Masculinity, Femininity, and Asian American Basketball in 20th Century California

"I'm not particularly proud of it, but over the past two weeks, I've exchanged countless e-mails with my Asian American friends about how the only way the Jeremy Lin story could possibly be better is if he talked like Nas and released a dis track on Tru Warier Records," wrote Jay Caspian Kang in early 2012. Kang, a novelist and editor at Grantland, drafted a series of articles reflecting on Bay Area native Jeremy Lin and his effect on Asian American identity. For Kang and other Asian Americans, Lin's 2012 meteoric explosion meant something in terms of broader representation and pushing back against stereotypes. "All of us have shared stories, without a hint of modesty or shame, about getting choked up while watching Knicks games," admitted Kang, whose columns touch on issues of masculinity, nationality, and, obviously, race.

Lin's ascension to superstar status, his struggles in his first year at Houston, and his stabilization as a quality, above average point guard this year, have played into typical American narratives regarding sports. Even during his 2013 struggles, the title of an April 2013 article in the New York Times pretty much summed it up: "From Phenom to Everyday NBA Player." Lin had achieved "the unremarkable," noted journalist Jere Longman, by becoming a solid everyday player.

While Longman's piece does adopt the age old narrative frame by which a player's ethnicity, race, gender, or sexual orientation no longer dominates headlines, but rather his or her solid play proves them a reliable professional, it also gets at a larger point regarding athletics: sport need not revolve around an exceptional talent like Lin. Rather, like the amateur Japanese American baseball leagues of the 1920s and 1930s, which produced zero professionals but nonetheless stitched communities together, the Asian American basketball leagues of Northern and Southern California provided cultural capital, community, and in the case of Filipino Americans, transnational ties to their homelands.

While the complexity of race, ethnicity, and immigration may complicate the material and symbolic meanings of Asian American basketball leagues, they also give shape to the unique histories of each ethnic group living under the flattening designation of "Asian American." The sport also offers insight into gendered racial stereotypes imposed upon and rejected by Asian American men and women. Accordingly, a look at a media icon like Jeremy Lin, while paying careful attention to Asian American leagues at the grassroots level, provides important clues into how sport participation allows these various communities create their place in the national fabric.

Asian American basketball leagues have existed in California since the early 1900s, often reflecting particular ethnic populations of an area. Over time most have gone from exclusively Chinese or Japanese American, to more broadly Asian American. While there have been controversies regarding race and ethnicity restrictions, many leagues allow for much broader demographics. "Today, we also have Chinese, Koreans, [Filipino], and more," said Russ Hiroto, commissioner of San Jose's Japanese Community Youth Services (CYS) and former SoCal basketball participant himself. "In fact, it's more realistic to describe the JB (Japanese Basketball) program today as AB 'Asian Basketball." 1

With that said, often particular Asian ethnicities predominate within a league. For example, in the Pacific Youth League (a pseudonym used by Sociologist Christina Chin in her research to protect participants in Southern California leagues), which began as a volunteer organization in the 1960s, over half the players hail from Japanese American backgrounds. In the Asian Ballers Syndicate (ABS) of Orange County, in which Filipino Americans serve as the largest constituency participating in play, quotas exist for non-Asians, but what constitutes Asian stretches from Japan to Pakistan. Similarly, leagues on the East Coast, such as Atlanta's Asian Baller's League (ABL) follow similar regulations. 2

