The Center Can Hold: Leimert Park and Black Los Angeles

"We got to talking about Watts at a cocktail party," Mrs. Barbara J. Dyce told a Los Angeles Times reporter shortly after the devastating Watts Riots of 1965, "and we wanted to do something -- but we didn't know what." "Until the riots," the Los Angeles housewife confessed, "many of us never knew the problems." Dyce certainly was not alone: most Angelenos were baffled by the violence of African American youth who burned down their neighborhood in one of the most racially-tolerant cities in the Americas. Members of the McCone Commission -- the body appointed by Governor Edmond Pat Brown to determine the causes of the riots -- acknowledged similar bewilderment in the introduction to their widely cited report. "While the Negro districts of Los Angeles are not urban gems, neither are they slums . . . In the riot area most streets are wide, usually quite clean." That a mostly white, blue ribbon, commission could be initially puzzled by the searing resentment of black youth in Watts is not surprising. That Mrs. Barbara J Dyce was, might be: she was an African American resident of Leimert Park.1

A close look at the recent history of African Americans in Leimert Park suggests that Dyce's puzzlement was actually warranted. Nineteen Sixty Five and 1992 are easy touchstones in our collective memory of black Los Angeles, but the fact is, they are anomalous. Amidst the dizzying barrage of changes affecting black Los Angeles since World War II -- the rise and fall of unionized industrial work, the ascent and recession of black political power, the infiltration of gangs and drugs, the youth violence that has taken an unconscionable number of young men, and the ambiguous impact of Latin American immigration - it is sometimes hard to see constancy. Yet constancy is precisely what Leimert Park represents. Nurtured by three generations of African Americans with a shared vision of economic self-empowerment, the patronage of black businesses, the cultivation of black arts, and the maintenance of a public commons for political discourse, Leimert Park is not just the crown jewel of black Los Angeles, it is its center.

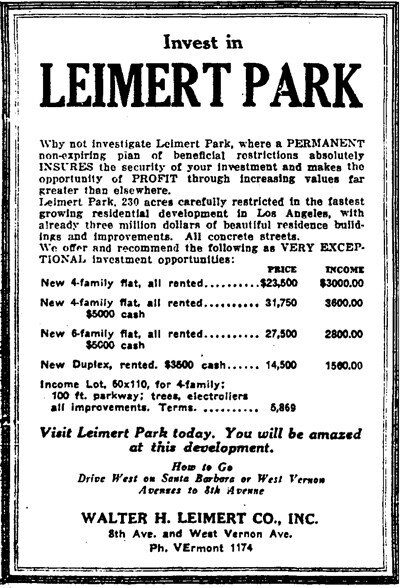

Nothing in the early history of Leimert Park prefigured its rise as the heart of black Los Angeles. In 1927, while a web of racially restrictive housing covenants still contained most African Americans North of Vernon and East of Vermont, developer Walter H. Leimert sold off the first units of his carefully planned community to eager white buyers. The homes were so idyllic that the Los Angeles Times sponsored a "house beautiful" educational campaign in Leimert Park, staging several homes with the newest designs in furniture, glassware, drapery, tile work, and floor coverings. The campaign drew an astounding 16,000 visitors on the first day, and several hundred thousand more in the following weeks.2

In the next nine years, Leimert erected 417 single-family homes, 170 duplexes and multi-family apartments, and scores of business properties, and vacancy rates never exceeded 1-2%. In other words, Leimert Park was a masterful business enterprise that created a beautiful, multi-use community, surrounding a small park that Leimert donated to the city.3

Like most desirable areas of the City, however, Leimert Park remained off-limits to African Americans until 1948, when the United States Supreme Court declared racially restrictive covenants legally unenforceable in its landmark decision, Shelley v. Kraemer. The Chicago Defender, African America's most trusted news source at the time, boasted: "The racial bigots in the field of housing have been completely routed."4 And, in what would become the first wave of "black flight" from historic South Los Angeles, affluent African American Angelenos immediately sought housing in Compton, West Adams, and Leimert Park. Predictably, however, white homeowners pushed back - hard. In the decade following the Shelley decision, whites across the County bombed six black homes, burned four more to the ground, and intimidated countless African Americans through an array of wicked techniques including death threats, cross-burnings and "KKK" scrawlings.5

