Behind the Sign: The Lost Meanings of the Original Hollywood Sign

It seems a little crazy, Lost Landmarks spotlighting one the most recognizable landmarks in the world. Just below the summit of Mount Lee, this strange arrangement of giant letters in sans serif font attracts thousands of tourists daily. They clog Beachwood Drive, posing for cell phone and video cameras, oblivious to the frustrated locals just trying to get home. This thoroughly modern icon has been so infused with myth and build-up that my mother, an avid old movie fan, said upon first seeing it in person: "Well, that's disappointing."

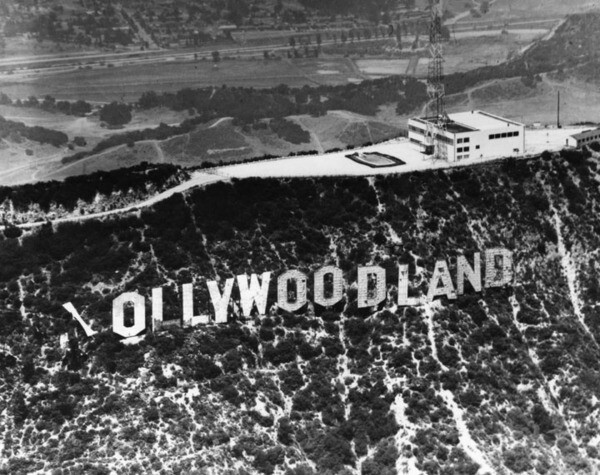

The sign we see now is not the original, constructed in 1923 with telephone poles, thin metal, wood, wire, and pipes. In true Hollywood fashion it is a remake, a sturdier and enameled copy of the first, reconstructed in 1978 with money from a disparate group of Hollywood aficionados. Both signs have been blatant advertisements -- the first for Hollywoodland, a secluded, upper-class neighborhood that promised a life high above the hoi polloi and smog of the city below; now what the sign sells is more intangible -- a dream of fame, wealth, and glamour luring scores of hopefuls to the city each year.

Recently, a few friends and I, who all had moved to Los Angeles in search of our slice of that Hollywood pie, set out on the Hollyridge Trail for the 45 minute hike to the summit of Mount Lee. We were surrounded by tourists on the dusty trail. There was a flight attendant from Florida on layover. A group of unruly European teenagers jumped over each other, one almost knocking me off the trail into the valley below. When we got to the summit, we competed with the crowds for a space to take pictures. Standing behind the 45-foot tall letters, they looked flimsy, like something at a temporary state fair. But oh my, the view below -- we could see downtown, the Griffith Observatory, the Hollywood Reservoir, and the Westside. When we turned around we saw Disney and Warner Brothers Studios, and the endless Valley. A police helicopter hovered above, and another helicopter seemed to disappear just below the large communication tower that sits above the sign, like an askew exclamation point. It was just like the beginning of a movie, we said.

Community Spirit and High Ideals

Hollywoodland will afford many decided advantages in addition to the clean, healthful atmosphere and the beautiful outlook of the hills. --Los Angeles Times, October 14, 1923 1

"I want people to be able to see it from Wilshire." --Harry Chandler, describing his vision of the Hollywoodland sign 2

Eli P. Clark and "General" Moses H. Sherman were successful L.A. pioneers. Originally from Arizona, the brother-in-laws developed the city's first streetcar lines in the 1890s. Like many of the early founders of L.A., Clark and Sherman had their hands in many pots and shrewdly bought up land near their own street car lines. In 1905, they purchased 640 acres of old ranch land, owned by Julia E. Lord, high above the small town of Hollywood. In 1911, developer Albert Beach paved the road leading up to the land and named it Beachwood Drive. A handful of homes were built along the road, but Clark and Sherman held off on developing their acreage and used it primarily as a granite quarry. In 1916, the natural canyon, where the entrance gate and business district of Hollywoodland would soon stand, was used as an outdoor theater. A production of Julius Caesar, starring Tyrone Power Sr., was staged there to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare's death. 3

By the early 1920s, the time for a large-scale hillside development had finally come. Private car ownership was skyrocketing. Mulholland Highway was in construction and the Hollywood Reservoir was being built adjacent to Clark and Sherman's property, creating a scenic recreation spot. Plans for a new neighborhood in upper Beachwood Canyon were put into motion by an already successful development syndicate that included Clark, Sherman, the L.A. Times' Harry Chandler (who supplied ample free publicity and laudatory coverage through his paper), realtor and developer Tracy E. Shoults (who would die of a heart attack at his office in Hollywoodland in 1923), his successor Sidney Woodruff, and publicist John D. Roche.

