How the Tuskegee Airmen Rose Above Racism

Relive the excitement of man’s first steps on the moon and the long journey it took to get there with 20 new hours of out of this world programming on KCET's “Summer of Space" Watch out for “American Experience: Chasing the Moon” and a KCET-exclusive first look at "Blue Sky Metropolis," four one-hour episodes that examine Southern California’s role in the history of aviation and aerospace.

They rose from adversity, through Competence, Courage, Commitment and Capacity to serve America on Silver Wings and to set a standard few will transcend.

This message is inscribed beneath the Tuskegee Airmen statue at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado. These words speak to the dedication of all who had a hand in the hard-fought success of the Tuskegee Airmen.

The Beginning of the Tuskegee Airmen

At the height of a tumultuous time in history, men stepped forward to serve in WWII. Black men had served in the military before WWII but had not been allowed to become pilots. Desperately needing pilots, the U.S. government-sponsored the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Partnering with over a thousand colleges and flight schools, the government paid for the ground and flight school instruction while the colleges provided the instructors. The goal was to turn 20,000 college students into pilots, but black men were not considered at first.

Even though black men served as pilots for France in WWl, the pervasive thought at that time was that these men were incapable of handling bombers or fighter planes. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), churches and newspaper articles all pressured the government to accept all men into the military in whatever role they were qualified to perform. This pressure led to a separate flight school program in Tuskegee, Alabama for black men interested in becoming pilots.

Training at Tuskegee

While the government did succumb to pressure, allowing the men to go through the training, most people considered the program an "experiment" and expected the men to fail. Few considered black men intelligent or capable enough to become pilots. Unfortunately, these views were held by a majority of military leaders who cited a biased 1925 U.S. Army War College study that stated, “Blacks are mentally inferior, by nature subservient and cowards in the face of danger. They are unfit for combat.” President Roosevelt issued the Selective Training and Service Act in 1940, which included a bill that “ended discrimination” in the army, but not segregation.

Rising above prejudice and racism, these exceptional men set out to prove themselves. Most of them had already attained a college degree and were well prepared to take on the challenge. The coursework was provided by the Tuskegee Institute, while the flight training was provided by private flight schools. Primary, basic and advanced flying training was scheduled to last one year. Upon passing this training, graduates would enter the U.S. Army Air Corps to be trained on military aircraft and become fighter pilots and bombardiers.

The Tuskegee Institute was chosen because the surrounding flight schools had a history of preparing civilian pilots, and the southern location allowed for year-round flying. Possibly more important to the decision-makers of the day was the fact that the local population was already segregated. Even though the coursework and flight training were identical for all potential pilots, the government support for the program was dependent on maintaining segregation. The Tuskegee Institute was also responsible for training support personnel: navigators, mechanics, cooks, nurses, crew chiefs and others, who would be needed to support the additional fighter pilots and maintain the aircraft. The entire group, pilots and support personnel, became known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

The Tuskegee Airmen Pilot Program graduated its first five candidates in the spring of 1942. Twelve men enrolled in that historic first class, but not all graduated. The first to receive the silver wings indicative of a pilot after completing their training were Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., Lemuel R. Custis, Charles DeBow, George S. Roberts and Mac Ross.

Proving Themselves in Combat

Initial assignments were in North Africa and Morocco, then Sicily and Italy. The 99th squadron, flying P40 Warhawk aircraft, was the first squadron to have mostly black pilots. Led by Lt. Colonel Benjamin Davis Jr., from the first Tuskegee graduating class, the 99th teamed up with three other squadrons to form the 332nd fighter group in July 1944. This fighter group earned a name for themselves by supporting U.S. ground forces, attacking enemy installation, successfully engaging the enemy in air combat and providing bomber escort missions for the Fifteenth Air Forces. Before these escorts, the U.S. was losing twelve bombers a day. The Tuskegee Airmen are credited with cutting these losses drastically, only losing bombers on five of the 205 escort missions. Some say the Tuskegee Airmen never lost a bomber, but that myth began because no other escort group could claim such low losses.

