The Rise and Fall of Henry "Don Enrique" Dalton, the British Ranchero of the San Gabriel Valley

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, a large chunk of what is now part of the United States became part of the newly sovereign nation. Alta California, which included areas of present day California and Arizona, and portions of Nevada and Utah, was now Mexican territory -- not yet considered a state due to its small population.

By this time the Mission system, established decades prior by Spanish settlers, was slowly unraveling. The indigenous population, forced to live on Mission grounds, suffered from European diseases, resulting in the catastrophic decline of its population, from around 65,000 in 1770, to only 17,000 by 1830.

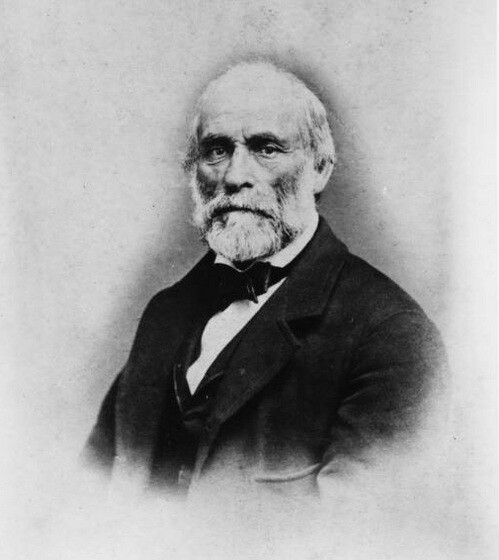

As described by explorer and tradesman Richard Henry Dana in his classic "Two Years Before The Mast," published in 1840, Alta California at this time, under Mexican rule, was brimming with trade through its ports all along the coast. One of the most important trade cities in the world that shipped to these flourishing ports was the Peruvian port of Callao, where a London-born business man named Henry Dalton was beginning to make his mark in the world. Using capital he had earned from gambling, he quickly set up his own trading company -- Enrique Dalton & Co. -- co-opting a more familiar name (to locals) that would stick with the young Englishman for the rest of his life.

After two decades of trade based in Peru, Dalton had had enough. With his fortunes in flux, and health declining, he began to think of ways to expand his business, while starting life anew. While Dalton may have familiarized himself with the Californias from his trade routes along the west coast of the Americas, it was perhaps the work of Alexander Forbes, a Scotch merchant based in Tepic, Mexico who published the first English-language book on California, "California: A History of Upper and Lower California," in 1839, that opened up his mind to the still-untapped resources of the soon-to-be Golden State.

Journey to the West

Dalton arrived in Los Angeles in 1843, as he guided the Mexican brig "Soledad," from Mazatlan to San Pedro. Seeing the potential for hides, tallow, and land, not to mention the growing gold fever in the San Gabriel Mountains, Dalton decided to start a new life in the still nascent city, its population still in the low thousands.

The first of Dalton's many land purchases was made as soon as he landed ashore. A plot of land bordered by Main, Spring, and Court Streets, in what is now downtown L.A., was sold to Dalton by Rafael Guirado, father-in-law of future-governor John G. Downey. There he built an adobe retail store, where he sold the merchandise arriving for him in San Pedro (and later, products from his ranchos), often in exchange for goods supplied by local rancheros. As one of the main retailers in the Pueblo, he became acquainted with many of the prominent figures of early Los Angeles, such as John Temple, Luis Vignes, Pio Pico, and Luis Arenas. Dalton would continue to manage this store until 1860.

On the same lot, he built one of the first wooden residences in the Pueblo, described by C.C. Baker, author of "Don Enrique Dalton of the Azusa," as "one and a half stories high ... one of the pretentious buildings of the town." Later he would build the first two-story brick residence in the Pueblo, on the site where St. Vibiana's Catheral was eventually built, and still stands today.

Into the Valley

In August, 1844, a new California law forbade the sale of any land by an individual, which put a heavy damper on Dalton's desire to expand his land holdings. But, as luck would have it, the growing political unrest within California proved to be beneficial for Dalton, who, after an unexpected turn of events, was able to circumvent the rules to continue his ascent of his empire.

When unpopular Governor Micheltorena was warned of a planned rebellion led by former Governors Jose Castro and Juan Bautista Alvarado in a power struggle between the Mexican government and the Californios, he initially conceded by signing the Treaty of Santa Teresa, in which he agreed to send his unruly troops back to Mexico. Micheltorena, however, was not ready to give up just yet. In an effort to retaliate against the rebellion, Micheltorena enlisted the help of Pio Pico and Jose Carillo to build up a force of his own; there was one problem, however: there was no money to spend on such a force.

