Historic Monuments of Ethnic L.A?

PART 1 - CHINATOWN

Los Angeles is the quintessential 21st Century, multi-ethnic metropolis. 52 to 56% of the county's population is of Mexican and Central American descent, the San Gabriel Valley is home to one of the fastest growing Chinese and ethnic Chinese populations in the nation, first and second-generation Koreans have made Los Angeles their second Seoul and Middle Eastern immigrants from Lebanon, Pakistan and Iraq have created their own "Little Arabia" not far from Disneyland.

There's no doubt that Los Angeles' complex ethnic mix reflects global social changes and migrations, but this is nothing new to our city. In his influential book, The Los Angeles Plaza, Historian William Estrada traces the city's multi-ethnic status from indigenous and colonial times to present-day Los Angeles, weaving together a common narrative based on personal stories, news clipping and diaries about the heart of Los Angeles. According to Estrada, Los Angeles was a multi-ethnic city from its inception, with Native-Americans or Gabrieliños, Spaniards, Mexicans, Chinese, Anglos and Africans negotiating and defining the meaning of the city.

Through this lens of common recognition, Departures has gone about exploring Los Angeles, weaving together "official" and personal stories that celebrate, uncover and remember our shared history. It's no surprise then that when we visit places rich with myths and forgotten histories we encounter issues that highlight ongoing - sometimes fraught - efforts telling true stories of culture, history and race in Los Angeles.

Chinatown is a great example of how difficult it can be to uncover these histories. It took almost three decades of dedicated efforts by community leaders to open the doors of the Chinese American Museum in 2003 and "officially" tell the story of the first wave of Chinese Immigrants to Los Angeles and the destruction of Old Chinatown for the construction of Union Station. While many people knew of this history, there had been no formal "above ground" recognitions by the city.

This tension between official and informal monuments can be found throughout Chinatown. Early Chinese entrepreneur Fong See, immortalized by Lisa See in her family memoir On Gold Mountain, built a family empire around businesses such as F. Suie One Co. and Fong's Antique Shop. One simply needs to walk into one of these establishments - two of them are in Chung King Road - to step into a living piece of Los Angeles history. Yet because these are private businesses, many such informal monuments are threatened with closure and erasure.

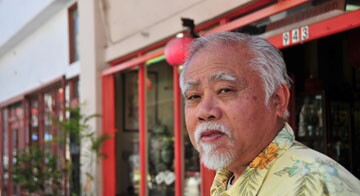

As part of the Chinatown Departures, I spoke with Leslee Leong, great granddaughter of the late Fong See and Mason Fong, cousin of Leslee, to discuss how these "unofficial" places of Los Angeles history should be maintained, preserved and celebrated as monuments of our common narrative.

PART 2 - THE WATTS TOWERS

Starting Oct. 22 an international discussion around some of these issues will kick off with a focus on the Watts Towers. As part of the Watts Towers Common Ground Initiative Seth Strongin, Policy and Research Manager at The City Project, conducted a series of interviews with N.J. "Bud" Goldstone - Watts Tower advocate and engineer - about the imminent danger facing the iconic south Los Angeles historical monument today.

The City Project, whose mission is to help shape public policy around issues of social and environmental and public equity with emphasis on communities of color, has taken the lead around building public awareness on this issue.

In his interviews with The City Project (see below) "Bud" Goldstone urges the city to turn the towers over to a private arts related entity that has the capability and expertise to maintain and preserve them.

Simon Rodia, the Towers' master architect and builder, gave the property away in 1955 and it changed hands repeatedly until it was deeded to the city in 1975 and become a historical landmark. But this "official" recognition was no guarantee of safety and support. After years of official neglect, the community had to take legal action to preserve them.

Today the towers are once again being threatened. Without a radical new approach to maintaining and preserving, the towers could go the way of many other lost monuments of Los Angeles' ethnic history.

Ironically, as Bud" Goldstone suggests, taking the towers away from the city might be the only way to save them.