Walter H. Leimert and the Selling of a Perfect Planned Community

A segment based on this story was produced for KCET's award-winning TV show "SoCal Connected." Watch it here now.

Looking at L.A.'s many pre-WWII neighborhoods, it's easy to forget that many of them were created as pre-planned subdivisions, as manufactured as today's much-maligned suburban gated communities. We'd like to think of old charming blocks of bungalows and small businesses as having grown organically, with each new phase of development based on the notion of supply and demand, but most often than not, they have been results of careful planning.

The South L.A. neighborhood of Leimert Park is known for its modest, well-kept Spanish-style homes and eclectic businesses centered around Degnan Boulevard, which, as the Leimert Park Village, has carved out an identity over the past several decades as the center of African American arts, culture and identity. This relatively recent development can indeed be attributed to an organic growth, resulting from a variety of historical events, from WWII, the growth of suburbia, Watts uprising of 1965, or the L.A. Riots of 1992.

But the 230-acre neighborhood had its genesis as one of the first master planned communities in Los Angeles -- the vision of a shrewd, prolific developer named Walter H. Leimert.

East Bay to the Eastside

Walter H. Leimert was born in 1877 to German immigrant parents in Oakland, who had opened up a candy shop and owned several properties in the city, including a commercial building downtown now known as the Leimert Building in Old Oakland.

Soon after forming his namesake company in 1902, Walter H. Leimert began his quest to create the perfect neighborhood. By 1917, in the Oakland hills northeast of the fashionable Lake Merritt area, he had developed the Lakeshore Highlands, its plans laid out by frequent Leimert collaborators, the Olmsted Brothers. The subdivision was designed and marketed as the ideal trolley suburb with modest, affordable homes, with street cars providing easy access to the urban amenities of San Francisco and the intellectual hub of Berkeley. Promotional material of the day emphasized the short 36 minute commute from the Highlands to the bustling Market Street across the bay: "No air service of the future can shorten this distance between your office and your home."

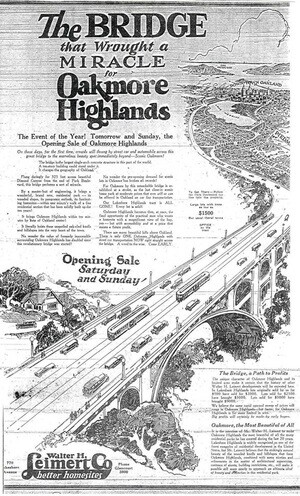

In 1926 Leimert built a grand bridge that crossed the deep Sausal Creek, providing automobile and street car access to the hard-to-reach areas of the Oakland hills, paving the way for development of Oakmore Highlands. At the time the bridge, Leimert claimed, was the longest single arch concrete bridge "in this part of the world." The street that crosses the bridge is now known as Leimert Boulevard.

By this time Walter H. Leimert had moved his family and base operations to Los Angeles, and had begun developing projects in the southland. After developing Bellhurst Park in Glendale, Leimert saw potential in the areas east of the L.A. River, speculating that the planned building of six major bridges would provide access between the rapidly over-crowding Westside and the untapped frontierland of the Eastside. In an advertorial piece for the L.A. Times, titled "City Swings East," published October 6, 1923, Leimert explained why the time was right for Angelenos to expand eastward and, more specifically, move to his latest development -- City Terrace:

Why did Los Angeles start growing southward and westward from the original business center instead of going equally northward and eastward? [...] The answer is the LOS ANGELES RIVER. To the north and east, lay a river, flanked with grade railway crossings and ards spanned only by bridges which have always been too narrow, always too rickety, always too short to reach from hill to hill. To the south and west there was no river and no tracks [...] With one stroke the voters of Los Angeles have WIPED OUT the barrier to the north and east. Bonds are voted to build, not one, but SIX viaducts--giant structures of steel and concrete, wide enough for all traffic, long enough to reach clear to the hills on the east, with easy approaches from the business center. The city has voted $2,000,000 in bonds for these viaducts.

Leimert, as the self-appointed "recognized expert on city development," assured potential buyers that "while development stood still out to the eastward, PRICES ALSO STOOD STILL. You can buy now at 1914 prices."

How You Can 'Live in the Park'

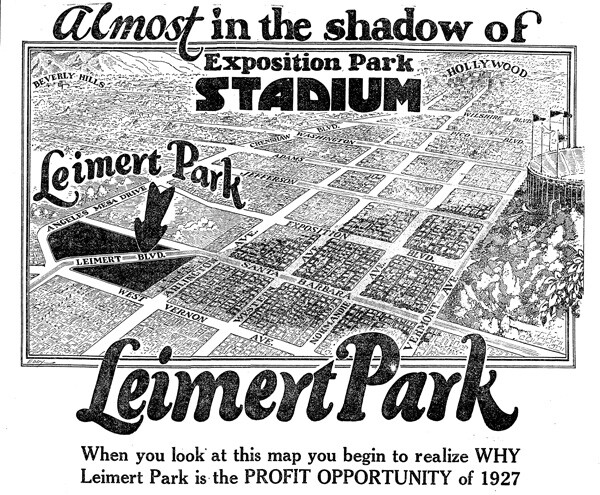

In 1927, in one of the biggest land transfers in Los Angeles at the time, Walter H. Leimert purchased 231 acres of land from Clara Baldwin Stocker, the daughter of the colorful land baron Elias "Lucky" Baldwin. The purchase was made after Leimert had surveyed the area and found that "only twenty-six vacant homes were found in more than eighty square blocks." This property, part of Baldwin's Rancho La Cienega -- once one of the most profitable dairy farms of the region -- was bounded by Santa Barbara Avenue (later Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard) to the north, Arlington Avenue to the east, Vernon Avenue to the south, and Angeles Mesa Drive (later Crenshaw Boulevard) to the west. This became the blank canvas onto which Leimert would paint his vision for the perfect planned community.

