It Ties the Ocean to the Mountains: A History of Salmon in California

The unthinkable happened in 2008: California ran out of salmon. Drought had starved the state’s rivers, already seriously depleted by diversions of water for California’s farms and cities. The fall run of Sacramento River chinook salmon was once a wildlife wonder to rival the herds of the Serengeti and the Great Barrier Reef. In 2008, it collapsed. The Sacramento’s water was too warm, too choked with algae and salt, and too non-existent to allow the fall-run Chinook to survive their trip from their birth waters down to the Pacific Ocean. Federal officials closed the California chinook ocean fishery.

They kept the fishery closed for another year after that.

It wasn’t just chinook in the Sacramento River. By January 2009, so few coho salmon had returned to the Lagunitas Creek watershed in Marin County, north of San Francisco, that one fisheries biologist told the San Francisco Chronicle “the fish are missing. They are gone.”

It was an overstatement, but only a small one. The spawning coho’s numbers had merely dropped by 89 percent since they left the watershed as new adults three years earlier. Lagunitas Creek, whose tributaries run mainly through protected land, had been considered a poster child for the possible survival of coho salmon on the California coast. Fans of coho salmon in other watersheds had looked to the Lagunitas Creek run for inspiration. In late 2008, that inspiration turned to despair.

Salmon throughout California were in trouble that year, but the collapse of the state’s healthiest runs of both coho and chinook commanded special attention. For a while. The salmon's plight has intensified since then, as has the state's drought. But public attention has shifted away from the chinook and the coho.

It is hard to overstate the magnitude of the collapse of California’s salmon runs in the two centuries between 1809 and 2009. Mentions of California salmon runs by the first American settlers were often taken as hyperbole of the kind usually employed by mine promoters and real estate speculators. There were stories of walking across the Feather River using spawning chinook as stepping stones. Some wrote of harvesting a years’ supply of meat in a few hours by standing in a stream with a pitchfork and shoveling salmon onto the bank.

A useful and somewhat more restrained description comes from a contemporary writer who himself had a reputation for stretching the truth until it was so thin you could read newsprint through it. In 1873, in his book “Life Amongst the Modocs,” the poet Joaquin Miller wrote one of the first elegies to California’s disappearing salmon:

These fish in the springtime pour up these streams from the sea in incalculable schools. They fairly darken the water. On the head of the Sacramento, before that once beautiful river was changed from a silver sheet to a dirty yellow stream, I have seen between the Devil's Castle [Castle Crags] and Mount Shasta the stream so filled with salmon that it was impossible to force a horse across the current. Of course this was not usual, and now can only be met with hard up at the heads of mountain streams, where mining is not carried on and where the advance of the fish is checked by falls on the head of the stream. The amount of salmon which the Indians would spear and dry in the sun and hoard away for winter under such circumstances can be imagined.

There are five species of salmon found naturally in California rivers and streams, or six, depending on how you define “salmon.” Of these, only two species (or three, depending) occurred in large enough numbers before the settlement of California to have been significant to either the state’s ecological cycles or Native culture.

Those two salmon species are the chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, the largest of all the Pacific salmon, and the smaller coho, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Every swimmable stream of any size connected to the Pacific from Santa Cruz on north had runs of either coho or chinook, or both, prior to the advent of industrial society. Coastal streams from the Oregon line as far south as Baja California held that problematic “depending on how you define salmon” salmon species, the steelhead. If the steelhead had two feet, one of them would be planted in the “salmon” category and the other in “trout.” It’s the same species, Oncorhynchus mykiss, as the rainbow trout. Scientists have found no genetic distinction between steelhead and rainbow trout sufficient to explain the radical difference in their lifestyles. That difference? Rainbow trout stay in fresh water their whole lives, while steelhead head downstream into the ocean, grow large, then return to their natal creeks to spawn. Unlike chinooks and coho, steelhead survive spawning fairly often. After spawning, those lucky steelhead swim back out to sea for another circuit on the reproductive merry go round.

That leaves three other species of salmon: the pink, chum, and sockeye. It’s probably stretching the definition of “native” to refer to sockeye salmon as native to California: they usually don’t venture south of the Columbia River to spawn. A few have wandered into the Klamath River from time to time, and humans have deliberately planted sockeyes in Tahoe and other California lakes, from which a few sometimes escape. Planted, landlocked sockeye salmon are called “kokanee” by anglers.

Pink and chum salmon are truly native to California: they’re just not abundant. Even before the state’s salmon runs collapsed, just a few pink or chum salmon could be found in the state’s major rivers during spawning time.