With a bit of bending of their own rules, they came up with a solution. They were owed $1,000 by Luis Arenas, a ranchero who owned a large swath of land surrounding the San Gabriel River. The only way he could pay back the large sum was to sell his land -- which the August 1844 law prevented him from doing. So Micheltorena quickly granted special authorization to Pico and Carillo to allow the sale of Arenas' land, stating that it was "the only means we depend upon in order to equip the number of men now ready to enlist under the aforesaid chief."

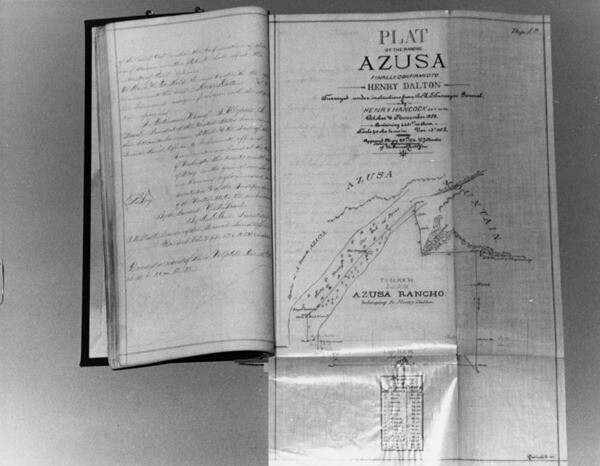

The buyer of Arenas' land was none other than Henry Dalton, who bought himself a quite large gift on Christmas Eve, 1844: one-third of Rancho San Jose, which included present day Claremont, Pomona, Laverne, and San Dimas; and all of Rancho El Susa, now named Rancho Azusa de Dalton, its named derived from the Asuksa-nga, the indigenous people that previously occupied the land. The purchase of the ranch, which covered present day Azusa, Arcadia, Monrovia, Irwindale, and Baldwin Park, included "cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, and other animals worth $3000, vineyard with 7000 growing vines worth $1500; plus an irrigation dam on the Azusa River, a ditch to the vineyard, and an abundance of water except in late summer of dry years," as recounted in "The Life and Times of Henry Dalton and the Rancho Azusa" by Sheldon Jackson.

The following year, Dalton acquired Rancho San Francisquito in a Mexican land grant given by Governor Pio Pico. This included present day cities of El Monte, Irwindale, and Temple City. In 1847, Dalton purchased Rancho Santa Anita from Scottish-born, Mexican citizen Hugo Reid, adding 13,300 acres to his rapidly expanding land portfolio. This ranch included all or portions of present day cities of Arcadia, Monrovia, Sierra Madre, Pasadena and San Marino.

Within three years of his arrival in Los Angeles, Dalton became one of the biggest landowners in the city, with almost the entire foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains in his hands.

"The Most Beautiful Girl in Los Angeles"

By 1847 the Mexican American war had entered its second year, and Dalton had already lost $6160 worth of goods to American troops at the harbor in San Pedro. The Californios by this time had become exhausted and in desperate need for supplies; Dalton showed his support for the Californios by providing more than $30,000 worth of supplies and cash -- which the Mexican government promised to return with 100% interest.

Some questioned why Dalton gave up so much to the Californios' cause, since it seemed unlikely that he would be paid back by the losing Mexican government. But for others, it was simple: he had fallen for a woman, who happened to be the sister-in-law of Jose Maria Flores, an officer in the Mexican army who commandeered the Californios. Maria Guadalupe Zamorano was one of the many Californian beauties wooed at the time by the over-eager Anglo bachelors. At the first Independence Day celebration in the city of Los Angeles, held July 1847, young Guadalupe was awarded the a prize for being the top beauty at the ball. The prize was presented by visiting New York Volunteers officer John M. Hollingsworth, a "connoisseur of women" who had a thing for California girls; he wrote in his diary about an encounter at a party: "Saw a beautiful Spanish girl there, gave her a bouquet, and murdered Spanish at her at a great rate."

Dalton, a grizzled but wealthy 43 year old, somehow won the heart of 14 year-old Guadalupe, who at the time was considered "the most beautiful girl in Los Angeles." Dalton was baptized at Mission San Gabriel in order to be allowed to marry the Californian girl.

Meanwhile the ravaging war carried on, and continued to drain Dalton's wealth. After the Americans captured Los Angeles, their troops broke into Dalton's town home and ransacked his wine cellar, cut down his fence for firewood, and smashed his dinnerware. Further, his declining fortune was accelerated by his lavish spending toward his new wife: his account book recorded his purchases of "July 31, 1847, $500, sundry expenses in marriage; November 30, 1847, $626, silks, fine clothing, etc."

In the end, after America's victory over the Californios, Dalton failed to collect a single dollar for his losses and investment from the Mexican government.

