I asked the class, with a huge photo of him in a suit. "He's black," the class responded. "Now look at the rest of his family," I said, showing the range of skin tones and hair in the Sims family. "I guess everyone is mixed, then," someone said, and we were launched into extraordinary conversations.

The four novels: "Wingshooters" by Nina Revoyr, about a young girl who is half-Japanese and half-Wisconsin; "American Son" by Brian Ascalon Roley, about a young man who is half-Filipino and half-military-American; "The Girl Who Fell From the Sky" by Heidi Durrow, about a young girl who is half-Danish and half-African American (also military); and my novel "Highwire Moon" about a girl who is half-Oaxacan-Mixtec-Mexican and half-Coloradan. But while we talked about the characters and the sentences and the plots, the students talked about their own lives.

Continents and nations. How reductive is it to assume someone is "Latin American" or "Asian" when those are not monolithic places? In this one room were students whose parents are from Jalisco and Guerrero and Sinaloa and Mexico City, from Panama and Nicaragua and El Salvador and Paraguay, who might not even eat the same foods or speak the same languages. In this one room were students whose parents are from Indonesia and the Philippines and Taiwan and Shanghai, Vietnam and Laos and Cambodia and Japan, for which that is also true. Students who are "African-American" might have parents from Mississippi, Compton, Eritrea, or Nigeria. What if your city defines you, or your very small town, where there are more horses than people?

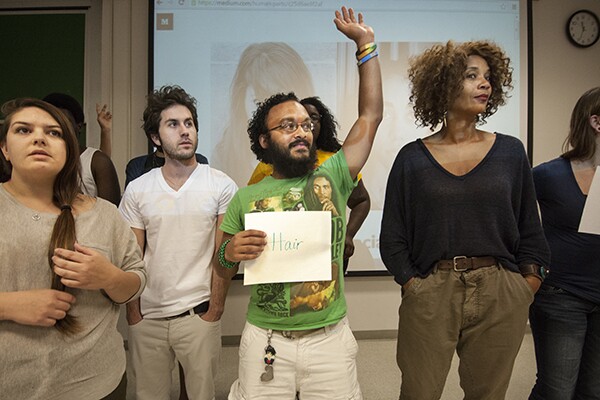

One day I handed out nine signs. I asked three questions: How do others identify you? How does your family identify you? And most importantly, how do you identify yourself? Students streamed down the aisles to the front and stood behind the words: Physical Features, Hair, Religion, Art or Music, City or Neighborhood, Family, Job, Parenthood, and Sport.

Megan was first. She said, "Everyone sees my chair. That's how they define me." It was the perfect way to begin.

Kaliah, who has braids and amber skin and almond eyes, said "My family knows me as the ditsy blonde," (and I forgave her).

Bria said, "I'm tall so everyone thinks I should play basketball or volleyball. But my family knows me as the good girl."

Marquis said, "Everyone assumes I'm a ladies' man." The class laughed, and one girl said, "Because you are!" Then he said, "But I see myself as a faithful partner -- to my boyfriend." Roars and clapping.

Michael and Will talked about people's obsessions with their hair, about how total strangers will bury their fingers in natural Afros or ask about the cleanliness of dreadlocks. Merima talked about her hijab, about being Bosnian and Turkish and a refugee. Dominique talked about how her Dining Services shirt leads people to identify her as an employee, and Ivan Copado talked about his day job at the Agua Mansa landfill, where his name is written so small on his nametag that people squint and call him "Juan." James held up his skateboard and said, "This is who I am."

Identity. Parenting. What is the difference between being multi-racial and multi-cultural? Melanin. Hair. Lips. Noses. Eyes. We spoke often of the words immutable and continent. Some characteristics can never be changed. Sometimes hair is covered by a veil, or shaved, but it still exists. How is hair good or bad?

O, Hair! The collection of dead keratin cells which was biologically meant to protect the scalp and skull from extremes of heat and cold, which is decorated and shorn and straightened and curled, which still engenders the most extreme reactions of those who think their hair is the cultural norm. Regina Louise, one of the teaching assistants, described how "my grandmother trapped me between her massive thighs and ran that hot comb through my hair til you could smell it burning." We talked about the kitchen -- where hair is the most tangled.

O, Melanin! Durrow's book led the class to learn the term ashy, which Jerome patiently explained: "White people are ashy, too. You just can't see it. It means dry skin. Elbows and hands and legs." We talked about lotion.

O, Lips and Eyes and Noses! Their thickness, or thinness, their slant and shade, nostrils and cartilage.

Then, in November, Richard Cohen wrote in a Washington Post editorial: "People with conventional views must repress a gag reflex when considering the mayor-elect of New York -- a white man married to a black woman and with two biracial children ... This family represents the cultural changes that have enveloped parts -- but not all -- of America. To cultural conservatives, this doesn't look like their country at all."

Here in Riverside, we laughed pretty hard. Mr. Cohen's "conventional" people, whoever they are, would be straight-up choking in much of Southern California, in our classrooms, on our streets, in our restaurants, and I'm assuming they'd be close to unconscious in my house, with my children and relatives.

But here's something for those who think this doesn't look like "their country at all" -- we have numbers, and words, and this autumn, we have had a lot of fun talking about hair and stories and words like immutable and ashy, words like naranja and balikbayan. We watched the 626 music video about the San Gabriel Valley, which made us all hungry for noodles. Here we are -- identifying ourselves. Today, Arely, who showed us cell phone photos of her children that first week, told me that people often think her daughter is Persian -- so she's joined her school's Persian club. It doesn't get better than that.