On March 31, 1923, the first 107 acres of the foothill subdivision were put on the market. Promising to put the hustle and bustle of "Hollywood at a distance," Hollywoodland took the form of an economically attainable fairyland. 4 A picturesque, kitschy faux-Spanish village of shops was built behind the heavy stone gates. Homes were built in whimsical, precious styles, like English Tudor, California Revival, French Normandy, and Mediterranean. Paths for hiking and riding were cleared through the mountains, and community stables were built. Landscape architect Theodore Payne planted California poplars, blazing stars, wild Canterbury bells, blue lupine, wild heliotrope, wild lilac, wild cherry, mountain mahogany, sumac, lemonade berry, red mahogany, California holly, and California juniper.

Very modern publicity stunts were utilized to sell this throwback hamlet. In July, the L.A. Times told of newsreel and press cameramen filming from "a safe distance" as a granite hill in Hollywoodland was shattered with eight thousand pounds of dynamite. 5 In September, the paper announced the construction of architect John DeLario's demonstration house for the subdivision would be filmed from beginning to end by motion picture cameras. Documenting the birth of this "dignified, half-timber construction of Norman French architecture" (which utilized native rock mined onsite) was undertaken "for the benefit of builders, architects and homeowners." 6 Throughout the development's construction, Mack Sennett's (who had planned to build a mansion on land he owned above the development) bathing beauties posed atop tractors and peaks for stills that were disseminated to media outlets countrywide. But no Hollywoodland ad was more in keeping with the gaudy promotional spirit of the roaring twenties than the gargantuan sign penciled out by publicist John Roche, a former typographer.

Massive signage utilizing the plentiful mountains of California was not a new thing. In 1905, a giant "C", representing the University of California, was erected in the hills above Berkley. In 1922, Hollywood High spirit manifested itself in a giant wood and tin "H" on the hills west of the Cahuenga Pass. Chandler in particular was a huge believer in the importance of signage and emblems as a marketing tool, and quickly jumped on Roche's preliminary drawing. Chandler wanted the letters of the sign scaled to Wilshire Boulevard, the "highway to the sea," and one of the most traveled streets in Los Angeles.

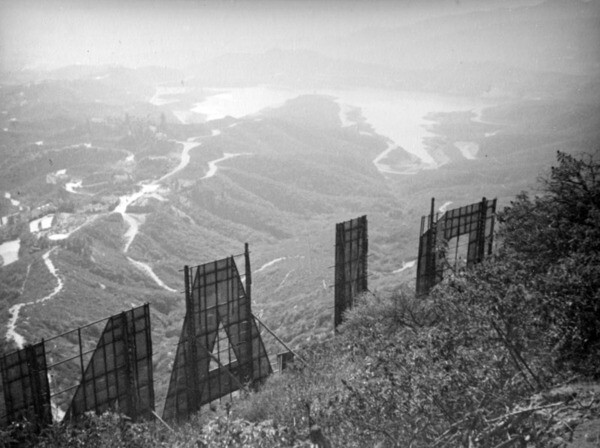

Roche oversaw construction of the sign, which was planned as a temporary advertisement. In mid-1923, workers scaled almost 1700 feet to the ridge just below Mack Sennett's mountain top property. Mules were used to transport the materials for the sign. Made of wood and steel, each 50-foot letter was anchored on telephone poles. The sign was completed in 60 days at a cost of around $21,000. The letters primarily faced east towards prospective buyers in the flats, in the hope that as they sat in a traffic jam, or walked down a crowded street, they would look up and see a better life in the hills, far from "the maelstrom of human existence." 7 The sign was most eye-catching at night, when 4,000 light bulbs outlining each letter lit up in four stages to spell out "Holly," "Wood," "Land" -- Hollywoodland. 8