The salmon life cycle is basically the same regardless of species. Adults ready to spawn hold offshore until rivers or streams swell, bringing more fresh water into the estuary. When the creeks are high enough, the fish head inland. Coho tend to like steep coastal streams like Lagunitas Creek for spawning, while chinook usually opt for big main-stem rivers like the Sacramento or the Klamath. That makes sense: chinook can reach lengths in excess of three feet and weigh about 30 pounds: there just isn’t room in coastal creeks for them to swim. Coho, averaging two feet long and averaging a svelte eight or ten pounds, are like sports cars compared to the 18-wheeler chinook. Coho can handle coastal creeks just fine.

Spawning salmon home in on the tributary where they hatched by scent. It’s as if you were taken from your birthplace at age two, and then had to return as an adult using only the remembered scents of the freeways to find your way home.

Once in the river or creek and heading upstream, the fish literally home in on the tributary where they hatched. It’s generally accepted that they do so by scent, distinguishing the flavor of their home creek even mixed into the outflow of perhaps three or four dozen other streams. It’s as if you were taken from your birthplace at age one or two, and then asked in adulthood to return using only the remembered scents of the freeways on the way home.

When the adults find a stretch of creek that seems suitable, spawning begins — and so does the fisheries biologist jargon. With strokes of their strong tails, the females scoop out nests in the creekbed gravel: “redds.” They lay eggs in the gravel. Males release a cloud of sperm — “milt” — onto the eggs, fertilizing them. Buried as deep as a foot and a half below the creek bed, kept alive by the constant flow of oxygenated water through the gravel, the eggs hatch out into “alevin” —tiny baby fish with their yolk sacs still attached. The alevin stay buried in the gravel until the food in their yolk sacs is used up. When that happens, they emerge as tiny “fry” and start finding their own nearly microscopic food in the creek’s cold water.

In other parts of their range, chinook and coho fry can stay in their birth creeks for several years. In California, where the creeks sometimes get too dry in summer to keep fry alive, the growing salmon “smolts” start letting their creeks carry them down to the sea within a year of hatching. They feed along the way in submerged wetlands and shallow estuaries. Eventually, as young adults, they head out into the salt water to feed in the open ocean, growing to prodigious lengths before returning to freshwater — usually for three years but sometimes returning as “jacks” and “jills” in just two years — to spawn and complete the cycle.

Salmon are thus a link between ecosystems that couldn’t seem more different: the open ocean on one hand and interior mountains on the other. In the days when massive numbers of salmon regularly spent themselves battling their way up California’s rivers as far as the rivers would allow, salmon runs became a massive subsidy of mountain river ecosystems, as if the nutrients that had washed out to sea in spring floods washed themselves right back up again with the chinook and coho.

Not only did spawned-out adults contribute fertilizer to streamside plants as they succumbed, but just about any Californian animal capable of eating flesh would take advantage of the mass of protein heading upstream. Black bears and grizzlies, wolves and coyotes, river otters and martens and fishers and ringtails, bobcats and pumas and bald eagles and ospreys and other animals too numerous to recount would haul their share of the salmon’s bounty away from the river, there to add it to the local landscape’s nutrient cycles.

At the other end of their life cycle, salmon fed animals from fish to sea lions to orcas. The need to return to the ocean completes the cycle of connection. Like almost every other flow in the natural world, the flow of salmon goes both ways. Salmon need healthy, abundant river flows to spawn. They also need healthy river flows to survive hatching and get to the ocean. A starved, slack river is too warm for the smolts to survive. A sediment-laden river will suffocate eggs and alevin in their gravel beds.

In 2008, we merely saw the inevitable result of two centuries of mistreatment of California’s rivers. And all that time, there were Californians who knew a better way.

California Indian peoples’ relationships with the salmon with whom they shared the landscape were, and are, diverse. For some people, salmon and steelhead were historically a minor but cherished part of their diet. For others, especially those peoples living along the north state’s rivers, salmon were the staff of life. Salmon and tan oak acorns, for instance, made up more than half of the traditional diet of the Karuk people along the Klamath River, and much the same was true of the Karuk’s neighbors. The importance of salmon to the diet of the Klamath River tribes ensured the centrality of salmon in those tribes’ cultures. That centrality continues today even as the people’s continuing access to salmon comes ever more in doubt.

