Whittier Narrows Parks: A Story of Water, Power and Displacement

In Partnership with the South El Monte Arts Posse

"East of East" is a series of original essays about people, things, and places in South El Monte and El Monte. The material traces the arrival and departures of ethnic groups, the rise and decline of political movements, the creation of youth cultures, and the use and manipulation of the built environment. These essays challenge us to think about the place of SEM/EM in the history of Los Angeles, California, and Mexico.

_____________________________________________________________

A stroll through Whittier Narrows Parks is never anything less than a walk through many worlds. On any given day, the scent of carne asada barbeques wafts on a breeze that is suddenly interrupted by the scent of sunblock from a runner in full stride. The sound of buzzing model airplanes drawing figure eights above the canopy of trees is punctuated by the shots from the shooting range. Weekends are filled with rowdy soccer games and families flocking from distant corners of Southern California for reunions. They meet with wide-armed hugs and dance on grass to their favorite R & B songs from portable sound systems.

Located along both sides the Pomona Freeway, Whittier Narrows is one of Los Angeles County's largest parks at 1,492 acres. Not only is this network of parks part of the daily landscape for locals, but also a landmark in the memories of many generations. It is a site of layered histories in a struggle between the natural and built environment, California water politics, and the uprooted communities that once called this region home.

So how did a working-class neighborhood in drought-parched Southern California become the home for this park?

The answer lies in the story of Whittier Narrows Dam. It is the story of how unprecedented federal money and intervention made enormous transformations on the landscape, often at the expense of the poor and marginalized, and in favor -- even at the behest of -- large and entrenched interests. The California environment that so many cherish -- including the Whittier Narrows nature reserve -- is the result of those changes, for better or for worse.

For as long as humans have inhabited the San Gabriel Valley, Whittier Narrows has been important for its water. The narrows is a gap in the mountains that make up the southern edge of the valley, and is the site of the confluence of the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel Rivers. The geology of the hills is mirrored underground, where an intrusion of bedrock forces groundwater up to the surface.

Manuel Martínez, a former resident of Canta Ranas, one of the displaced communities along the Rio Hondo River, has distinct memories of the taste of these waters that supplied his family's well: "In our well the water was delicious." His family migrated from Michoacan, Mexico, in 1939 to a rustic house in the unincorporated area along the river, where they dug their own 6-foot well.

The rivers and groundwater formed large marshes, home to fish, birds, and mammals where, prior to Canta Ranas or the La Mision barrio, Kizh-Gabrieleño Indians once lived and hunted. It also provided easy access to irrigation for the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, established in 1771 by Spaniards. That is, until the river flooded out the Mission in 1776 and was relocated to its current home in San Gabriel.

The abundance of water made El Monte an attractive site for agriculture throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, when it was home to a growing population and a wide expanse of walnut, citrus, and other farms. Large industrial farms attracted Mexican migrants, like the Martinez family, and the riverside became a popular site for swimming, recreation, and parties for people from East L.A.

At the same time, Whittier Narrows fell under the gaze of Los Angeles area city officials, hydro-engineers, and business interests, who determined that the Los Angeles basin's rivers and groundwater could -- and should -- be dammed, channelized, diverted, and otherwise controlled. The impetus came from a number of factors. Los Angeles is in a desert climate. Annual rainfall is low, but it tends to come in sudden torrents, which overwhelm the arid ground's ability to absorb them and produce flash floods. Urban sprawl exacerbates the problem, by paving over ground and further reducing its ability to absorb water. Moreover, it places buildings, infrastructure, and people in the way, raising the stakes and consequences of floods. Destructive floods in the 1910s, '20s and '30s heightened the need for flood control in the Los Angeles basin. Yet, this was also a time in which the collective wisdom held that rivers -- and the environment at large -- were there to be altered. It was an era when "water conservation" meant building dams and irrigating, and "wasting water" meant allowing rivers, lakes, and aquifers to burble away untouched in their natural state.

