Farewell To Manzanar? A Solar Future Threatens a Sensitive Past

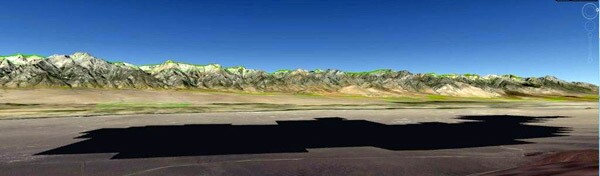

Drive up the 14 Freeway, past the Antelope Valley and Kern County, and onto U.S. 395, past the Owens Dry Lake bed and the town of Lone Pine, and you'll see it. Among the endless acres of alkaline desert brush, nestled in this deep valley sandwiched between two majestic, snowcapped mountain ranges, a guard tower appears, seemingly out of nowhere, and the brown-colored highway signs bear the name of the place.

Manzanar.

For this was the very place, some 70 years ago, where up to 10,046 Americans of Japanese ancestry -- many from the Los Angeles area -- were suddenly uprooted from their daily lives and forced to live in virtual imprisonment, without any formal charges nor due process of the law. It was one of 10 "War Relocation Centers" that stretched from California to Arkansas, designed to "protect" Japanese Americans, as the U.S. government claimed at the time. Yet, the guns at the guard houses pointed in, and not out, and while America was also at war with Germany and Italy, German- and Italian- Americans were not confined in the same manner. "Why us?" the Japanese American community wondered.

Today, following years of reparations, redress, and remembrance, Manzanar stands as a National Historic Site, run by the National Park Service, as a living history lesson and reminder of a regrettable time in our country's past, so that the same mistake will not be repeated again. A decade ago, the auditorium building was converted into an interpretive center, replete with historic items, displays, photographs, and multimedia presentations that relay the internment experience. In late April of each year, surviving internees, their families and other community members make an annual pilgrimage visit to Manzanar, which still sits silent on the floor of the Owens Valley, save for the occasional wind and cars passing on the highway. It is a constant reminder of Manzanar's intended solitude. A semblance of peace amidst memories during a time of war and occasional chaos.

That peace and solitude are now being threatened by a pair of industrial energy projects proposed to be built in close proximity to the National Historic Site. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power intends to build the Southern Owens Valley Solar Ranch, a 1,200-acre, 200 megawatt photovoltaic solar power facility across the highway from Manzanar. And another project, a similar-sized solar power facility planned to be built on private land some five miles to the northeast, by Canadian energy company Northland Power, is also feared to become a visual blight and distraction to the Manzanar experience. The LADWP contends that the elevation of the site and its proximity to long-distance power transmission lines (plus their ownership of the land, acquired a century ago for water rights pertaining to the nearby Los Angeles Aqueduct) make its Manzanar-adjacent location an "ideal site." The Northland Power project has similar reasons for their location.

"Why us?" the Japanese American community wonders once again.

"It's another eyesore in the name of profit," said Hank Umemoto, who was interned at Manzanar as a teenager. The 85 year-old Gardena resident likened the LADWP's Solar Ranch plan to the environmental destruction brought on to nearby Owens Lake, a body of water some 20 miles south of Manzanar that was desiccated due to the impact of the L.A. Aqueduct.

"[Manzanar's] Interpretive Center is there to tell the story so that it may never happen again. It is there to tell a story in an environment as it were, untouched by distracting structures as solar panels on a stage," said Umemoto.

His sentiments were echoed by Arnold Maeda, 87, of Mar Vista, who was also interned at Manzanar as a teen and summed up his experience there as, "a bad time for people my age to get cooped up behind barbed wire."

Maeda considered the proposed solar project to be a distraction. "It would destroy the pristine land. I understand there are many other places that the DWP can establish a solar plant, I don't want to see them [at Manzanar]. I'd like to see the people who visit to see [Manzanar] the way it was, without any disturbing things in the area," he said.

"I think it's really important for the story that is being told here to have that visual sense that the isolated, undeveloped nature of this area was so vital for the selection of the site of this camp," said Les Inafuku, former superintendent at Manzanar National Historic Site, who just last week retired from a 37-year career with the National Park Service. "Most of our visitors are urbanites. To have have an industrial site across the highway, would just make this area seem more like what they have down in L.A. or San Diego. The opportunity for visitors to learn here at Manzanar is greatly enhanced by maintaining the undeveloped nature of this greater area."

During my last visit to Manzanar in mid-December, Inafuku drove me to the LADWP's Solar Ranch site, some three miles due east. We crossed the abandoned World War II-era airfield that was intended to be an emergency air base in the event of a military retreat from the coast. We passed the L.A. Aqueduct and the Owens River, which was surrounded by ice. We saw frozen ponds and clumps of snow concealed in shadows, remnants of a recent storm. We even saw modern-day cowboys, rounding up cattle that grazes in the area. Unlike the city, where blocks, buildings and landmarks help establish the scale of distance, it's hard to visually discern three miles, or 1,200 acres with the eye here in the expanses of the Owens Valley, and yet, it's part of its allure.

Inafuku pulled over to the side of the dirt road and pointed out the area to the north of the road that was proposed to become LADWP's Solar Ranch project. Manzanar's interpretive center can be seen as a solitary building toward the west. He also pointed out that a 300,000-square foot substation building would be built as part of the project, which is comparatively larger than a massive Walmart Supercenter. I also pointed out the scale of the 1,200-acre project, which equals 1.87 square miles -- in comparison, the entire city of West Hollywood amounts to 1.88 square miles.