Amongst the more genteel whites of Leimert Park, however, anti-black harassment took the form of old-fashioned vandalism and creative litigation. When new African American homeowners Mr. and Mrs. Charles Williams of 3775 Olmsted went out one evening, for example, they returned to find the entire interior of their home smeared with used motor oil. More significantly, a group of forty white homeowners, led by Marion M. Allen, filed suit against another white homeowner who sold his home on 3913 Sixth Avenue to a black couple, Mr. and Mrs. Preston Wilson. The group sued Oscar Reichow -- a well-known sports writer and business manager for the Hollywood Stars minor league baseball team -- for $185,000, the collective amount, they estimated, by which their property depreciated as a result of the Wilson's arrival.6 Reichow died a month later, depriving the petitioners their recompense, but the threat of litigation had a chilling effect on the willingness of white homeowners -- in Leimert Park and the rest of Los Angeles -- to sell their homes to African Americans. Finally, in 1953, the Supreme Court dealt the mortal blow to racially restrictive housing covenants by denying the right of homeowners like Allen to sue other whites for breach of contract.7 After 1953, the rush was on.

As well-to-do African Americans migrated to Leimert Park, they gained access to the best of what Los Angeles offered. In addition to the superior housing stock, Leimert Park boasted a premier shopping district, anchored by the recently completed Crenshaw Plaza, one of the first large malls in the United States. They sent their children to Audubon Junior High School, one of the many schools in the area regarded by the Department of Planning and many others as "superior." And they worked closely with white homeowners to maintain the racial balance of the district to prevent the "white flight" that affected other areas of African American "encroachment." Organized under the banner of "Crenshaw Neighbors," these homeowners met with white parents and school administrators regularly, and they also argued against the strident militancy of 1960s black radicals who represented -- as the organization wrote in its periodical, The Integrator -- "a nuisance to an integrated area" because they "scar[e] the daylights out of probable candidates for integration."8

Ultimately, Crenshaw Neighbors probably slowed white flight from Leimert Park, but it could not stop it. Yet, the usual effects of white flight -- the loss of capital, businesses, and employment opportunities -- were quite minimal in Leimert Park, when compared to the effects in Watts, Willowbrook, and other South Los Angeles communities. The African Americans of Leimert Park, it turned out, were sufficiently prosperous. A significantly higher proportion of black men in Leimert Park were professionals and managers than in other black neighborhoods, and their wives often worked steadily as professional and clerical workers.9 In addition to lavishing attention on Leimert Park's best known resident, Tom Bradley, the black press of the 1950s and 1960s regularly announced workplace promotions of residents at the Post Office, Fire Department, Florsheim Shoes, Thrifty Drug Store, and dozens of other establishments. Cultivating an image of black success had always been a central task of black newspapers; the accomplishments of Leimert Park residents made it an easy one.

Leimert Park was not immune to the roiling changes of the 1970s and 1980s, decades in which African American poverty skyrocketed nationwide because of the disappearance of industrial work; in which gangs exploited idled young men; and in which highly-addictive and dangerous drugs hit the streets. And Leimert Park residents also faced the challenge of maintaining community cohesion, as the most prosperous residents moved up into Baldwin Hills. But the commitment of remaining residents to keep Leimert Park special never died. In 1967, brothers Alonzo and Dale Davis opened the Brockman Gallery, "the premier venue for exhibiting black art in the city," according to historian Daniel Widener, and the hub of a citywide black arts movement.10 Residents led clean-up committees to erase graffiti, blocked efforts to add liquor stores to the area, and organized political action committees. And even as community gatherings in the park were less genteel than they had been in decades past, their organizers insisted on decorum. At the 1975 "Creator's Day" picnic and concert, organizers promoted a "family kind of situation," according to an editorialist for the Los Angeles Sentinel. "There were some wine bottles and an educated nose could find a path to Cannabis," but it was nothing like the Festival in Black or the Watts Summer Festival, where there were "angry young men, loaded to the gills on whatever drugs and looking for some way to get rid of all the hostilities they felt" and "girls were dressed in abbreviated costumes flashing their wares about."11 Finally, the crowning achievement of those challenging decades was the LAUSD's approval of a magnet school at the Dublin Avenue School in 1978, the first magnet in a black neighborhood, and an honor to the spirit and mission of Crenshaw Neighbors. In 1982, the California State Department of Education named Dublin an "Exemplary Model School."12