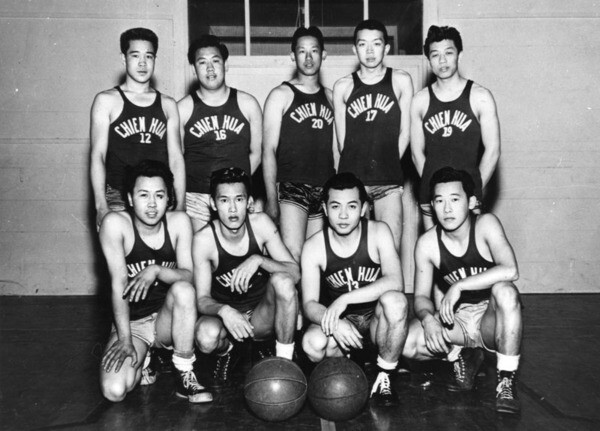

Chinatown Leagues

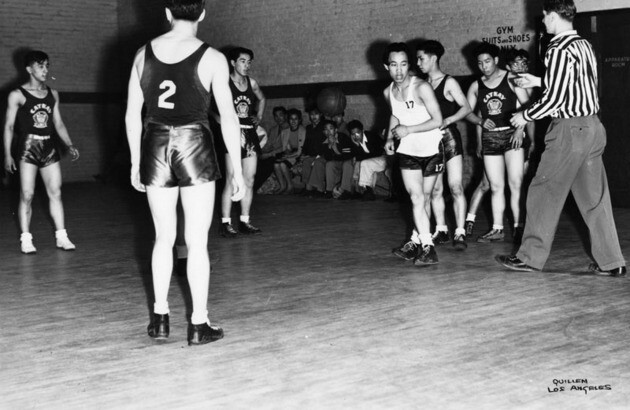

While such leagues seem to be in vogue today, they originated in Progressive era San Francisco. The city's Chinatown of the 1930s and 1940s, notes historian Kathleen Yep in her 2009 work, "Outside the Paint: When Basketball Ruled at the Chinese Playground," witnessed hundreds of Chinese American youth running the floor and competing for teams with names like Nam Kus and the Boy Scout Troop Three, in leagues like Wah Ying and Chi Hi. 3 The Hong Wah Kues, a Chinese American team consisting of working class San Franciscans, barnstormed America and Canada, playing other professional sides like the famous Harlem Globetrotters. 4 Indeed, Yep demonstrates that Jeremy Lin wasn't even the first Asian American to grace the court of the legendary Madison Square Garden, but rather San Francisco's William Woo Wong. As a member of the 1949-1950 University of San Francisco's NIT squad, Wong beat the former Knick to it by over 50 years. 5

While perhaps forgotten today, Wong's achievement demonstrates that sport and agency often bring contradictions. "Mainstream communities viewed basketball as a way to assimilate second generation Chinese Americans into the American 'melting pot'," notes Yep, "while many second generation Chinese Americans simultaneously used basketball to build community and assert ethnic pride." 6 One must also remember, as positive as such examples might be, sport often comes with its own structural inequalities and heteronormativity. The Hong Wah Kues, which certainly inspired Chinese American youth and served as minor celebrities in ethnic communities, were managed and run by a white accountant from San Francisco, while their promotional literature trafficked in the most essentialistic aspects of Orientalism. Newspaper reports admired their basketball acumen, but continued to describe them as "the boys from the land of Chop Suey," or worse, "the chinks flashed a snappy and deep passing attack." 7

In some cases, efforts to subvert popular tropes regarding Asian American masculinity have resulted in the creation of new internal discrimination. In his study of Asian American basketball leagues in Atlanta, Stanley Thangaraj points out that efforts by South Asian American male participants to undermine popular gender stereotypes sometimes supported "conceptions of masculinity and racial identity that preserve conservative regimes of race, gender, and sexuality." 8 To put it more simply, in an effort to broadcast their own masculinity, some players resorted to homophobia or misogyny and their own forms of racial stratification. While differences exist between South and East Asian cultures, and the context of Atlanta differs markedly from that of Southern California, the observation remains constructive.

To this end, basketball has not been exclusively the province of men, in San Francisco's Chinatown or elsewhere. The Mei Wahs of the 1930s symbolized not only agency by working class Chinese American women, but also epitomized the demographic shifts cascading over Chinatown. During the 1920s and 1930s, Chinese families found ways around exclusionary immigration laws through "paper sons and daughters," more or less Chinese-born citizens immigrating to the U.S. claiming to be the offspring of Americans.

In 1935, the Mei Wahs took the San Francisco Rec League title. The English language Chinese Digest, founded by a trio of second generation Americans, praised the team in a 1936 cover story that touted them as being as "good as any boys." 9 In 1937, they helped to form Chinatown's first female basketball league. The 1938 championship game drew over 200 spectators.

A decade later, Helen Wong led the St. Mary Saints to championships in 1947 and 1949 in the city's predominantly white Catholic Youth Organization league. The sister of the aforementioned Woo Wong, Helen drew effusive comments from the San Francisco Chronicle: "We know now why the kids in Chinatown were telling us, 'Wait until you see Willie "Woo Woo" Wong's sister, Helen," exclaimed the paper. 10

Japanese American Basketball SoCal Style

Japanese Americans in Northern and Southern California also embraced the sport. Though initially enthralled by baseball, they eventually adopted basketball, in part due to earlier conditions in Japantowns across the West Coast where cramped spaces and frugal lifestyles made the sport more accessible than baseball. During internment, basketball also served to calm nerves for internees. Jamie Hagiya, a former NCAA and University of Southern California star and professional player, related her own parents' story to journalists in 2012. Moved to Wyoming and Arkansas, her parents developed a love for the sport amid the tragedy of internment. "Even though they had everything taken away from them, they always kept a positive attitude, and sports was a huge way for them to get through those days," she told Colorlines in 2012.

