When Embroidery Stitches a Portrait of Our Times

When Jan Miyabara was watching Amanda Gorman recite her poem, "The Hill We Climb," at this year's presidential inauguration, the national youth poet laureate's words struck a chord with her.

One line in particular stood out: "If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy…" Miyabara, a 38-year-old freelance fashion designer, began hand-stitching the words onto a cloth-covered hoop.

"[Those words] really resonated with me, so I wanted to commemorate it," Miyabara said.

She posted a photo of her finished product onto the Instagram page of her own company Aki & Co., and a couple of people reached out asking if she would sell it. Miyabara didn't feel comfortable making a profit off Gorman's words, so she offered to send it to a friend for free and did a swap with another who also owns a small business.

Miyabara is one of the number of Los Angeles-based artists — a mix of professionals and hobbyists — who have been using the craft of embroidery as a platform to express what has transpired over the past year. Their stitched words and pictures depicting the pandemic, Black Lives Matter movement, and other social issues have become a way to protest and record history.

In front of Naama Haviv's Highland Park home is a three-shelf glass display case that she's fashioned into a museum and roadside attraction. Aptly named "The Tiny," the case has been home to her self-initiated exhibits since last July.

Haviv's first exhibit centered on the theme of white fragility, a topic she explored shortly after the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man who police murdered in Minneapolis last May.

"I was talking with a lot of my friends, many of whom are white women like me, about our moments of — a little vocal reckoning of — all of the times that we had privilege and [chose] our own comfort over doing the right thing," Haviv, 42, said. "You know, when we said shitty things and even knew in the moment that it was shitty, but we were too embarrassed to even say sorry."

Haviv had her friends share those moments and write down key phrases from their stories. In their handwriting, she transferred the words to fabric and embroidered the letters and her designs onto three-inch hoops.

