Getting Up, Staying Up: History of Graffiti in the L.A. River

"For us the river is like the last adventure in the city. We would go in tunnels under the river and you feel like you're the first person that's ever been down there, but then you start shining a light around and you'll see a tag that says some 'high school band, 1963'. It confirms that people were here before me," said Evan Skrederstu, a visual artist and co-author of the book "The Ulysses Guide to the Los Angeles River: Volume 1," that focuses on the biology and art of the river.

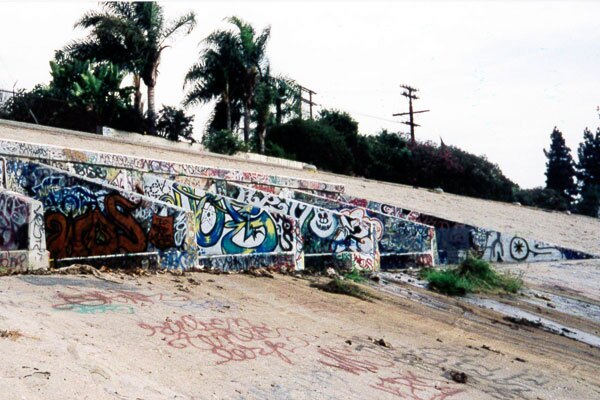

Skrederstu started painting graffiti in the river in the '90s when it was still a no-man's land. Sightings of a dead bodies, drug deals or shootouts were commonplace. Since the Army Corp of Engineers moved to channelize the river in 1938, the river's 51-mile stretch of grey concrete walls and low police presence has offered graffiti writers not only a large canvas for colorful murals, but also the lure of adventure in a place seemingly devoid of laws. Skrederstu's experience is not unique, with the river playing host to tags that date as far back as the early 1900s, making the river a physical timeline of the human experience along it.

Long before pushes for cleanup efforts and arts initiatives, the river was largely regarded as a repository for urban runoff. Graffiti artists were brought life and vibrancy to the river, something that had been missing since it was paved over. Even so, conversations about the future of the river have excluded graffiti artists who have been trying to carve out their place in larger plans for the river.

"This city is diverse and there are many creative thinkers and people who live [near the river and] grew up walking the river or who painted the river. Those are the people who should be involved with planning the future of it, and I definitely think as artists, we would be the best people to reflect the diversity of the city," said Alex "Man One" Poli, a Los Angeles-based artist and co-founder of the influential graffiti and street art gallery, Crewest, which closed its doors in 2012.

Referring to how deep graffiti's roots in the river go, Skrederstu points out that while researching for the book, he and other members of the artist collective, UGLAR (United Group of Los Angeles Residents), saw graffiti that predated the channelization of the river. One tag dates back to the early 1900s and was found on the rafters of a bridge near the Arroyo Seco Confluence. It read "Kid Bill 8-3-14" in Western font. It is believed that the tag and others like it, often with "Kid" preceding the name, was left by vagrants who traveled by the trains that line the river. The group also found graffiti left by Pachucos, or "Zootsuiters," in the river from the 1940s. One piece read "Killer de Dog Town 8-9-48" and was written with tar collected from a local train yard and painted in the rafters near the historic William Mead Housing Projects near Main Street in Downtown Los Angeles. Living in the poverty-stricken neighborhoods surrounding the river, Pachucos would mark the territory of their gangs, which had formed in the face of the increased racially-motivated violence and discrimination against the young Mexican Americans.

"Flash forward a couple of years and we start seeing graffiti in the river that set the stage for what graffiti is today," said Skrederstu of the first highly-stylized graffiti art pieces that started popping up along the river's embankments in the 1980s by graffiti artists like RISK and FRAME, who are now seen as pioneers of Los Angeles graffiti. Los Angeles in the early 1990s endured high instances of gang violence and murders, as well as an increase in racial tensions following the police beating of Rodney King and the murder of Latasha Harlins. The uptick in gang and police violence coincided with an explosion of gang graffiti and "tag banging" which made for a dangerous time for graffiti writers as there was a green light for gang members to shoot any tagger that entered the river. However, the violence of the early '90s slowly burned out. Many taggers went to jail or got absorbed by gangs, Skrederstu said. This left the river open for graffiti artists in the mid to late '90s and brought on a wave of large-scale, colorful graffiti art pieces.

"These crews that came out of L.A. are now world famous and are known for painting freeways and the river, whereas New York was known for hip hop and subways. The river made L.A. a force to be reckoned with in the graffiti world and it still is. A lot of the heavy hitters and world-wide influence comes out of L.A.," Skrederstu said.