One of the first and most prominent JA leagues, Friends of Richard (FOR) formed in 1959 in memory of Richard Nishimoto, who died at the young age of 18. Beginning with 15 members and eight officers, FOR started as a service organization and baseball team, often performing local chores such as house painting or yard work. After completing these tasks, FOR members played baseball and picnicked. Even today, teams often hold potlucks right outside of the gym after their games.

In Orange County, the Santa Ana Youth Organization (SYO), long helmed by local legend Jesse James, organizes dozens of teams annually while also holding clinics for younger players. Changes in demographics have facilitated its growth. Between 1990 and 2000, California's Asian American population increased by 38%; today officials estimate that nearly 14,000 Japanese Americans in Southern California play regularly in club and league tourneys. "These leagues," observed former Cal State Los Angeles head basketball coach Dave Yania, "provided an opportunity for teams of Japanese heritage to compete." 11

They also forge friendships and community that carries into adulthood. "I actually knew almost every Japanese American guy at UCLA my freshman year because we'd played against each other in the basketball leagues," filmmaker Tadashi Nakamura told journalists in 2012. According to Nakamura, Japanese American basketball leagues had become institutions equal to those associated with religion and language. "For people my age, fourth generation Japanese Americans, [basketball] is, in a weird way, the main cultural hub and the one commonality that most Japanese Americans have with each other."

Sociologist Christina Chin, an expert on Asian American identity and sports, and co-editor of the forthcoming anthology Asian Sporting Cultures, notes that few spaces exist for Japanese American youth to "hang out" with other young Japanese Americans. With the highest rates of out marriage among Asian Americans, and distinctly fewer immigrants today than their Chinese, Filipino, or Vietnamese counterparts, many Japanese Americans worry that cultural assimilation might come at the expense of lost heritage and sense of identity.

"Our neighborhoods are smaller, Japanese American church attendance is down," Rebecca Chiyaku King-Oriain, then-sociologist and San Francisco resident, told the Los Angeles Times in 2000, "but this one thing has endured." Basketball, she argued, much like Nakamura, had taken on a deeper cultural meaning.

Gendered Basketball

Of course, discussing Asian American basketball without further discussing gender would be a mistake. Though men in each ethnic group endured emasculation in different ways, generally, Asian men's sexuality and masculinity has long been portrayed as feminine, licentious, and in some cases asexual. At the turn of the twentieth century, immigration and other federal officials conflated Chinese men with dependency, a charge that equated them with shamefulness and perversity. Unable to marry, due to laws like the 1875 Page Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and barred from land ownership, Chinese men remained in this state of dependency due to the fact that they could neither become property owners or husbands. Many Americans had no problem imposing similar racializations on other Asian/Asian American communities, already present and those that would come later. 12

As Yep and Chin both point out, basketball offered a space to assert qualities associated, rightly or wrongly, with masculinity, and publicly reject their racialization. The Chinese Playground of San Francisco's Chinatown, for example, provided Chinese American athletes a space in which they could be "assertive -- even aggressive -- visible and celebrated." 13

Eventually, WWII and the Cold War helped alter immigration regulations and popular perceptions of Asian Americans, morphing into what has famously become known as the "Model Minority" stereotype. In the postwar period, as Glen Omatsu points out, this stereotype has cast Asian Americans in the role of "best minority," thereby demoting less successful groups. Others like Robert G. Lee have pointed out that due in part to Cold War pressures, portrayals of Asian Americans as "politically silent and ethnically assimilable," unlike their Chicano and black counterparts, grew in the postwar era. For Japanese Americans, Chin suggests, basketball helped construct a counter narrative to popular representations and perceptions that often depicted Asian Americans, particularly men, as nerdy, politically inactive and passive. "While young Japanese American boys and girls are learning the fundamentals of basketball," Chin points out, "they are also actually constructing and negotiating notions of race and gender within their sports leagues."