In December, 1923, Chandler advertised his grandest advertisement in the L.A. Times with some fun cross-promotion. Australian actor Harry Neville took a challenge issued by "L.J. Burrurd, genial advertising manager of Hollywoodland," to drive an Oakland motor car from the Oakland Motor Company up to the "big sign." Under the guidance of Burrud, the car was driven up the trail to the very razor edge of the hogsback that leads upward, with the heavy loose dirt offering but little traction. It took quite a few minutes to get the car up over the worst of the grade -- and then the task of turning it around presented itself. A motley crowd of hill climbers, workmen, salesmen, and curiosity thrill seekers watched nervously until Neville had the Oakland car headed downward, and a cheer resounded from the throng. 9

Soon, the sign was competing for wattage with other signs nearby: one advertising the development of Tryon Ridge, and a neon red sign announcing Outpost Estates. But the "Hollywoodland" sign kept shining brightly, maintained by caretaker and watchman Albert Koeth, "the daredevil handyman," who lived in a small shack behind the "L's" of the sign. 10 For fifteen years, Albert, a recent German immigrant, would scale the letters with 20-watt bulbs stuffed in his shirt, replacing any that had burned out. When Mack Sennett went bust, with his hilltop palace never built, Koeth's only company for many years was the glittering lights of "Hollywoodland" and the illuminations of the city that spread out below.

The Ballad of Pretty Peg

"I am afraid I'm a coward. I am sorry for everything. If I had done it a long time ago it would have saved a lot of pain." --Peg Entwistle 11

The depression slowed the growth of the Hollywoodland development, but the sign stayed up long past its original expiration date, a leftover symbol of the optimistic, boom time of 1920s Los Angeles.

The '20s had also been good to a sensitive young woman named Lillian "Peg" Entwistle. But by the cruel fall night of September 16th, 1932, Peg's luck had run out. Her presumed suicidal jump off the Hollywoodland sign that night would become a legend in later decades, when the sign had acquired a different meaning. Peg became an archetype, an often nameless stand-in for all lost and brokenhearted Hollywood wannabes. As is usually the case, her real story is much more nuanced, infinitely more moving and a great deal more mysterious.

Peg was born in Wales in 1908 into a theatrical family. Her mother seems to have died or left the family early. The motherless girl's early childhood was spent in London. By 1913, she and her father Robert were in New York, where he appeared in several plays. Robert soon remarried and had two sons. In 1922, Robert was killed in a hit and run accident on Park Avenue. Peg's younger brothers were eventually taken to California to live with their Uncle Harold, a theatrical manager and bit actor.

Peg stayed in the east, and by the age of 17 she was studying acting with a respected company in Boston. This petite blond girl, who her brother called "really tiny,"[E! True Hollywood Store; Peg Entwistle] quickly became a well-known working actor, most often cast as a sweet ingénue. Her delicateness and vulnerability endeared her to audiences in New York and Boston, and fans included a young Bette Davis, who is said to have told her mother, "I want to be exactly like Peg Entwistle." 12

Through the years, Peg racked up positive notices professionally, but her personal life fell flat. She allegedly discovered that her husband, actor Robert Keith, had an ex-wife and a child (the actor Brian Keith, later known as the father on TV's "Family Affair"). A huge fight ensued, and it has been reported that Peg was beaten. She and Robert divorced in 1929. In 1932, after a series of Broadway disappointments, Peg headed west to live with her Uncle Harold on Beachwood Drive, a few blocks below the Hollywoodland gates.

Peg's bad luck seemed to follow her to L.A. She scored a role in the play "The Mad Hopes," which had good pedigree -- starring Billie Burke and a young Humphrey Bogart -- but it folded early. Peg next "followed the goblin finger to the studios," when she was put under contract at RKO. But her major supporting role in the film "Thirteen Women" was mostly cut out, and she was released from the studio. 13 She started to save money, telling her uncle that she wanted to return to New York.

She never made it back. On the night of September 16, a morose Peg allegedly told her Uncle Harold that she was going up to the drug store at Hollywoodland Village, and then meet with friends. Instead, she made her arduous way up the winding streets of the quiet neighborhood and then up the unpaved hills...

