Circles: Healing Through Restorative Justice

This is part of a series examining Restorative Justice in schools and communities, produced in partnership with the California Endowment.

"Who or what inspires you to be your best self?"

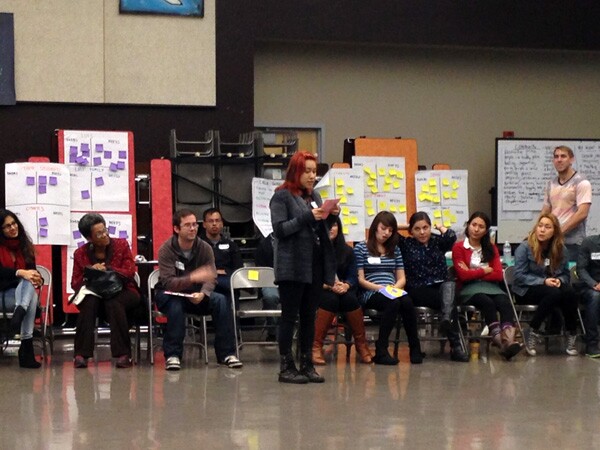

This is hardly the question that most Angelenos would ask at 9:30 in the morning on a gray, rainy Saturday. But for the 80+ adults and youth who gathered on March 2 at Mendez Learning Center in Boyle Heights, this introspective query kicked off "Circles," a rich, daylong exploration of Restorative Justice.

Restorative Justice (RJ) seeks to cultivate both peacemaking and healing by facilitating meaningful dialogue. Practiced through conversation circles, whose norms include "listen with respect" and "speak from the heart," RJ provides contexts for sharing feelings and perspectives related to community issues and conflicts. Individuals directly engaged in altercations, as well as bystanders and other community members, gather to discuss inciting incidents, understandings, preferences, past experiences, ideas, and advice.

According to one Circles participant, a senior at Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights, RJ works. He and a peer had a falling out this past fall -- he had criticized the peer and then they began fighting. Both were invited to a RJ circle to work it out. The circle, populated by fellow students and facilitated by a trained RJ counselor, gave the two young men a space to air their grievances and, importantly, get to know each other. In Aceves's opinion, this was critical. Now the former combatants are good friends, hanging out together practically every weekend.

While this rosy outcome isn't typical, RJ increases the likelihood of such a relational development. Compared to traditional responses, like turning a blind eye, assigning short-term mediation, or sentencing wrong-doers with detention, suspension, or expulsion, RJ's odds of building interpersonal bridges is infinitely superior.

Traditional justice systems use punishment, such as zero-tolerance, to deter students from breaking rules, whereas RJ assumes that strong relationships and community investment function as deterrence. Traditional justice systems are reactive and atomistic, meting out consequences to perpetrators of discrete, forbidden acts -- for instance, suspending the student who threw the first punch. But RJ is proactive and collectivistic, engaging a network of students before and during negotiations of conflict. RJ is also restorative, aiming to support participants in healing, problem-solving, and making amends.

Omar Ramirez, a visual artist with the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, and who served as a Circles small group leader, frames RJ as a means to shut down the "school to prison pipeline." RJ might help to do this in several ways.

Because RJ is a dialogic alternative to suspension and expulsion, it breaks the cycle of disproportionately meting out punitive disciplinary consequences to students with disabilities and students of color. This stops the implicit messaging that these students are unwelcome in school, and helps to keep them off the streets. According toThe California Conference for Equality and Justice, a suspension at any point during high school makes a student three times more likely to drop out than a peer who has never been suspended.

Additionally, it's possible that RJ participants who acquire tools for communicating and managing emotions will find it easier to resist criminal activity. Participating in RJ also might help youths to engage in perspective-taking and practice empathy, both of which boost negatively predict bullying and boost students' social and emotional competence. This is critical, since researchers from Sonoma State University have contended that "deficits in emotional competence skills appear to leave young people ill-equipped to cope effectively with interpersonal challenges." 1

Due to RJ's capacity to both support students' social-emotional health and contribute to school climate change, members of the Building Healthy Communities - Boyle Heights (BHC-BH) collaborative have championed its practice. Building Healthy Communities is an effort of The California Endowment to support 14 communities' holistic health; Boyle Heights, as well as Long Beach and South Los Angeles, are among these communities. Forty non-profits and community-based organizations comprise the BHC-BH collaborative. Its mission, according to BHC-BH's campaign literature, is to "meet with resident and youth leaders to establish efforts that will improve the health narrative of Boyle Heights."

