SoCal and Astronomical History: The Big Bang Theory, the Demise of Pluto & More

With L.A.'s night sky shrouded in a veil of smog and light pollution, Southern California might seem an unlikely place for star-gazing scientists to congregate. But before population growth and industrialization transformed the night sky into a dull glow, Southern California's generally cloudless climate attracted some of the world's finest astronomers.

The region's most prominent observatory, in Griffith Park, has always been more of an educational facility rather than an active center for scientific research. Perched above Los Angeles in the Hollywood Hills, the Griffith Observatory opened on May 14, 1935 and was originally envisioned by mining baron Griffith J. Griffith, who became interested in astronomy after peering through the telescope of an observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains.

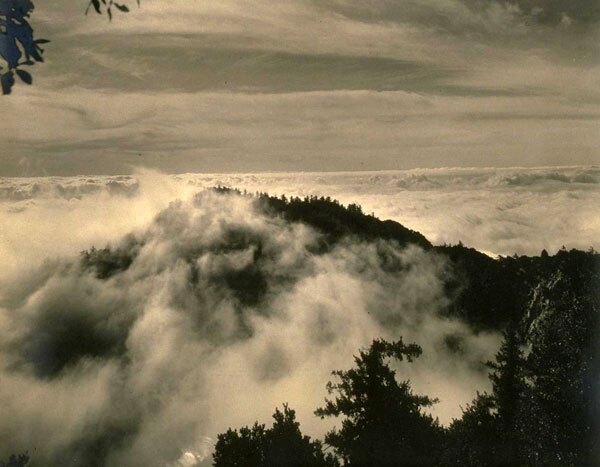

It was at that facility -- the Mount Wilson Observatory -- that many of Southern California's great astronomical discoveries were made. Plans for an observatory on the summit overlooking Pasadena dated to the 1880s, when businessman E. F. Spence, USC president Marion F. Bovard, and a team of Harvard scientists conducted the first observations from the peak with a 13-inch telescope. They were satisfied with their results; at 5,715 feet above sea level, Mount Wilson peeks through the inversion layer, leaving fog and airborne pollution below and calm, steady air above. Although the proposal gained wide approval among astronomers nationwide, financial troubles plagued the plan and forced USC and Harvard to shelve it in 1892.

It fell to George Ellery Hale, a solar astronomer who first heard about Mount Wilson as an MIT student, to bring Southern California its first scientific facility dedicated to stargazing. With backing from the Carnegie Institute, Hale founded the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1904. When it became operational in 1908, the observatory's 60-inch reflector telescope was the largest in the world. Nine years later, Hale added an even larger device, the 100-inch Hooker Telescope.

Boasting unparalleled powers of magnification, Mount Wilson added some of the world's finest astronomers to its roster of scientists. Hale himself was a noted scientist who helped transform what was then a vocational school named Throop University into the research university we know today as Caltech.

In 1917, Harlow Shapley used the 60-inch telescope to identify the center of the Milky Way, calculate the galaxy's size, and determine our solar system's location within it. In 1925, Edwin Hubble used observations from Mount Wilson to demonstrate that the Milky Way was merely one of many galaxies in the universe, and four years later Hubble found the first observational evidence for the Big Bang theory. The Hubble constant, which describes the relationship between how fast an object is receding from Earth and how distant it is from us, is one of the foundations of modern cosmology.

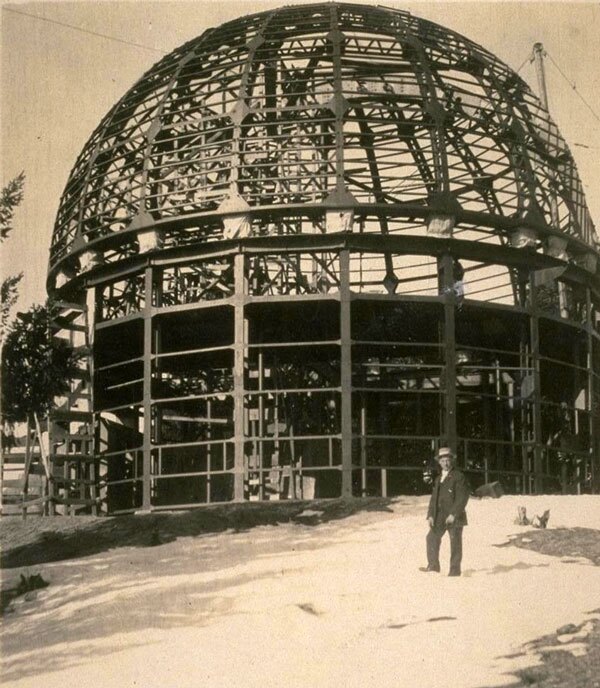

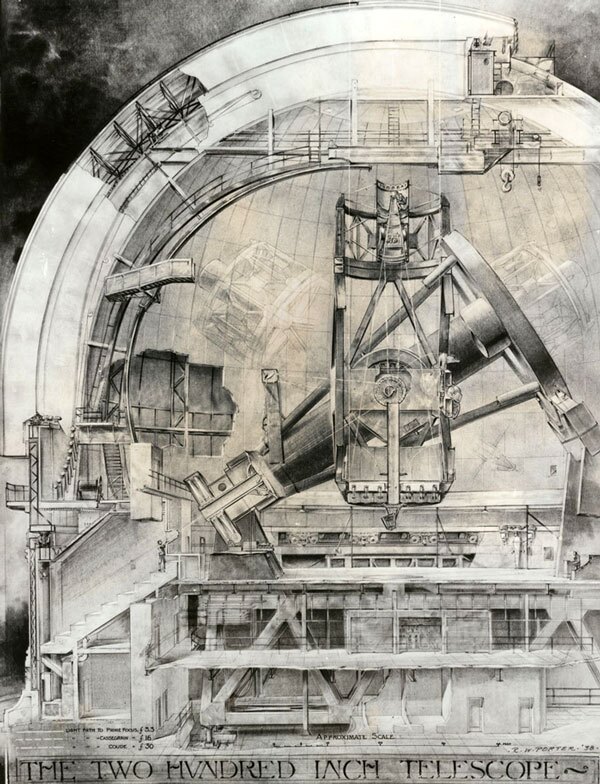

By the 1930s, light pollution from the growing metropolis of Los Angeles had compromised Mount Wilson's fitness for astronomy. Hale and Caltech searched for a replacement site and landed upon Palomar Mountain, 45 miles northeast of San Diego. Delayed by World War II, the new observatory took 15 years to build and cost millions of dollars. Hale would not live to see its completion, but when the Palomar Observatory opened in 1949 its 200-inch telescope, named in Hale's memory, displaced the Mount Wilson's Hooker Telescope as the world's largest. Hubble was the first to use the telescope.

With Palomar's opening, Southern California remained a leading center of astronomical research. In the 1960s, astronomers at Palomar discovered quasars--bright, distant galaxies that are among the oldest visible objects in the universe--and established methods for measuring extragalactic distances.

While the advent of space-based astronomy and the opening of an even-larger telescope on Hawaii's Mauna Kea have introduced new rivals to Palomar, the observatory remains at the center of groundbreaking scientific discovery -- much to the sorrow of fans of Pluto, a distant object once considered the Solar System's ninth planet. In 2005, Palomar's Hale telescope captured the first images of Eris, a dwarf planet 27 percent more massive than Pluto. Astronomers at first considered naming Eris the Solar System's tenth planet, but eventually chose instead to evict Pluto from the list of planets--a decision that drew howls of protest from admirers of the diminutive orb of ice and rock.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, personal collections, and other institutions. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and cultural institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.