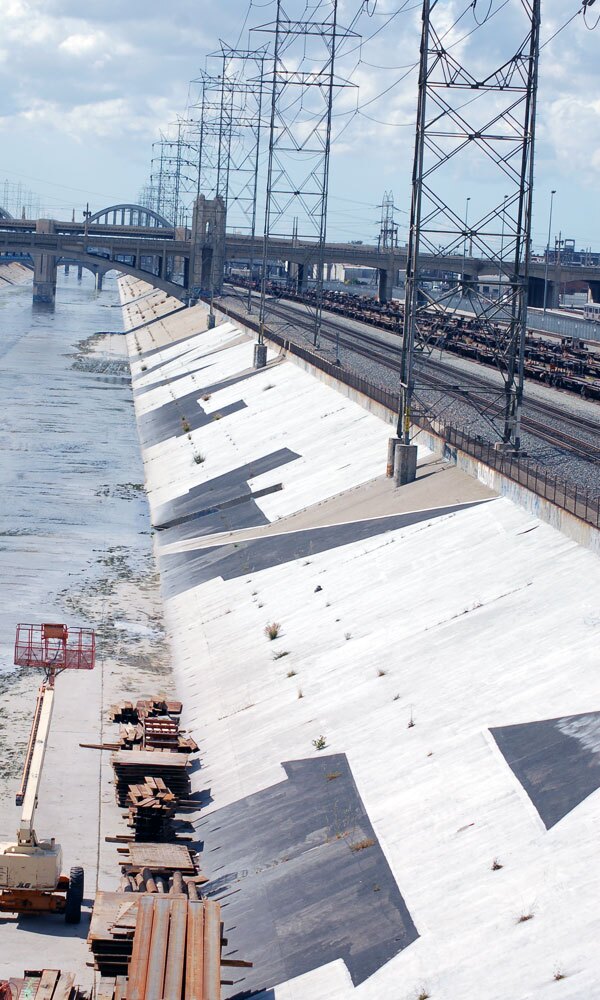

Crews like MSK "Mad Society Kings" have gained international notoriety in part because of their stellar graffiti artists. MSK's SABER, painted one of the world's largest graffiti art pieces along the river's embankment near the 5 freeway in 1997. Another notable MSK writer, REVOK, exhibited his work in MOCA's "Art in the Streets" exhibit, the first major museum exhibition of graffiti and street art in the U.S. Graffiti writers in the MTA "Metro Transit Assassins" crew also gained international notoriety in 2008 for painting another of the world's largest pieces in the river — a half-mile long "MTA" tag written in block letters near Fourth Street and the 101 freeway. Both historic tags were painted over with a coat of grey paint in 2009, when the Army Corp of Engineers used $837,000 of federal stimulus money to paint over the 45 miles of river that fall in its jurisdiction.

MTA's piece moved the Los Angeles City Attorney's office to make an example of them by threatening them with a $3.7 million fine for the buff-out. L.A. Weekly reported that those charged settled with the city attorney's office for thousands of dollars in restitution, community service, graffiti removal and an agreement from the defendants to not tag again.

"Instead of spending that money on painting over the graffiti, they could've given me a million dollars. I could've gotten a lot of artists to paint the river for the same price and we could've created something beautiful instead of a prison cell-looking river," said Man One. The threat of receiving a misdemeanor, felony or a hefty fine -—which is often in the thousands of dollars — is a reality graffiti writers in Los Angeles have to deal with. Despite the consequences and the threat of a graffiti injunction resembling the city's gang injunctions, artists like SABER and those from MTA are now selling their work in fine art galleries across the U.S. and overseas.

Actions Against Graffiti Art in the River

The rush of development brought on by revitalization efforts in river-adjacent communities has nearly doubled the housing prices since 2012 in places like Elysian Valley — or "Frogtown" — and has brought with it trendy coffee shops, boutique retail stores and craft brewing companies. This has left many longtime residents concerned about displacement and their community changing into one that they will no longer be able to identify with or live in. Unwanted or not, the neighborhoods near the river have always been high-impact zones for graffiti and tagging and have recently seen an increase in graffiti in and out of the river. According to Paul Racs, director of the Office of Community Beautification, this is part of a citywide increase.