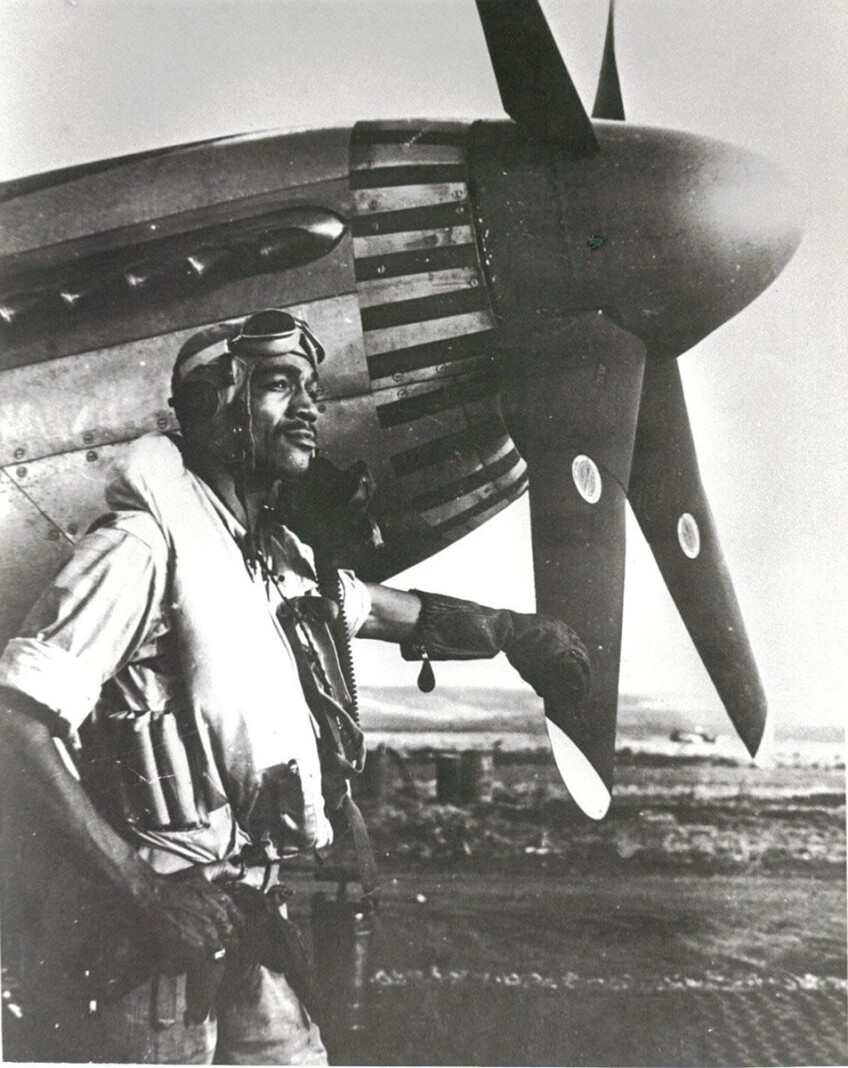

Their successful work as escorts earned them the name of Red-Tailed Angels. To distinguish their planes from the others, they painted the tail surfaces of all their aircraft red. Also known as Red Tails, the Tuskegee Airmen are most commonly associated with red-tailed Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and North American P-51 Mustangs. The P-51B and D Mustangs also had yellow wing bands and red propeller spinners. The P51s had red nose-bands and red rudders.

From 1942 to 1946, a total of 996 Army Air Corps pilots, 20 bomber pilots and 16,000 ground personnel graduated from Tuskegee. These forces flew over 15,000 missions and earned more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses. In part due to the Tuskegee Airmen proving themselves in battle, President Truman ended segregation in the military with an executive order in 1948. This opened up opportunities for these experienced pilots to join the newly formed Air Force and continue their service.

Contributions

Despite the expectation of failure, the Tuskegee Airmen proved themselves capable of excelling in the military and serving with distinction. Col. Davis Jr. not only led his fellow airmen to many victories in WWll, but he also became the first African American general in the U.S. Air Force. Col. Charles E. McGee holds the record for the most combat missions flown in three wars. Buford Johnson was one of the first African American master mechanics in the U.S. Army Air Corps. The first black man to command a racially integrated U.S. Air Force Unit was George "Spanky" Roberts, who retired from the Air Force as a full colonel. Lt. Col. Ted Lumpkin, Jr. was selected to attend officer training after graduating with radar training from Tuskegee. He continued his education at the University of Southern California.

Many of the Tuskegee Airmen continued to blaze a path in aviation, enabling others to follow. Lt. Col. Robert Friend served in both Vietnam and Korea during his twenty-eight years in the Air Force. He also worked on space launch vehicles and formed an aerospace company. Edward A. Gibbs founded Negro Airmen International after he served as a civilian flight instructor in the U.S. Aviation Cadet Program. Clarence Huntley Jr. served in the Korean War then worked as a skycap at the Los Angeles International and Burbank Airports. Marion Rodgers worked in communications at North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), then served as a program developer for the Apollo 13 project.

After paving the way toward equality, their legacy persists, encouraging others to continue that battle for equality today. The first black woman Air Force pilot, Teresa Claiborne, drew inspiration from the Tuskegee Airmen saying, “They made me know all things were possible.” President George W. Bush awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the airmen in 2007 in recognition for valor in action against the enemy.

The Tuskegee Airmen fought through ignorance and prejudice to have distinguished military and civilian careers, proving to every skeptic that excellence is not a matter of color or race, but the result of commitment and determination. On the shoulders of these incredible men and women, many more will rise above preconceived notions to inspire those yet to come.

Top Image: Lt. Dempsey W. Morgan Jr., Lt. Carroll S. Woods, Lt. Robert H. Nelson Jr., Capt. Andrew D. Turner and Lt. Clarence P. Lester in the shadow of a P-51 Mustang in Italy. August 1944. | Courtesy of the National Archives and U.S. Air Force