Miracle on Wilshire Boulevard: From Growing Beans to Counting Beans In a Shopping District That Beat the Odds

By Sandi Hemmerlein

Editor's note: Last night (7/10/18) 10 That Changed America featured Wilshire Boulevard on its 10 Streets That Changed America episode. We asked Sandi Hemmerlein to further the conversation and share with us what makes Wilshire Boulevard so remarkable.

Once an undeveloped, dusty stretch of land near the tar pits, Wilshire Boulevard was initially deemed “unlivable.”

Except, of course, if you were a bean.

To most in the 20th century aughts, Wilshire seemed good enough only to house farmland (mostly beans and dairy), airstrips, and oil fields—but developer A.W. Ross was determined to create a commercial district out of it.

And so was born our Miracle Mile, an apt moniker considering all of the obstacles that could have entirely impeded its development.

We may now call it “Museum Row,” but in its infancy, Miracle Mile was known better as the “Fifth Avenue of the West.”

`

Among the early standout buildings along Wilshire Boulevard was the eight-story Wilshire Tower, a zigzagged and Streamline Moderne monolith. Its ground-level storefronts were occupied by two Downtown LA retailers: Silverwoods and Desmond’s.

Designed by architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood, the tower (colloquially also known as the Desmond’s Tower) anchored Wilshire Boulevard just four blocks west of La Brea and, and as some might say, paved the way for Wilshire’s expansion west to Beverly Hills and east towards Downtown.

At the time, if you headed eastward to the area we now know as Wilshire Center, you would’ve eventually hit the more residential stretch of the road. Drivers mostly passed through it on their way east to the most established shopping district of the time—Dowtown, or west to the Miracle Mile

But in 1929, Bullocks Wilshire changed all that, when it began catering to car culture more than the other shops, with its street-facing window displays, eye-popping edifice, and ample parking spaces.

In fact, the "front" entrance of the department store was technically in the rear of the building. Instead of pulling up front, shoppers drove up to a motor court (porte cochère) in back to drop off their cars with a valet who’d park them at the adjacent lot.

And there was plenty at Bullocks to keep one at its flagship location on Wilshire, eventually making it a destination rather than a passing impulse.

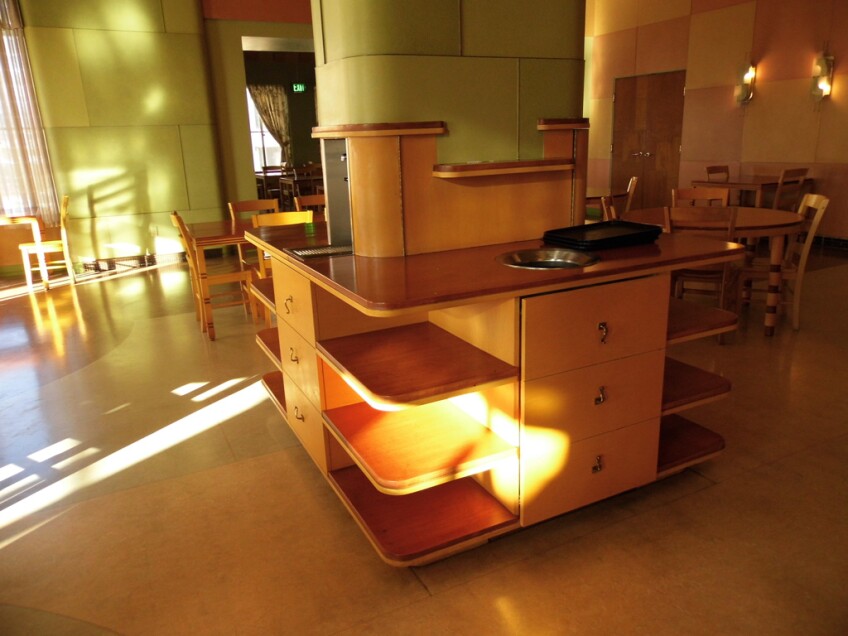

If it wasn’t the shopping, perhaps it was the building. Most who entered were dazzled right away by the Central Hall, a grandiose entryway reminiscent of the Empire State Building lobby, but decorated with an ostrich feather Christmas tree during the holidays.

With architect John Parkinson’s brilliant Art Deco design, no two rooms looked the same, from the Streamline Moderne style near the gift-wrapping desk to the Mayan Revival of the menswear department.

Throughout this “cathedral of commerce,” each department provided unique sanctuary from the bustling car culture burgeoning in LA. In fact, "live mannequins" would model haute couture from top designers like Chanel in period rooms that transported visitors to Marie Antoinette's boudoir in the Palace of Versailles, Paris, or even China (by way of France, of course).

Perhaps in the nascent days of “retail therapy,” customers lingered even longer to admire the art at Bullocks—starting with the "Spirit of Transportation" ceiling fresco by Herman Sachs at the carport and continuing to the "Spirit of Sports" mural by Serbo-Croatian artist Gjura Stojano in the women’s sportswear department.

But what people who shopped at Bullocks seem to remember the most is the Tea Room—a 1929 predecessor to the modern “food court” in a shopping mall—that provided sustenance and a rest stop to shoppers who’d worked up an appetite.

Ross’ ingenuity and laser focus on “windshield shopping” rather than window-shopping on foot created a boon for retailers along Wilshire.

Attracting automotive passers-by with stunning architectural frontage (at the time, that meant Art Deco facades all the way down the line) and eye-catching signage was something we’d continue to see later along cross-country routes like Route 66, but in those days, it was a groundbreaking concept.

But Ross didn’t stop there. He actually changed the traffic patterns along Wilshire in order to accommodate those who wanted to pull off to one side of the street or the other, and spend some money on something that caught their eye.

Which is how we got dedicated left turn lanes—the first ever in the United States.

Such urban planning helped retailers like the May Company (department store) thrive, and its 1939 building designed by A.C. Martin—considered one of the best extant examples of Streamline Moderne still in Los Angeles—survive nearly eight decades.

Although the department store is long gone, the building still stands and will soon house the hotly debated and widely anticipated Academy Museum of Motion Pictures—another contribution to our modern-day Museum Row.

Likewise, this commercial district continued to serve motorists’ needs into the decade perhaps known best for its “car culture,” the 1960s—including with the construction of architect Welton Becket’s New Formalist contribution to Miracle Mile in 1962.

Initially, the structure housed Seibu Department Store, though it quickly flipped over to Ohrbach’s, which operated there through the ’60s and into the mid-’80s.

Becket’s design provided a glimpse into the precast concrete columns that would later adorn other LA landmarks, like the Music Center in Downtown LA.

But this building on Wilshire was the first.

In 1994, that frontage was modified upon the reopening of the building, now as the Petersen Automotive Museum—fittingly, a cultural institution devoted to cars and car culture, right there on the busy corner of Fairfax and Wilshire.

“Fins,” like those you’d find on a classic car or at a mid-century car wash, were added, and beckoned auto enthusiasts to come in and look at the enormous collection.

Now, of course, thanks to a $125-million renovation and a brand-new “ribbon”-style, red and silver façade that debuted in 2015, its yesteryear days as a clothing storefront are beyond recognition.

But as Wilshire Boulevard evolves, it becomes no less important or revolutionary—now boasting one of the world’s largest automobile museums right down the street from those old tar pits.

And if you want to go shopping? Well, just hop in your car or on your bike (or the Metro when the Purple Line Extension finally opens) and head west to Beverly Hills.

You can follow Wilshire the whole way there.

All Bullocks Wilshire photos by Sandi Hemmerlein