Creating the Santa Monica Freeway

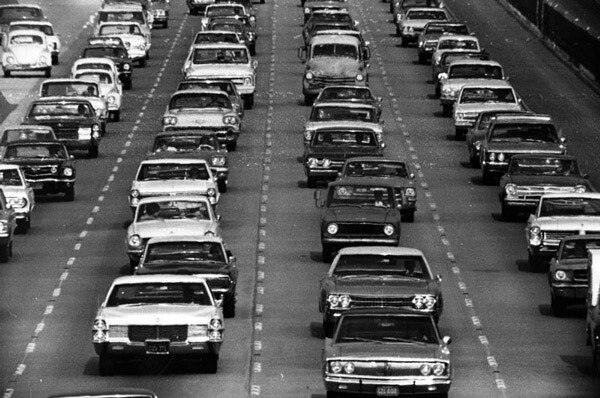

Today, the Santa Monica (I-10) Freeway is an indelible marker across the Los Angeles landscape, a mini-equator that delineates boundaries between cultural and historical hemispheres of the city. Southern Californians depend on the freeway as a vital link between the Westside and downtown Los Angeles and as a transcontinental connection to points east. But in the 1940s, '50s, and '60s, the I-10 was part of a massive public works project to bind the nation with concrete superhighways, then perceived as a threat that united local communities and later -- according to one admirer -- as a work of art.

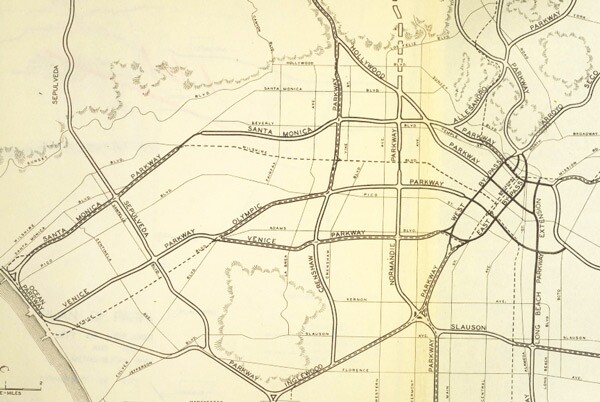

Although transportation planners envisioned its general path to the sea as early as the 1940s, the Santa Monica Freeway is best understood as a member of Southern California's second generation of limited-access highways. Unlike L.A.'s first freeways, their routes mapped by local planners and their construction financed by municipal and state funds, these second-generation freeways were part of a broader statewide and national effort.

Many were part of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highway, which in Southern California included the Santa Ana (I-5), San Diego (I-405), and Santa Monica (I-10). Under the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956, the federal government would provide 90 percent of the funding for these new freeways that extended across the continent.

Greater state funding came in 1959 with the establishment of the California Freeway and Expressway System, which incorporated early, sporadic efforts at freeway building into a coherent statewide map of urban and rural superhighways.

With this backing came bolder plans and a tendency to subordinate local concerns to the needs of the larger region. Mapping their proposed routes, planners drew lines straight through established residential communities. Houses and local businesses along the route were no more an obstacle than existing surface streets or water mains; the state would purchase whatever property it needed, relocate residents, and reconfigure the neighborhoods around the new freeway.

It's little surprise, then, that local opposition immediately coalesced against the Santa Monica Freeway when state highway planners announced a major part of its route in August 1955. The entire route – known originally as the Olympic Freeway – would span 16.6 miles between the East L.A. Interchange in Boyle Heights and Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica, barreling through quiet bedroom communities on its path to the sea.

Hundreds of churches, homeowners groups, and other community organizations rallied against the proposal, focusing their opposition on the 6.6-mile stretch west of La Cienega Boulevard.

Channeling the ire of his West L.A. constituents, State Assembly Member Thomas Rees declared at a public hearing that the proposed freeway "would constitute a wall diagonally across this area," adding that it would pass menacingly close to several schoolyards. Others raised concerns about air pollution, while Superior Court Judge Stanley Mosk spoke on behalf of a local orphanage over which he presided, warning that the freeway would disrupt the lives of 200 orphans.