As the population of the neighborhoods changes, bringing an influx of affluent white residents to the area, the newer residents have taken graffiti abatement efforts into their own hands. The Los Feliz Neighborhood Council hosts cleanup events that include graffiti cleanup once a month and the Elysian Valley neighborhood council has organized EV Beautification Day, in which residents clean up trash and graffiti. The Army Corp of Engineers also takes heavy measures to keep graffiti out of the river, spending nearly $250,000 a year to buff out graffiti along the river's 90 miles of embankment that fall in its jurisdiction. The contractors tasked with graffiti removal inspect the river on a routine basis and try to cover up graffiti within 24 to 48 hours, said Jay Field, a spokesperson for the Army Corp.

"The newer residents demand more city services, like graffiti cleanup," said Gina Chavon, senior lead officer at the North East Los Angeles Police Department, whose jurisdiction includes many of the communities that lie along the 11-mile stretch of the river slated for improvements in the city's river revitalization master plan.

In an area like Northeast Los Angeles, where violent crime rates have increased by 60% since 2013, Chavon said patrolling the river is currently not a priority for the NELA Police Department, which usually does not enter the river unless somebody calls. They do patrol the bike path regularly, she added.

The Future of Art in the River

The newer forms of art popping up along the river are different from their not-so-legal predecessors and are often facilitated by river organizations. Clockshop, an arts organization based out of Elysian Valley, has commissioned artist Michael Parker's project "The Unfinished," an excavation of an obeliskcarved out of the asphalt in an industrial lot next to the river. Artist Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio are currently working on "La Noria", a large 60-foot functional water wheel that will be built in the river near Los Angeles Historic State Park. Graffiti artists have also been able to collaborate with river organizations to bring art to the river. In 2007, Man One and Friends of the L.A. River (FoLAR) partnered to bring the "Meeting of Styles" to the river. Over the span of two days, the event brought more than 200 local and international graffiti artists to paint in the river near the Arroyo Seco Confluence. Graffiti artists transformed the grey walls with kaleidoscopic colors and images of colorful characters and scenes inspired by the city. One mural paid homage to the wildlife of the river and featured a green spotted pacific tree frog and a grey and white egret next to a storm drain cover and a city worker dressed in orange. The legal murals were eventually buffed out following threats of hefty fines by Gloria Molina whose spokesperson, Roxane Marquez, was reported saying that they were "a public nuisance and potential safety hazard".

Man One and FoLAR continue to work together on projects, including a live painting that will be auctioned at this year's FoLAR Fandango in October. They are also working on securing permits for a self-funded mural by Man One called "#FacesLA," that will feature portraits of Angelenos. Clockshop has also made efforts to bring graffiti artists to the river through their Con/Safos project, a collaboration between L.A.-based artist,Rafa Esparza and Self Help Graphics, an East Los Angeles community arts center. Esparza and his father built two intersecting adobe walls at the Bowtie Project that will feature the work of graffiti artists, painters and sculptors throughout the year. So far, Con/Safos has hosted the work of L.A. graffiti artists Roach and Leo Limon, who is known for the L.A. River Catz, cat faces he started painting on storm drain covers in the river more than 35 years ago. Most recently, the L.A. Public Art Biennial, which just received $1 million in funds from Bloomberg Philanthropies, plans to bring the work of 15 multidisciplinary artists to the river, although artists have yet to be chosen. The project aims to use the art as a platform to bring attention to the issue of water conservation.

"Graffiti artists have been wanting to be at that table [planning for the future of the river] all these years. When we planned 'The Meeting of Styles,' that was one action that we took as graffiti artists to say we want to be a part of this river and its future and we were denied," said Man One. "River organizations want artists to be involved but the issue is working with the city because they are the ones that hold the permits and funding for the projects and that hasn't happened."

As graffiti fines remain high and the threat of arrest is a reality, graffiti artists continue to get up. A city cooperating with graffiti artists in order to bring art to the city's bare walls is not unheard of. For example, Saint Louis, Missouri, eventually decided to take the "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em" approach after an unpermitted annual graffiti event continued to cost the city millions of dollars in cleanup costs since 1995. In 2013, the city finally embraced the event, "Paint Louis," which saw more than 300 artists and 1,000 attendees.

Man One holds to the idea that the concrete walls of the river are some of the most opportune places for murals. He hopes to see graffiti art parks and "free zones" where anyone can request a permit to paint, similar to the legal graffiti wall in Venice Beach.

"All of us artists agree that the river should be painted. Imagine a big 51-mile long piece of art snaking through the city that could be seen from passing airplanes, it would be beautiful. Why can't we create landmark like that? Instead of the city fighting a futile battle with keeping the river graffiti free, why not work with the artists to create something that's epic?," asks Man One.