We went back to Manzanar and went up to the cemetery, near the northwestern corner of the site. Though most of the graves were eventually relocated, six bodies remain buried here. The cemetery, the focal point of the annual Manzanar pilgrimages, is regarded as the most sacred part of the site, marked by the "Soul consoling tower" obelisk landmark that stands here.

At a public hearing at the DWP's headquarters in mid-November, where a large number of Japanese Americans, including former Manzanar internees, gave public comments, the LADWP produced a photo rendering of the view of their Solar Ranch project from Manzanar, which maintained that only a thin, hardly-visible strip could be seen. But that view was taken from the vantage point of Manzanar's visitor parking lot, at 3,859 feet above sea level. The cemetery, located higher on the Sierra Nevada alluvial plain, is situated at 3,970 feet n elevation. What appears as a thin, hardly-visible strip isn't as inconspicuous from 111 feet higher up. The Northland Power solar plant, proposed to be situated further up on the Inyo Mountains' alluvial plain, would be even more apparent, despite being a few miles farther away.

Later, Inafuku took me to Manzanar's reservoir, an empty concrete basin that once supplied the water needs of the 10,000 people who lived there. At 4,099 feet in elevation, it is not currently part of the National Historic Site, but it is located on federal Bureau of Land Management property and could be included into an expanded National Historic Site at a future date. From there, the locations of both solar projects were easily seen.

"I've heard from many visitors to Manzanar who said that they never knew about it until they were driving down the highway and saw guard tower...It caught their eye enough that they stopped and went in," said L.A. resident Bruce Embrey, co-chair of the Manzanar Committee. "To say that the line of sight for the immediate area isn't significant to the Manzanar experience, and dismiss it, belies our own experience."

Embrey's organization stages the annual Manzanar pilgrimage and promotes the social justice aspect of the Japanese American internment experience. They have recently launched an online petition drive, calling for stopping the Solar Ranch.

Embrey's involvement with Manzanar has been a lifelong endeavor -- his late mother, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, was interned there as a young adult, along with her mother and siblings. Later in life, she became a leader within L.A.'s Japanese American community and served as a commissioner under Mayor Tom Bradley's administration. She was instrumental in getting the support of then-U.S. Congressman Mel Levine, who co-sponsored legislation in 1992 to designate Manzanar as a National Historic Site.

Today, Levine serves as the new president of LADWP's Board of Commissioners.

Embrey, along with fellow members of his organization, former Manzanar internees and concerned Japanese Americans, spoke out at November's public hearing in a crowded LADWP conference room on their opposition to the Solar Ranch project. They were joined by native Paiute-Shoshone tribal members, environmentalists, writers, academics, and visiting Owens Valley residents (who have a century-long contentious history with the LADWP), all voicing their own distaste for the Solar Ranch.

Manzanar has its own history with the LADWP. Originally an agricultural town, named so in Spanish for the apple orchards that once flourished there, it became a ghost town after the LADWP started pumping groundwater into the L.A. Aqueduct in the 1920s. In 1933, they purchased the land for water rights, and leased 6,200 acres of it to the U.S. Army in 1942 for the War Relocation Center.

"The DWP opposed the establishment of the National Historic Site, up until a few weeks before final legislation passed," said Embrey. His mother, a staunch supporter of Bradley, helped convince the mayor to get the LADWP to eventually support the site. L.A. City Council proclamation certificates hang in the halls of the interpretive center today.

Opponents of the project are quick to point out that they are not against solar energy per se. The interpretive center at Manzanar is itself powered by renewable energy, in the form of low-profile solar panels atop a non-historic, reconstructed wing of the building. I didn't even notice them until Inafuku pointed them out to me. The panels were built in 2010 through American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus funds, and they currently provide 20 percent of Manzanar's electrical power needs.

"I don't believe that large, industrial solar is a wise use of resources," said Embrey, who by trade works as a general contractor who specializes in commercial and residential energy efficiency projects, which include solar panels. "The cost to build the infrastructure for distributed transmission undercuts the purpose."

Embrey contended that the LADWP, through their net metering, pays 17 cents to L.A. residents per kilowatt hour, as compared to 14 cents to Owens Valley residents, since it costs the LADWP more to bring the electricity down to the city -- a difference of 20 percent. He would like to see the widespread use of rooftop solar generation here in Los Angeles as an alternative, as a recent UCLA mapping study suggests.

"We've barely begun to dent the solar generating capacity here in L.A.," Embrey said. "There's tons of unused solar energy capacity here in the city."

Back at Manzanar during my visit last month, I came to the realization that although it is a historic site, it is not a static location. Inafuku pointed out a concrete koi pond and garden site that was recently excavated in Block 33, thanks to a former internee's recollections as a young girl. Despite what some may think, the Manzanar site is not exactly untouched as it was left seven decades ago. The staff and crew have to battle the forces of nature, in the form of floods and wind, to preserve and excavate areas that were once regarded as mounds of dirt in the ground, in order to tell the Manzanar story. Would they have to eventually wrestle with a man-made force, one that could have been entirely avoidable?

I also recalled my first visit to the place, just over a year ago, realizing that the bitter cold of winter (and the searing heat of summer), coupled with the apparent remoteness of the location, were like forms of passive torture for the internees. Would a future Manzanar visitor receive the same perspective with one or two large, modern distractions looming in the distance? Something would definitely be lost forever in that case. Is it all worth bidding a regrettable farewell to Manzanar as we know it?