"...lured apparently by the glittering electric sign with its fifty-foot-high letters. Up the workmen's ladder she went, after leaving her coat and one shoe on the ground. No one will ever know how long she stood on that great letter H but at last she kept her rendezvous with death." 14

One can't help but wonder if Albert Koeth was home that night in his little shack behind the sign. If he was, did he hear anything? If so, it is lost to time. On September 19 the L.A. Times reported:

Almost as bizarre as the woman's death was the manner in which the police came to find her body. Police Officer Crum sat at the telephones at the complaint desk at central station last evening. He picked up the receiver and a woman's voice sounded over the wire. "I was hiking near the Hollywoodland sign today and near the bottom I found a woman's shoes and jacket. A little further I noticed a purse. In it was a suicide note. I looked down the mountain and saw a body. I don't want any publicity in this matter, so I wrapped up the jacket, shoes and purse in a bundle and laid them on the steps of the Hollywood police station." "Now can't you just tell us your name?" wheedled Crum. The woman ceased to speak and Crum heard the click of a receiver. 15

The suicide note signed "P.E." was published, and Uncle Harold soon put two and two together. After claiming the body at the morgue he told reporters, "Although she never confided her grief to me I was somehow aware that she was suffering intense mental anguish. She was only 24. It is a great shock to me that she gave up the fight as she did." 16

Peg's death soon became just another ghost story -- her spirit is said to haunt the sign, leaving behind it a trail of her signature gardenia perfume. It was claimed that the day Peg's body was found, she received a letter from the Beverly Hills Playhouse, offering her the lead in a play where the young ingénue is driven to suicide.

'Ollywoodland, Hollyweed, and Hefner

Dropping the "H" in Hollywood became so important yesterday that the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce offered to spend $5,000 to put it back up ... Representative Davies said his district was sensitive about becoming known as "ollywoodland" 17

By 1939, maintenance funds for the sign dried up. Koeth was forced to move down the hill to Beachwood Canyon, and in his absence the sign quickly began to deteriorate. Vandals snatched the glittering bulbs, the metal of the sign rusted and windstorms caused further damage. In 1944, the cash-strapped developers of Hollywoodland deeded the sign to the city. Around this time the Hollywoodland development ceased to be. All architectural restrictions on the land were lifted, causing a glut of incongruous housing to be built in the canyon. The sign was considered an eyesore by many residents. It was no longer glittering white, but rusted, with pieces including the letter "H" lying twisted in the rocks below.

While the sign itself fell into disrepair, Mack Sennett's old land behind the sign had new purpose. In 1938, 20 acres were bought by TV, radio and broadcasting pioneer Don Lee's company, which had been run by his son, Thomas, since his death in 1934. The mountain was renamed in honor of the departed Don Lee, giving the Hollywoodland sign a new address. Around 1939, a transmission building and transmission tower were built on the land. The 300-foot transmission tower's signal could reach into the city and the valley. The tower and center were later utilized by the U.S. government during World War II and into the Cold War, when it purportedly became a control center. It has been reported that "about 100 feet above the sign is a government compound that claims to be an air rescue training center." 18

At least one man seems to have still found the sign useful during its decline. In 1947 singer Nat King Cole fell in love with the song "Nature Boy," written by one Eden Ahbez. Before Cole could record the future #1 hit, Ahbez had to be tracked down and permission obtained. Ahbez was one of the earliest hippies, embracing oriental mysticism and vegetarianism, donning shoulder length hair and signature rustic robes. Legend has it that Cole's manager finally tracked Ahbez down in a most unusual place: he was living with his wife in a camp below the "LL" of the Hollywoodland sign. In subsequent years other folks embracing alternate life style, and those down on their luck, would take shelter near the sign.

The sign's path was not so illustrious. By 1949 embarrassed 'Ollywood residents wanted it torn down, and in January the city agreed. 19 However, the publicity savvy Hollywood Chamber of Commerce had the decision reversed by promising to pay $5,000 to replace the fallen "H," and tear down the "land." They also promised to provide bonds for its maintenance, and insurance in case of liability suits and damage. "Hollywoodland" was no more. Within a few months the sign now read, "Hollywood," officially advertising the city and movie business.

The sign quickly fell into disrepair again. It was occasionally repainted, and superficially restored with pieces of metal and wood. Beachwood Canyon residents, fed up with the incessant parties at the sign and increasing tourist traffic, fought preservation efforts with banners reading "death to the sign." 20 They got their wish temporarily, when a coat of green primer caused the sign, which was designated a Los Angeles historic monument in 1973, to seemingly vanish into the hills.

