Drive-in Megachurch to Catholic Cathedral: Sacred Spaces in Transition

I went over to Garden Grove because something odd is happening there, suspended in sacred time between the Rev. Robert H. Schuller's megachurch and what intends to be Christ Cathedral of the Catholic Diocese of Orange. The transition from one to the other is both fascinating and puzzling.

The former campus of Schuller's ministry is a complex of buildings, four of them by some of the 20th century's great architects -- Richard Neutra, Philip Johnson, and Richard Meier -- and a fifth by the lesser-known Gin Wong.

The buildings are surrounded by 34 acres of parking lots, landscaping going a little weedy from inattention, and massive sculptures of a beefy Jesus and a pissed-off Moses. There's a cemetery, too.

Schuller's bankruptcy sale of the Crystal Cathedral for $57.5 million was a bargain for the Diocese of Orange, but the custodianship of all this architecture also is something of a burden. The diocese is in the opening stages of at least $53 million in renovation and restoration.

Partly, this has gone remarkably well. Richard Neutra's original Garden Grove Community Church -- the media-smart Schuller's starting place in the 1950s -- has been refreshed, air conditioned, and given a garden (nearly finished) that's in keeping with Neutra's original 1961 plan.

The adjacent buildings -- low, simple, embracing of light and air in the Neutra manner -- have also been lightly touched.

The church building (1961) is locally famous for its "drive-in" features: a wide balcony that once overlooked a former drive-in movie theater's parking lot into which an amplified Schuller would preach on Sundays, the parked cars listening on the theater's speakers. In 1970, Schuller began broadcasting his upbeat messages to television audiences.

A 12-story tower by Neutra and his son Dion (1968) crowds one end of the complex. The tower was once the tallest structure in Orange County. It awaits earthquake retrofitting. Although not well regarded by contemporary critics -- too backward looking for the late 1960s -- the tower's harmonious verticals and cast concrete stairs are vigorous enough.

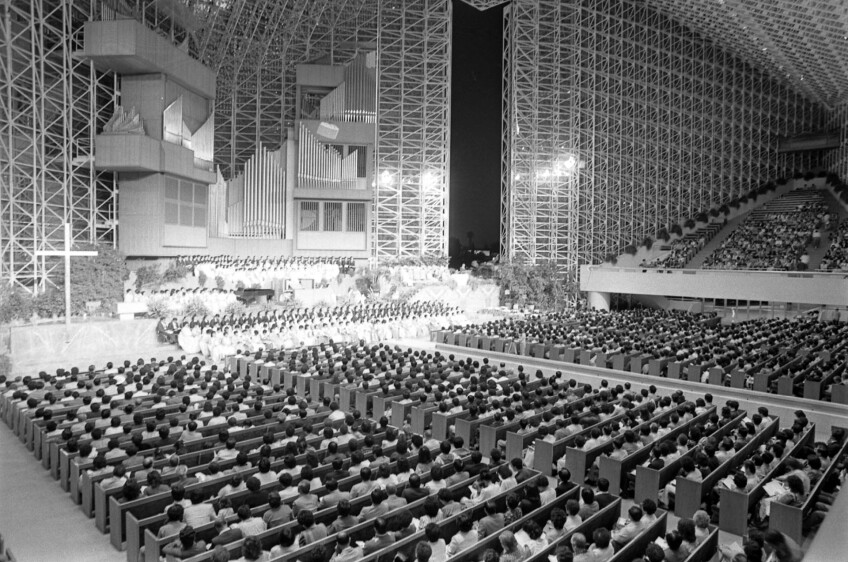

Philip Johnson's glazed and spider-webby Chrystal Cathedral (1980) is the primary focus of the diocese's re-churching. The friendly docent who chatted with me seemed a little dazed at what it will require to take this idiosyncratic lecture hall -- facing a massive stone stage and a pipe organ -- and turn it into a Catholic church. There isn't even room to kneel between the rows of theater-style seats.

Adjacent to the cathedral is a Richard Meier office building, theater, and classroom structure (2003) clad in stainless steel panels apparently beginning to rust at the joints.

When I was there, workmen were inside the nearby Gin Wong's office complex (1990), readying it as an elementary school and diocesan offices. Meier's building was empty, and I walked through the carpeted rooms with their blank, white walls. Some debris of the Schuller period remained on the third flood -- exhortations from Schuller's gospel of "possibility thinking," a model of the ministry's campus,and a chapel devoted to dreams.

A few former dreams were posted on one wall.

Catholic churches -- in Southern California, at least -- are relatively muted on the subject of personal recognition. You go to mass on Sunday, throw your envelope in the collection basket, and get on mending your broken life.

The gospel according to Schuller apparently needed a larger affirmation that good had been done. Just about every flat surface -- walls, glass screens, and paved walkways -- was destined to commemorate someone's substantial contribution to Schuller's version of positive thinking.

There must be thousands of names. Some engraved paving stones, like so many grave markers, are being taken away by the original donors now that the cathedral's message is Catholic and not middle-class uplift.

I wonder if any of the Crystal Cathedral's dead -- which includes Marie Callender of pie fame -- will take a powder, too.