Leimert once again teamed with the Olmsted Brothers for the layout of his latest subdivision. The "beautifully designed" Leimert Park was touted as being at the intersection of five major boulevards, and "square in the path of Los Angeles' march westward to the sea" -- somewhat of a self-inflicted blow to his prior hopes for City Terrace and his prediction for eastward expansion of the city. In fact, Leimert was so confident with this new westside development that for the first time in his career, he lent his own name to the subdivision. Expressing his excitement in an advertorial piece in the L.A. Times, "An Open Letter to the Public of Los Angeles," he wrote:

I have, now, for the first time, permitted my name to be applied to a subdivision. I do so because I am 100% convinced that the 230 acres I have purchased [...] present a magnificent opportunity for the creation of a very beautiful and highly successful residential and business development.

In another advertisement, the Leimert Company provided a list of 14 reasons "Why Leimert Park is the Best Place in All Los Angeles For Your Future Home." These included:

- Yellow Carline, 5c Fare

- Solid Concrete Streets

- Shade Trees

- Fine Schools

- Excellent Protective Restrictions

In his "Open Letter," Leimert described in detail what these "restrictions" entailed:

I am bringing to Los Angeles the Community Association Plan of protective restrictions -- new here, but well established throughout the Lakeshore Highlands property in Oakland and Piedmont where, largely due to the fine restrictions, values have increased 400% to 500% over original prices. By this plan of restrictions the control of the property comes into the hands of the property owners themselves when the subdivider steps out; and they can and do maintain the beautiful appearance of the property, both from an architectural and a landscaping point of view, FOR ALL TIME.

More often than not, such restrictions resulted in segregated neighborhoods, whether or not that had been the intended effect. In his book "The Shifting Grounds of Race," Scott Kurashige, referring to developments like Leimert Park, says that "in their quest to maintain community standards, the new and massive subdivisions proved to be the greatest progenitors of residential segregation." In fact, many subdivisions at the time included restrictions that explicitly barred certain races; for example, during his time in Oakland, Walter H. Leimert had been urged by the Olmsted Brothers "to include East Indians in his racial covenants -- and to add the phrase 'or any other races in the discretion of the Lakeshore Homes Association," according to Robert M. Fogelson in his book, "Bourgeois Nightmares: Suburbia, 1870-1930."

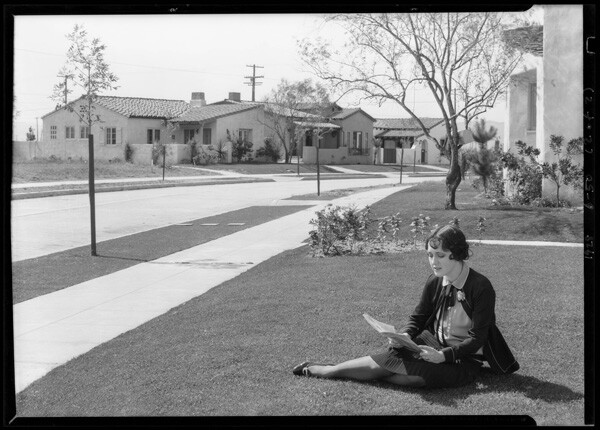

But, as potential home buyers "generally found restrictions to be far more desirable than onerous," according to Kurashige, such restrictions were just one of many selling points of Leimert Park. The Leimert Company began a blitz publicity campaign to lure potential buyers to the new development. A series of ads were placed in the local papers, boasting Leimert Park's investment potential, ideal location, and comprehensive amenities, which would include a brand new school and the multi-use Mesa-Vernon "drive-in" market. The road and building construction was meticulously documented in photographs, many featuring an "It" girl actress of the day nonchalantly posing by hard hat workers. Once the tract was ready for sale to the public, a flock of balloon signs and a proto-Googie arrow pointed to its tract office on Vernon Avenue, where a motorcade of luxury cars and hired actors attracted customers.

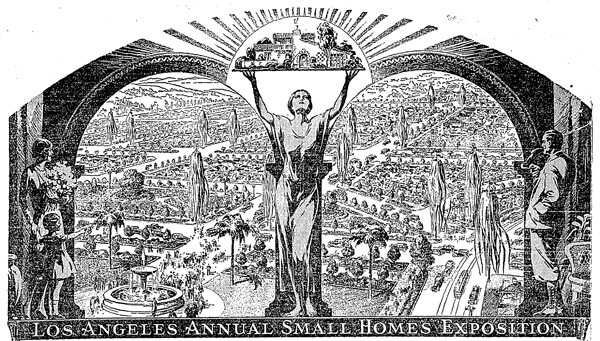

In 1928 the Leimert Company held the first "Small Homes Exhibition" to show off their model homes, to "show YOU how you can 'Live in the Park'." The types of homes on display included the "Modern Art Home," "Wood-Panelled Home," "the delightful Brick-Veneer home," and "the Story-and-a-Half Home," filled with furniture supplied by the venerable Barker Brothers.

Walter H. Leimert would go on to develop many more of the city's well-regarded subdivisions, including Beverlywood, Beverly Highlands, Cheviot Knolls, and Rancho Malibu. The Leimert Company operates to this day, most recently focusing their developing efforts in Cambria, CA.

For all of his accomplishments, Walter H. Leimert's legacy most recognizably endures in Leimert Park, which may not have the glamour of some of his other, perhaps more profitable, developments. But the neighborhood remains to this day as one of the most unique and attractive in all of the city -- staying true to Leimert's 100% conviction in lending the neighborhood his name.