Cattle grazing during the Mission era likely caused some damage to coastal steelhead runs, as livestock hooves stirred up streambed sediment, which may well have been increased in grazed areas. But damage to the state’s salmon runs began in earnest with the advent of American settlers. Here’s Joaquin Miller, again, in Life Amongst the Modocs, describing the first effects of American industry on a salmon run that remains among the state’s most important, and subsequently on the people that depended on those salmon:

Another thing that made it rather more hard on the Indians than anything else, was the utter failure of the annual run of salmon the summer before on account of the muddy water. The Klamat, which had poured from the mountain lakes to the sea as clear as glass, was now made muddy and turbid from the miners washing for gold on its banks and its tributaries. The trout turned on their sides and died; the salmon from the sea came in but rarely on account of this; and what few did come were pretty safe from the spears of the Indians because of the coloured water; so that supply which was more than all others their bread and their meat was entirely cut off.

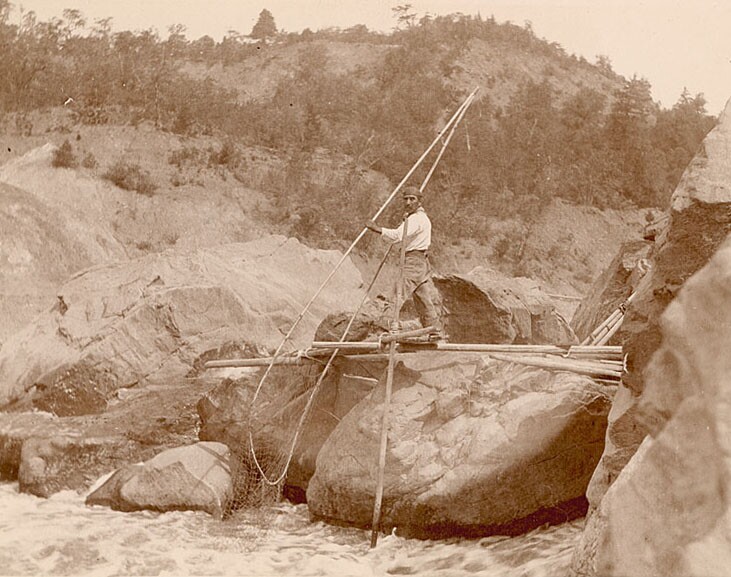

There was a bitter irony to the misery caused by miners’ beginning destruction of the Klamath salmon: the tribes along the Klamath had for millennia lived off the salmon, harvesting prodigious amounts of fish, without doing apparent harm to the fishery or depriving neighboring tribes of sustenance. That’s despite the fact that the Karuk and their neighbors were completely capable, in the technological sense, of overharvesting Klamath chinook and coho.

In 2014, sociologist Kari Norgaard wrote a report for the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural resources entitled “Karuk Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Need for Knowledge Sovereignty,”which examined the effects on Native culture and health, as well as on the environment in the Klamath watershed, of the last two centuries of wresting land management from the hands of Native people. Norgaard’s description of the Karuk people’s traditional relationship with the Klamath River’s salmon runs illustrates just how Klamath tribes were able to subsist on salmon without depleting the resource:

Under tribal management weirs were built by Karuk at Red Cap Creek and by Yurok further down the Klamath River below Pecwan, but no one began harvesting fish until a priest and his assistants performed a 10-day ceremony to catch the first salmon of the year at Ameekyáaraam. According to Karuk Ceremonial Leader and Director of the Department of Natural Resources Leaf Hillman, “Because the first fish [was] caught at Ameekyáaraam, they say the ‘fish medicine’ was made there.” After the first fish was caught, it was not consumed, but was ceremoniously offered on an altar. Only after this ceremony was completed were the Tribes along the mid and lower Klamath River permitted to fish.

That forbearance in not harvesting the first ten days of salmon went a long way toward ensuring the salmon would return year after year. Perhaps counterintuitively for Western minds, letting that first flush of fish go didn’t mean food scarcity. As Norgaard notes, “on the Klamath through coordinated ceremonial regulation and custom, tribal fishery management for centuries sustained an annual harvest of salmon equal to the peak of the harvest achieved by white settlers in only one year.”

That tribal management knowledge still exists. After 150 years of catastrophic drops in salmon numbers across California, the tribes along the Klamath — and along much of the thousands of miles of former salmon and steelhead habitat elsewhere in California — stand ready to bring back the fish.

I’ll go into more detail about ongoing threats to the salmon, and ways those threats might be addressed through Traditional Ecological Knowledge, in an upcoming article.

Banner image: juvenile chinook salmon. Photo: Roger Tabor / USFWS

Co-produced by KCETLink and the Autry Museum of the American West, the Tending the Wild series is presented in association with the Autry's groundbreaking California Continued exhibition.