Neither the gang violence that seared the edges of the community in the late 1980s, nor the ferocious 1992 riots, crushed the spirit of Leimert Park. Devastated by the destruction of businesses on nearby Crenshaw Boulevard, Leimert Park community leaders responded with a renaissance, picking up where the Davis brothers left off after the closing of the Brockman Gallery in 1987. In 1989, jazz drummer Billy Higgins and activist Kamau Daáood opened the World Stage performance center; two days before the riots, Richard Fulton, an African American veteran who had lived for more than a decade on Skid Row, opened Fifth Street Dick's Coffee House; an arts space called "Project KAOS" (KAOS Network) opened and began hosting "Project Blowed" -- a free form hip-hop collective largely devoted to "deglamorizing gang life and repurposing the neighborhood," according to scholar Scott Saul. And Babe's and Ricky's Inn -- a longtime blues club on Central Avenue -- moved into Leimert Park in 1997. A more complete African American cultural revival could scarcely have been imagined.13

Today Leimert Park enjoys a distinction that would have shocked Walter H. Leimert, as well as the African American pioneers of the 1950s: more than 73% of its residents are African American, making it the blackest neighborhood in all of Los Angeles. Although older African Americans throughout the city often bemoan the "loss of community" in the face of Latin American immigration and the steady out-migration of blacks to the fringes of the County and beyond, the center is holding. It is there on a Friday night at the domino tables, at the remaining music venues, at the rallies in the park. It was there at the July rally to protest the verdict in Trayvon Martin's homicide, and there in September for the "Ready to Work" rally. The district is going through changes, with new landlords on the brink of squeezing out beloved spaces like the World Stage. But if enough young African Americans dedicate themselves to preserving the spirit of Leimert Park, nothing can snuff it out.

_______________________

1 Jack Jones, "Women Organize in Leimert Park to Assist Watts Area," Los Angeles Times 3 October 1966, pg. 3; Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, Violence in the City - An End for a Beginning? A Report (Los Angeles, 1965), 3.

2 Valerie Watrous, "Charm Rules Small Homes: Leimert Park Houses Prove Wealth of Artistry Can Be Installed at Minimum of Cost," Los Angeles Times, 24 January 1928, A1.

3 "Homes Demand Indicated," Los Angeles Times, 30 October 1927, E6; "Few Rental Vacancies in Leimert Park Area," Los Angeles Times, 16 August 1936, E2.

4 Loring B. Moore, "Court Can't Block Sales to Negroes," The Chicago Defender, 15 May 1948, 1

5 United States Commission on Civil Rights, "Hearings Held in Los Angeles and San Francisco, 25-28 January 1960," Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1960, 158-159.

6 "Hoodlums Damage Home," Los Angeles Sentinel, 15 March 1951, A1; "Owner Who Sold Home to Negroes Faces Damage Suit," Los Angeles Sentinel, 15 Jun 1950, A1.

7 Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953)

8 Los Angeles Department of City Planning, West Adams - Baldwin Hills - Leimert Socio-Economic Analysis (Los Angeles, 1971), 2, 26; The Integrator (Summer 1968), 2; Crenshaw Neighbors, Los Angeles Sentinel, 11 May 1972

9 These employment conclusions are drawn from comparing census tracts from the Leimert Park/Crenshaw area to Watts, Willowbrook, and other portions of South Los Angeles with significant black populations in 1960. U.S. Bureau of the Census Censuses of Population and Housing: 1960, Census Tracts (Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census, 1962), 576, 585-587.

10 Daniel Widener, Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), 158.

11Jim Cleaver, "Creator's Day: An Afternoon in Leimert Park," Los Angeles Sentinel, 21 August 1975, A7.

12"First Black Magnet School," Los Angeles Sentinel, 2 March 1978.

13Scott Saul, "'Gente-fication' on Demand: The Cultural Redevelopment of South Los Angeles," in ed. Josh Sides, Post-Ghetto: Reimagining South Los Angeles (Berkeley: Huntington Library and the University of California Press, 2012), 155