Life at Marrano Beach, the Lost Barrio Beach of the San Gabriel Valley

Marrano Beach never appeared on maps of Los Angeles County's 75-mile coastline. It registered no international acclaim like the behemoths of Santa Monica, Manhattan, or Redondo. It had no brackish tide pools or cool Pacific breezes. There was not a chance of a surf advisory because waves didn't even lap its shores. Marrano was a beach without an ocean.

It was an anomaly that begged the question: "Where in the hell is Marrano Beach?"

The query has been printed on jackets, t-shirts, and even clocks since the late twentieth century. Marrano Beach was actually deep in the San Gabriel Valley, unfolded on a swath of marsh land wedged in the Whittier Narrows along the Rio Hondo River. It was miles from the sea, but its history as an inclusive recreational destination popular with local Mexican Americans communities throughout the twentieth century endowed it with a tenacious cultural heritage unlike any other beach in Los Angeles.

The origin of Marrano Beach can be traced to the early barrios, or neighborhoods, that arose around the original San Gabriel Mission in the late 1700s. Adobe homes of a Mexican village known as La Mision Vieja arose on mission land in the lush floodplain between the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo Rivers. The barrio became one of several communities established in the Narrows, housing laborers tending to the region's robust plain of crops that were regularly enriched by river sediment.

Within a few decades, neighborhoods near La Mision Vieja came to include La Mision, Canta Ranas, and El Rancho de Don Daniel. Marrano Beach was born on the riverfront property of El Rancho de Don Daniel, a Mexican land grant from the nineteenth century that had belonged the Repetto-Alvarado family, a prominent family of California land owners. El Rancho de Don Daniel encompassed riparian wetlands and ponds surrounding the Rio Hondo, which flowed year-round, and the seasonal Mission Creek. With few opportunities for respite after toiling in the fields, residents of the barrios cultivated recreational lifestyles around this section of the river and embraced it as a bucolic resource for community and family activities.

In the twentieth century, the profile of El Rancho de Don Daniel transformed from a pastoral space of leisure to a symbol of active cultural identity in an era of segregation. By serving as an alternative space of recreation for Mexican Americans affected by policies of racial discrimination applied at recreational zones in Los Angeles, the beach became a place to enforce their cultural claims to the land. Locals created what Victor M. Valle and Rodolfo D. Torres call in "Latino Metropolis," "an oppositional model of cultural space."

In the early 1900s, Mexican Americans and other minorities in California were forbidden from entering "Whites Only" spaces such as parks, beaches, and swimming pools. Public park options were limited to East Los Angeles due to the hostility encountered in green spaces in other parts of the city. By 1923, all Los Angeles-owned public pools were racially segregated. Mexican, Asian, and African-Americans could often only attend the pools when the whites vacated the swimming areas once a week -- the day before the city cleaned the pools.

William Deverell notes in "A Companion to Los Angeles" that neither backyard pools nor air conditioning were common among middle class residents until the 1950s, leaving working-class residents few options for relief from the oppressive heat of summer. This exclusion also applied to the beaches of L.A.'s coastline. By the 1920s, the city and county of L.A. purchased beaches within its borders to ensure white-ownership of seaside properties, protecting one of the city's most prized recreational and tourist assets from the perceived menace of racial intermingling.

In response, Mexican Americans in the far inland reaches of the San Gabriel Valley devised their own "beach." It was during this era in the 1930s that El Rancho de Don Daniel also came to be known as Marrano Beach. In "Blowout! Sal Castro and the Chicano Struggle for Educational Justice," Mexican-American educator and activist Sal Castro recalled his experience growing up in East L.A. in the 1940s: "To compensate for this discrimination and exclusion in swimmings pools and parks, Mexicans, including my family, went to what was called Marrano Beach." The origins of the name Marrano, a pig or hog, are numerous, including that the murky stretch in the river resembled a pig trough, that a pig farm once existed upstream, or a that a flood swept through a local ranch and deposited pigs on the river's shore.