Indeed, at the time water all across the West became the object of a unique form of hydro-engineering hubris, a sort of Manifest Destiny of water. Marc Reisner, in his classic book "Cadillac Desert," called these "the Go-Go years" -- decades in which no project was too big or small for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (tasked with managing irrigation projects) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (in charge of flood control and navigation, although in reality the two agencies frequently competed for the same types of project). While visionaries since John Wesley Powell viewed water and irrigation as the key to settling the U.S. West, the magic ingredient finally came during the Great Depression, when FDR's New Deal poured previously unimaginable amounts of money into Western water development.

Projects like the iconic Hoover Dam are part of an American pantheon of technological success stories. Millions have been struck in awe by the dam, and others, like Glen Canyon and Grand Coulee, whose mass and engineering magnificence seem to be outsized monuments to the American will. But as Reisner shows, there is a dark side to these developments. Their direct environmental effects -- harmful enough -- are dwarfed by the complications caused by the settlement by millions of people in what are essentially desert areas -- swimming pools, fountains, citrus groves, and lush golf greens notwithstanding. Some 40 million people depend on the Colorado River alone for all of their water needs. The consequences of this dependence are becoming more and more apparent, as California faces the worst drought in memory, with no sign of relief in the near future.

Moreover, many irrigation projects benefited entrenched interests instead of the everyday people whose livelihoods they were initially meant to protect. Cheap irrigation water from financially dubious projects turned into an enormous taxpayer subsidy to large landowners and some of the nation's richest oil and insurance companies, who snatched up cheap land as a tax dodge and sometimes benefited from federal farm subsidies as well.

The construction of Whittier Narrows Dam lies in this context of runaway water infrastructure. Yet in some ways, it is an exception to the rule, and a significant success story for the ability of local everyday people to have their voices heard in government. As Sarah S. Elkind tells in her book, "How Local Politics Shape Federal Policy: Business, Power and the Environment in 20th Century Los Angeles," the Whittier Narrows Dam story is one time when determined local voices managed to shape -- at least somewhat -- the development of water infrastructure.

A dam at Whittier Narrows was first proposed by the City of Long Beach in 1920, as a means to secure a city water supply independent from Los Angeles. When that need became mooted by the proposal for what became Hoover Dam, the proposed dam at Whittier Narrows fell under broader plans by the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, an agency tasked with managing a total-basin scheme for river diversion, harbor protection, and flood control.

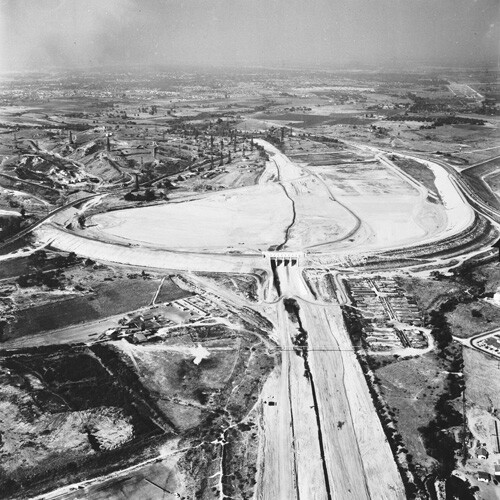

Plans for the dam were in limbo until 1936 when, as part of the New Deal, Congress passed the Flood Control Act, turning oversight of flood control on all rivers to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps included the Whittier Narrows dam in a 1938 plan to redevelop the San Gabriel River, which gained higher priority following a devastating flood in March of that year. The plan would see a dam at Whittier Narrows with a flood control basin and recharge gallery directly above it. This meant that sudden rainfall would be controlled in a reservoir created by the dam, where it would slowly percolate into the underground aquifer.

The problem was that the site of the proposed basin was home to thousands of people, several school districts, a number of farms, railroad tracks, oil wells, and an Audubon Society bird sanctuary (the precursor to today's Whittier Narrows Nature Center). Concerned people in El Monte formed the El Monte Citizens Flood Control Committee to oppose the plans for the dam. They enlisted James Reagan, the former director of the Los Angeles County Flood Control District (who had resigned in disgrace following the collapse of a canyon wall during construction of the Twin Forks Dam in the San Gabriel river and a bribery scandal involving the company overseeing its construction), to propose an alternative to the dam. They also counted on the support of El Monte's congressional representative Jerry Voorhis, who received hundreds of letters opposing the dam, and advocated for Reagan's alternative in Congress.