Pilot RJ programs launched in Long Beach and at Boyle Heights's Roosevelt High School this 2013-2014 academic year. But to scale up RJ and implement it in every school in Boyle Heights (not to mention every Los Angeles Unified School District institution), funding is necessary -- specifically, funding to support the salary of each school's full-time RJ counselor.

In this context of state-wide budget deficits, locating any money at all requires creative activism. BHC-BH has identified as its RJ funding solution the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Introduced in California's 2013-2014 budget, the LCFF provides grants for schools that serve foster youth, English Language Learners, and/or youths eligible to receive a free or reduced-price meal. This describes many of Boyle Heights' students.

Las Fotos Project presented the Circles workshop, in partnership with several community-based organizations: The Greenlining Institute, the California Conference for Equality and Justice, InnerCity Struggle, Khmer Girls in Action, Violence Prevention Coalition, and Alliance for California Traditional Arts. 2 Together, they defined the workshop's objectives, which included raising attendees' awareness of the BCH-BH, educating them about LCFF, and inviting them to urge officials to direct local LCFF funds towards RJ. According to Eric Ibarra, founder of Las Fotos Project, the March 2 workshop also was inspired by his pride in his students' photo essays.

Ibarra's Las Fotos Project seeks to empower Latina youth through photography, mentorship, and self-expression. Whereas five of Ibarra's students last year premiered their photo essays online, this year Ibarra yearned to share his students' projects with live audiences as well. Moreover, since this year's photo essays examined RJ, Ibarra wanted audiences to explore RJ hands-on, learn about how RJ can be funded locally, and access pathways to activism.

That's precisely what the Circles workshop offered. After attendees shared who or what inspired them to be their best selves, they watched a photo essay created by Las Fotos Project participant Lorena Arroyo. A 17-year-old Roosevelt High School student, Arroyo documented cheerleader Gaby's explorations of RJ within her squad. Following the photo essay presentation, Arroyo proudly bowed to Circles attendees' thunderous applause. Four more of these media projects, highlighting the respective RJ journeys of two students, a parent, and a school staff member, will be forthcoming from Las Fotos Project participants.

Explained Ibarra, Circles represents "the efforts of a lot of really passionate people ... We believe in the importance of collaboration and sharing resources to work together for a common cause."

Rich in geographic, ethnic, and occupational diversity, Circles attendees seemed to share that collaborative ethos. For example, Circle #3, facilitated by Ramirez, included three high school students, a community organizer, a nun, a PhD candidate [myself], a high school teacher, and an editor [of KCET Departures], all of whom eagerly embraced RJ's community spirit. Establishing our own dialogic circle gave us a space to learn about RJ and each other. We shared and, more importantly, deeply listened to personal stories about a Native American grandmother, a growing daughter, an insensitive coworker, a resilient student, and a passion for '80s fashion. We also discussed RJ definitions and how to conduct circles for addressing teacher-student conflicts.

To close the workshop, each Circle group practiced and promoted RJ through the use of a different art form, e.g., collage, journaling, breakdancing. Articulated members of the spoken word circle, "I am a beautiful dreamer, I am a strong fighter." Members of the songwriting circle entitled their tune, "We Want to Restore Justice." Together they sang the refrain, "This is ours/People power."

In the view of 20-year-old Anaheim community organizer Carlos Becerra, the implications of this people power can be revolutionary. Stated Becerra, "Restorative Justice, when implemented in our global community, has the potential to create world wide peace and prosperity."

_____

1 Buckley, M., Storino M. & C. Saarni. (2003). Promoting emotional competence in children and adolescents: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), pp. 177-191.

2 In partnership with Building Healthy Communites Boyle Heights, Weingart East Los Angeles YMCA, People's Yoga, East LA Women's Center, and KCET Departures. The event was funded by The California Endowment.