While the sign itself deteriorated, its importance as an icon slowly grew. The decision to drop the "land" had been a smart one. The L.A. of the '60s and '70s was discovering its history. As the old studio system fell apart, film history grew into a discipline of study, and pop art made advertisements things of value. A series of performance art pieces during the 1970s sealed the sign's status. On Jan 1, 1976, a Cal State Northridge art student, Danny Finegood, scaled the mountain in darkness with a friend. Together they hung huge pieces of fabric over the letters to spell out "HOLLYWEED," in celebration of relaxed marijuana laws, for a class project. He got an A grade. He would repeat this piece several times in the next 20 years, spelling out "Holywood" upon the Pope's visit to L.A., and "'Ollywood" in reaction to the Iran-Contra scandal. Others would follow suit, including fans of local sports teams. Artist Ed Ruscha would also create a series of iconic paintings of the sign, which he claimed to have mainly used as a smog indicator from his studio window.

Periodic refurbishment of the sign continued until the late 1970s, when it was finally admitted that the sign needed to be completely replaced. In 1978, money was finally raised to rebuild the sign. A group of Hollywood lovers, including Hugh Hefner, Andy Williams, and Gene Autry, donated enough money to construct each letter in the new sign. The rocker Alice Cooper even contributed $27,000 to build the second "O" in honor of his recently departed friend, Groucho Marx.

And so in August of 1978, the old sign was torn down, its telephone poles ripped out of the earth. In their place were 20-foot steel beams, drilled into the earth and cemented in concrete. The old patchwork letters were replaced with sturdier ones made of corrugated steel coated in white enamel. The sign was finished within three months to much ballyhoo.

The original sign was thought to have been lost, until it appeared on eBay in 2005. It was sold for $450,000 by Dan Bliss, who apparently bought it from nightclub entrepreneur Hank Berger, who had bought it from the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. It is currently owned by Minnesotan artist Billy Mack, who has refurbished the "H," and painted pictures of iconic Hollywood stars on it. He claims you can still see dings left long ago by Albert Koeth, after he drove his car into the bottom of the letter.

And what of the new sign? As a potential "soft target" for terrorists and teenagers everywhere, it is now protected by infrared cameras, a satellite view, and 24 hour surveillance from Griffith park rangers. Hugh Hefner came to the rescue of the sign again in 2010 when he, along with a group of Hollywood heavyweights, raised $12.5 million for the purchase of 138 acres of land to the west of the sign to "save the peark," which had been put on the market to sell as residential parcels. 21 This would have destroyed the unobstructed, clean view of the Hollywood sign.

And who wants to obstruct the view of the Hollywood sign? Who doesn't want to believe that dreams can come true, that magic is attainable, that Hollywood is the promised land? The history of the sign almost seems to confirm all these crazy reveries. If a temporary advertisement for a housing development can become a worldwide icon representing an industry and life's yearning, surely a nice girl from North Carolina, and her three best friends, can make it in Hollywood, too.

Additional Photos by: Hadley Meares and Cat Vasko

_____

1 "Bonds assure new highway" Los Angeles Times, October 14, 1923

2 Leo Brady, "The Hollywood Sign, Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon" Yale University Press, 2012

3 Mary Mallory "Images of America: Hollywoodland" Arcadia Publishing, 2011

4 Leo Brady, "The Hollywood Sign, Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon" Yale University Press, 2012

5 "Giant Blast shot off in subdivision" Los Angeles Times, July 19, 1923

6 "Will film building" Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1923

7 Leo Brady, "The Hollywood Sign, Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon" Yale University Press, 2012

8 Gregory Paul Williams, "Hollywoodland, established 1923" Papavasilopoulos Press, 1992

9 "Hollywoodland electric sign reached by car" Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1923

10 "Hollywoodland" Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1972

11 "Girl leaps to death from sign" Los Angeles Times, September 19, 1932

12[Chandler, Charlotte (2006). The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis, a Personal Biography. Simon and Schuster]

13 "Suicide laid to film jinx" Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1932

14 Ibid.

15 "Girl leaps to death from sign" Los Angeles Times

16 "Suicide laid to film jinx" Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1932

17 "Hollywood sensitive about dropped H on hillside sign" Los Angeles Times, January 11, 1949

18 "Hollywoodland" Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1972

19 "Ruling asked in case of Hollywoodland sign" Los Angeles Times, January 25, 1949

20 Leo Brady, "The Hollywood Sign, Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon" Yale University Press, 2012

21 "Hollywood sign temporarily covered with 'save the peak'" Los Angeles Times, February 12, 2010