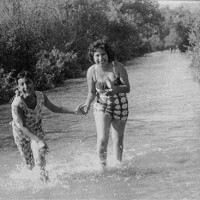

The name marrano linked the space to the agricultural heritage of barrio life in the Narrows. It was a self-deprecating reference to the socioeconomic realities of local residents, a name choice that Valle and Torres posit that "stressed their class orientation, especially their lack of public recreational and transportational resources, but also their resourcefulness in the face of poverty." Unable to attend or afford swimming lessons in city pools, children like Sal Castro learned to swim in the beach's shallow waters. Couples could socialize on the shore with a pot of menudo, and children enjoyed refreshing raspadas, or snow cones, sold from small stands. Singers and mariachis would work the sandy shores, serenading sunbathers and striking up dances into the night. "If they could not afford to live in homes with swimming pools or transportation to a real beach," Valle and Torres add, "they could at least enjoy their imagined beach during the hottest months of summer."

When freeways struck through the San Gabriel Valley midcentury, the pastoral allure of the beach began to rust. On the heels of freeways that brought easier access to the Pacific coast, oil wells and factories followed and soon spoiled the area's peaceful vitality. Pollutants would seep into the Rio Hondo, stirring an acrid smell into the water. In his memoir "Always Running: La Vida Loca: Gang Days in L.A.," Luis Rodriguez recalled the scene, depicting the pride that nonetheless survived the more abrasive elements:

In the summer time, Marrano Beach got jam-packed with people and song. Vatos Locos pulled their pant legs up and waded in the water. Children howled with laughter as they jumped in to play, surrounded by bamboo trees and swamp growth. There were concrete bridges, covered with scrawl, beneath which teenagers drank, got loaded, fought and often times made love. At night, people in various states of undress could be seeing splashing around in the dark. And sometimes, a body would be found wedged in stones near the swamps or floating face down. The place stunk, which was why we called it what we did. But it belonged to the Chicanos and Mexicanos. It was the barrio beach. Ours.

It remained for Rodriguez and others a preferred destination, given the animosity that still lingered on the Gabacho beaches, or white people's beaches. On his weekly "The Sancho Show" on KPCC-FM in the 1990s, Dr. Daniel Castro, a.k.a. Sancho, would jokingly refer to his past visits to the Marrano Beach Club. The fictitious club was a local lampoon of the exclusive institutions of leisure on the Westside, a symbol serving to deflate the stigma of discrimination. "If one knows Marrano Beach, one knows something of the Mexican, Chicano, East Los Angeles experience," Rita Lesdesma writes in "Lessons from Marrano Beach: Attachement and Culture."

Despite the beach's strong connected heritage with local residents, the steadily polluted area was eventually strangled by unchecked riparian growth. The prolific bamboo and invasive swamp plants of Rodriguez' Marrano Beach cut off access to the river's shores, shuttering a blazing era of recreation in this small patch of the Narrows.

The beach was lost, but this buried portion of the Rio Hondo still flowed unrestrained, spared a concrete lining that eventually dressed the rest of the river. The value of this free flowing waterway and the potential for reclaiming its riverfront shores was eyed by revitalization efforts in the 1990s, championed by County Supervisor Gloria Molina, a La Puente native with fond memories of Marrano Beach. Non-native plants were removed, picnic tables were installed, and the area was renamed Bosque Del Rio Hondo Park, or forest of the deep river. The Emerald Necklace network of parks and trails, spearhead by Amigos de los Rios, links the the five-acre Bosque to other park projects located along a 17-mile loop of river-adjacent trails and greenways.

Visitors to Marrano Beach today are warned by signs to stay out of the river. It's now a beach without access to its water, which may strike some as odd. But Marrano Beach, close to thirty miles away from the Pacific Ocean, was never a common shore. It was born from those spurned by discrimination, led to conceive their own spot in the sand.

What are your memories of Marrano Beach? Leave a comment.