The El Monte Citizens Flood Control Committee would fight the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and supporters of the dam through the 1940s. As Eskind shows, this was not a fair fight. Technically speaking, the Corps was beholden to local interests: only civic groups, not the Corps itself, could propose and initiate plans for a dam. However, the Corps was extremely selective in which local groups it would listen to. It consistently brushed aside citizens in El Monte, while pointing to the support of the Long Beach Chamber of Commerce, the LACFCD, and other downstream interests. People in El Monte felt that the Corps was pandering to large construction companies, oil companies, and the rich and ignoring the plight of small businesses, everyday people, and the poor. These suspicions were confirmed when the Corps gladly modified the plans for the dam to protect Union Pacific railroad tracks, oil wells, and the Audubon preserve, after they voiced their concerns.

In spite of the opposition, plans went ahead, and were only detained when Jerry Voorhis blocked Congress from appropriating funds to build the dam in 1946. He proposed an alternative dam a mile downstream, which the Corps rejected as too expensive. The opposing sides were entrenched: the locals who would be affected by the dam, who claimed it was too expensive, too harmful to local ways of life, and pandered to big industries instead of small farmers and businesspeople; and downstream and coastal municipal governments, chambers of commerce, and business interests who said the dam would protect an enormous number of people and construction while only affecting a few thousand in El Monte.

The stalemate dragged on until 1947, when Congressman Richard Nixon -- who had replaced Voorhis in 1946 -- stepped in and convinced the Army Corps of Engineers to construct Voorhis's "Plan B" -- the dam a mile further downstream. Last ditch efforts to block the dam, led by San Gabriel Valley irrigation companies, failed, and construction began in 1950 -- some twenty years after the dam was first proposed. The "Plan B" was less disruptive than the Corps' original plan, but thousands of people were nonetheless forced to move to make way for the dam and the spreading grounds (areas where flood water can percolate back into the underground water table). As Manuel Martínez recalls: "All they told was that everybody had to get out." They were never compensated. "We probably could have sued for that."

The victory for El Monte was bittersweet. El Monte citizens were successful in altering the original plans for the dam, meaning fewer people had to move, and the Audubon sanctuary was preserved. It was passed to the county's Parks and Recreation department in 1970 and has become Legg Lake and the Whittier Narrows Nature Center. Yet the compromise still displaced more than 2000 people and 560 homes, including much of the Temple School district's population.

Robert Irwin, born in Whittier in 1935, also remembers the construction of the dam, and creation of Legg Lake, as disruptive. "The state came in and built Legg Lake. They ripped everything down."

As Eskind writes, the process by which Whittier Narrows was created was not exactly undemocratic: a majority of people in the region supported it, and the dam works as it was supposed to. But the way it was finally approved left a lot to be desired. The Corps' consulting of the public was not even or inclusive, but rather highly selective, to bolster support for a project the Corps wanted to construct. Moreover, while El Monte citizens ultimately shaped the final plans for the dam, they never gained enough political traction to affect the overall policy of flood control and river alteration for the Los Angeles basin.

With the passage of time, the Whittier Narrows controversy has faded somewhat in memory (except for those, like Manuel Martínez, who were displaced by the dam). Whittier Narrows today is a community gem. "It was a wonderland for children," recalls Dana Law, who moved to El Monte as a boy in the early 1960s. The dam and its spreading grounds has ensured the survival of some 400 acres of forest, lake, trails, lawns, and soccer fields, a rare natural site in the greater city, an important place for recreation, gathering, and having fun, and a living link to the memory of El Monte's agricultural past, as well as the Kizh-Gabrieleño oral tradition that recalls the area as a water-filled natural paradise.

Ironically, the conflict over Whittier Narrows has been revived in the controversial plans for the San Gabriel River Discovery Center, which opponents claim is too big, too expensive, too destructive of natural habitat, and the brainchild not of local people but of large, outside interests. As Andy Salas, son of Chief Ernie Salas of the Kizh-Gabrieleño Indians, says, "This big eraser called 'progress' is going to come in and take away the last native lands."

Once again, Whittiers Narrows reflects broader questions about people and water in the West. Now that we've created this world through water, how do we sustain it? For whom? To what ends? Whose voices will be heard in the process? While the problems may be familiar, the answers remain uncertain.