Still, the general consensus held that Los Angeles needed a freeway connecting downtown to the coast. Instead of attacking the idea itself, opponents limited their criticism to the freeway's route, advancing alternatives that would steer the freeway clear of their homes. Many, for instance, argued for a viaduct freeway atop Venice Boulevard, whose commodious median had been unused since the Pacific Electric decommissioned its Venice Short Line in 1950.

Although planners rejected the Venice proposal, in April 1956 they did revise their original route in the face of community opposition. But while the new route saved 47 homes, it largely shifted the freeway away from the domains of its most vocal opponents and into new neighborhoods. Local opposition persisted, but the highway commission held firm.

On June 17, 1957, construction crews broke ground on the first segment of the newly renamed Santa Monica Freeway over the Los Angeles River. Land acquisition for the freeway's right-of-way began in 1958, and by 1961 families – living in houses the state had purchased and then rented back to their occupants – received orders to move.

On December 4, 1961, Governor Edmund "Pat" Brown dedicated the first, easternmost segment of the freeway as crews began work on the route's West Los Angeles and Santa Monica portions. At its western extreme, the freeway required a 7,000-foot-long, 20-foot-deep cut before reaching the Pacific Coast Highway's McClure Tunnel.

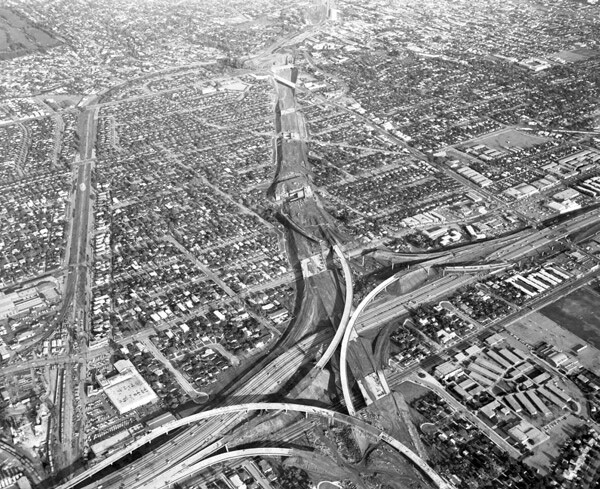

Perhaps the most ambitious part of the project was the route's interchange with the San Diego (I-405) Freeway. Designed by Marilyn Reece, the first woman to serve as an associate highway engineer for the state, the interchange cost an estimated $20 million to build. With the aid of an early computer program, Reece plotted the curves of its ramps and soaring, 75-foot-tall bridges to allow automobiles to transition between freeways at 55 miles per hour – a significant speed increase over the tolerance of earlier interchanges, like downtown's Four Level, which required cars to slow to 35 miles per hour.

Later, in his 1971 book "Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies," architectural historian Reyner Banham singled out Reece's interchange for praise:

...[T]he wide-swinging curved ramps of the intersection of the Santa Monica and the San Diego freeways, which immediately persuaded me that the Los Angeles freeway system is indeed one of the greater works of Man, must be among the younger monuments of the system. It is more customary to praise the famous four-level intersection...but its virtues seem to me little more than statistical whereas the Santa Monica/San Diego intersection is a work of art, both as a pattern on the map, as a monument against the sky, and as a kinetic experience as one sweeps through it.

Work on the freeway progressed slowly, and in stages. It was not until October 1964 that it extended west to La Cienega Boulevard, and on January 29, 1965 – several years after residents in the freeway's path were displaced – a Goodyear blimp helped cut the ribbon on the 4.5-mile segment between La Cienega and Bundy Drive. By then, local opposition had dissipated, and civic groups participated in the dedication festivities. The final segment through Santa Monica opened on January 5, 1966.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, cultural institutions, and private collectors. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.