Squatter's Rights

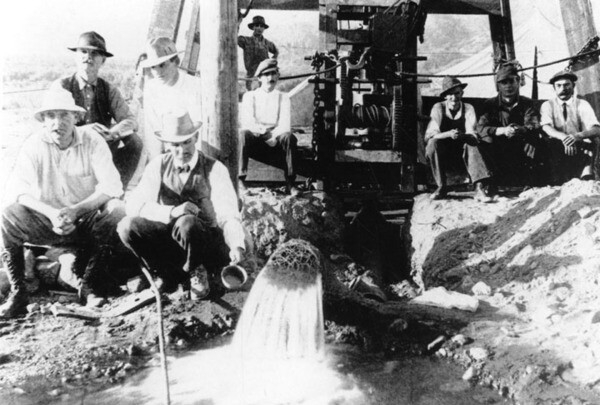

While the war devastated his fortunes, Dalton still had his land holdings, and was now determined to make it as a ranchero. But what he thought to be an asset at his Rancho -- a water system that Luis Arenas had begun to build -- would eventually lead to the loss of much of his wealth.

Arenas had constructed an irrigation system that carried water down to the Rancho from the San Gabriel Mountains via the Azusa River (San Gabriel River). Dalton, soon after acquiring the property, doubled the capacity of the irrigation ditch, to 1,800 gallons a minute. In 1854, he built a flour mill that was run by the force of the water flowing through the ditch -- this is believed to be the earliest water power development in Southern California.

Using the mill as a selling point, Dalton attempted to subdivide underutilized parts of the Rancho. He devised an unusual ownership arrangement that offered shares in place of actual land, with a raffle that promised prizes such as the "most magnificent private dwellings in southern California," and one of the many vineyards that he owned. Included in the campaign was a plan for Benton City, which would have contained "some of the richest and most fertile lands in the world." Out of 84,000 shares made available, only 166 were sold. The campaign was ended abruptly.

Meanwhile, Dalton and other rancheros struggled to keep squatters off of their land. Henry Hancock's survey of the Rancho Azusa in 1858 (as required by the new American government) was seen by Dalton as erroneous, as he felt that it cheated him out of thousands of acres. Squatters used this survey to justify being on parts of the Ranch that they believed to be "government land." The availability of water only exasperated things, attracting groups of unauthorized dwellers that often dug their own ditches to divert the water away from the Azusa River to their own rogue settlements. The struggle continued for years, even after Dalton's attempts to make peace with the squatters. Dalton recorded in his ranch diary in 1870 an encounter with a squatter whom he believed was stealing his water:

I told him that I would break the hand that touched it; he did it and I struck his hand as hard as I could (with a walking stick). He then pushed me into the zanja and drew his pistol to fire upon me. Marcos (Dalton's ranch hand) came up and drew a pistol and ordered him to put up his pistol or he would fire upon him; he finally put up his pistol and after some words withdrew.

As the number of squatters increased, so did their political powers. By the 1870s, local districts, including the courts, were controlled by the squatters, who formed their own water district and planned to build a new irrigation system on Dalton's land. Despite Dalton's appeals to the State Supreme Court, with no support from the local government, he had no choice but to give up the fight for his land and water -- and with it went his dreams of becoming a wealthy California ranchero.

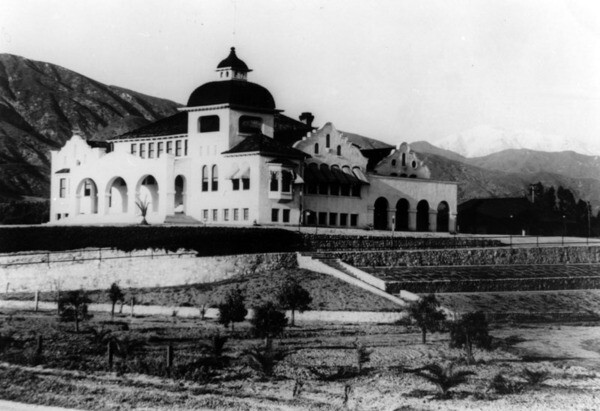

In 1886, the Santa Fe Railroad arrived to Los Angeles. This led to a spectacular land boom that ballooned the city's population, from 11,000 in 1880 to 50,000 by 1890. Dalton had died in 1884, just a few years too soon. His beloved Rancho Azusa would soon become the City of Azusa, a bustling foothill city that served as the gateway to the increasing recreational opportunities offered by the San Gabriel Mountains, where his legacy remains in the form of a popular hiking trail, Big Dalton Canyon.

____

Sources:

Baker, C.C. "Don Enrique Dalton of the Azusa" Historical Society of Southern California, 1917

Cornejo, Jeffrey Lawrence Jr., "Azusa" Arcadia Publishing,2007

Jackson, Sheldon "The Life and Times of Henry Dalton and the Rancho Azusa" A. H. Clark Co., 1977

Robinson, John W. "The San Gabriels II" Big Santa Anita Historical Society, 1981