As with earlier examples in San Francisco, Asian American basketball not only provided men with a chance to challenge stereotypes regarding their masculinity, it also enabled female players to do the same, in many ways undermining sexism in dominant culture and within their own ethnicity. "Their bodies," Yep argues, "furnished a way to develop and articulate a sense of self respect as a member of a group marginalized by both the mainstream and Chinese communities." 14 Undoubtedly, the Mei Wahs' aggressive, fast, physical play of the 1930s contrasted sharply with sporting manuals that suggested women should not exert themselves too strenuously on the court. They played a tough, elbow driven style that former Mei Wah Josephine "Jo" Chan proudly admitted veered into the very physical. "As I always say, [teammates] Mary and Rachel, they play dirty. They know how to use their elbows and push," she reflected years later. Such physical play and exertion would make them too masculine, as society told women at the time. As Yep argues, "rules at the time forced women to act and move in accordance with societal norms of male power and privilege." 15

In 1930s Chinatown, in which the arrival of "paper daughters" and high birth rates among Chinese women altered the dynamics, from nearly exclusively male to a more equal division between genders, the Mei Wahs helped to craft their own female identities through sport. Cultural difference might have helped. Though American women's basketball of the 1930s imposed dominant, patriarchal ideas regarding biological difference between men and women, in the context of Chinese Republicanism of the period (1912-1949) and communist nationalist ideology, the sport represented a key aspect of an independent nation. "Women's basketball in China testified to women's ability 'to hold up half the sky,'" notes Yep. While some Chinese immigrants did view the Mei Wahs as acting like "loose Caucasian women," others may have absorbed the nationalist ideology. In any case, the Mei Wahs reoriented ideals of femininity to their own ends, and they represent only one path among numerous other avenues taken by Chinese women of their day to stake a level of independence and claim to an identity.

Similar dynamics continued to play out in late twentieth century metropolitan Los Angeles. Asian American women in Southern California, particularly those of Japanese descent, have deployed the sport as a means to negotiate gendered and racialized identities. Chin, who spent 18 months as a participant observer in the Pacific Coast League of Southern California, emphasizes this in her field work. "I think a lot of people underestimate Asian basketball players," one 12th grade girl told Chin, "because when you look at them, and especially women, they're shorter, skinny, a lot of people don't really think they could muscle up anyone." Jenn, a freshman at a private California university, admitted she and her friend enjoyed playing pick up ball against "tall white guys" because "it's fun when we go there and we're dribbling around them and scoring all the time." Some parents see more value in basketball for their daughters than other activities. Nadia, a third generation Japanese American, preferred her daughter play basketball over hula lessons. "I want her to be scrappy -- not just a pretty dancer."

In fact, on average, Asian American basketball leagues produce far more high school and college female players than males. Now and then the occasional elite talent develops. The former USC star, Hagiya, developed her skills playing in Southern California Japanese American leagues. Starting at age four, Hagiya never looked back and ended her college career in USC's all time top ten for assists, games played, and most three point field goals made. Orange County native, Natalie Nakase, a former JA league player and three time captain at UCLA, became the first Asian American to play in the National Women's Basketball league and to coach in Japan's top tier men's professional league. Nakase has made it no secret that she harbors bigger dreams. "My goal is to coach in the NBA," she told journalists in 2012.

When Jeremy Lin exploded for a brief few weeks in 2012, it galvanized Asian Americans. While some might argue that Lin's current, more quotidian but successful existence means more than his ephemeral rise two years ago, such views only come from a place of "privilege," suggests Kang. "If you don't need to scrape out role models wherever you can, if you can look at the spectrum of public figures and see plenty of people who could have been you, then you can afford to be objective and practical about the lot of them," he reflected. "You can quietly laud your heroes."

Undoubtedly, Kang has a point, but nor should Lin or anyone else obscure the complex, deep, and varying relationship's that Asian Americans carry with basketball. Even if Lin never participated in Asian American leagues, their existence and persistence in earlier decades created a space for Lin, Hagiya, Nakase, and other players not only in college and professional ranks, but squarely in American culture.

_____

1 John Sallmon, "JA Basketball Evolves, but not Elitist Cult, Experts Say", Nikkei West, December 25, 2013. 5,12.

2 Stanley Thangaraj, "Competing Masculinites: South Asian American Identity Formation in Asian American Basketball Leagues," South Asian Popular Culture 11.3, pgs. 243-255

3 Kathleen Yep, Outside the Paint: When Basketball Ruled at the Chinese Playground, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009) pg. 6.

4 Ibid. pgs. 38-40

5 Ibid. pg. 15.

6 Ibid., pg 3.

7 Yep, Outside the Paint, pg 46.

8 Stanley Thangaraj, "Competing Masculinites: South Asian American Identity Formation in Asian American Basketball Leagues," South Asian Popular Culture 11.3, pgs. 243-255.

9 Yep, Outside the Paint, pg. 74.

10 Ibid, pgs. 65, 102-3.

11 Paul Macleod, "A Community of Basketball Going Strong", Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2001.

12 Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth Century North America, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), pgs. 28-29.

13 Kathleen Yep, Outside the Paint, pgs. 6-7.

14 Ibid, pg. 75.

15 Ibid. pgs. 69 - 70.