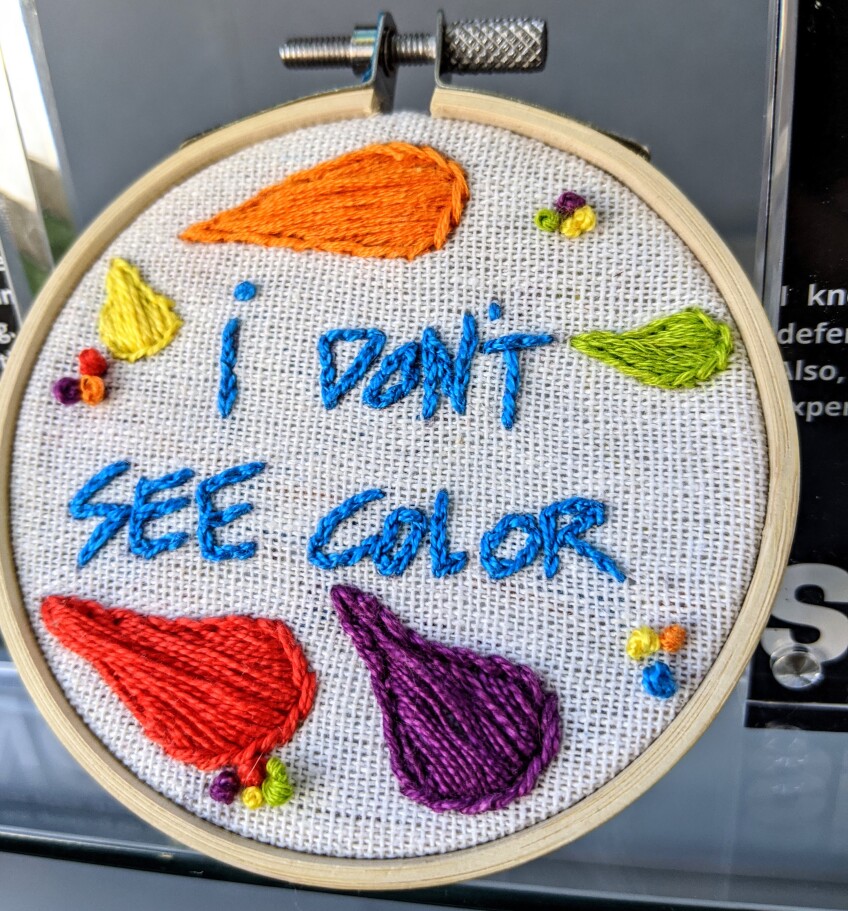

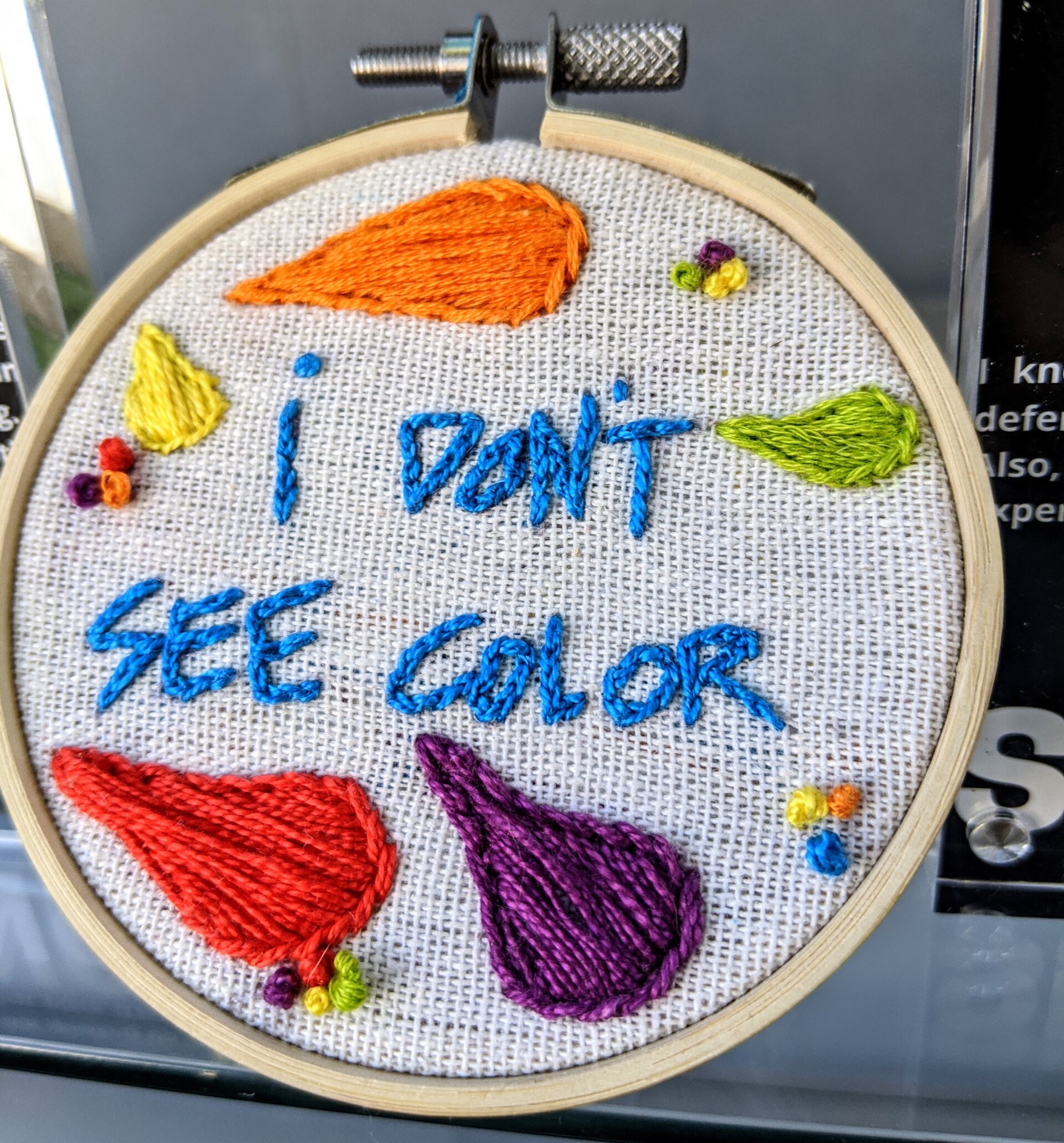

One of the pieces is dressed with the phrase "I said nothing," about a time when a friend of Haviv's froze and didn't say anything when a racial slur was used in front of her Black friend. Another hoop was woven with the words "I don't see color," a nod to a sentence another friend used to utter.

Haviv, who's the director of community engagement at MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger, doesn't consider herself an artist but rather someone who is good at crafts. She doesn't think of "The Tiny" as an art museum either. As someone with a B.A. in history and M.A. in Holocaust and genocide studies, Haviv said she thinks of herself more as a historian and her small museum as "a representation of the historical moments that we're in."

The chain stitch and chenille embroidery work that Jeff Kubasak, 37, does has been a historical account in many ways of the social issues that have been gaining attention over the past year. Kubasak, who embroiders using a 1930s Singer machine, is a freelance artist that does projects — both commissioned and self-initiated — under his company banner Common Genus.

A self-taught artist who works in many mediums, including photography, graphic design and woodworking, Kubasak has found sewing and embroidery to be a vehicle for activism. Amid the pandemic, he began using a sewing machine for the first time (he only had experience with embroidery machines until this point) to construct face masks. He sold the masks and used the profits to make more to donate to hospitals and homeless shelters in his East Hollywood neighborhood. Kubasak promoted and sold his masks using Instagram.

Around the time Floyd was murdered, Kubasak used the same mentality to reach out to others through social media about the anti-racism and BLM patches he was embroidering. Within five days, he made 200 patches and raised $1,400, which he donated to several organizations like the BLM Global Network Foundation, NAACP and Atlanta Solidarity Fund. People could donate anywhere from one cent to $20 for the patches.

"In fact, one person ordered 60 [patches] and paid 60 cents for them," Kubasak said. "[The person] had sent me an email saying, 'Hey, I want to spread these out and give them to a bunch of people,' so I was all for that."

Miyabara's work has related to the BLM movement, too. She's been stitching custom-ordered messages on masks during the pandemic, and one that she especially loved was the phrase "believe Black women."

In a collaboration Miyabara did with apparel brand People of Leisure, she created designs relating to the BLM movement. On the collar of one sweater, she embroidered the phrase "let it shine" — a line from the song "This Little Light of Mine" — as an homage to the Civil Rights movement anthem.

In another design, she adorned a sweater with the ouroboros symbol of a serpent eating its own tail. "[With] everything that was happening with BLM, I felt people were finally waking up to the injustices of what's been going on," Miyabara explained. "I felt like it was kind of the beginning of [a] new era of starting over."

Doing embroidery has been a nice departure from the redundancy of fast fashion for Miyabara. As exciting as fashion designing may sound to many, a lot of it is done on the computer, she explained. "[Embroidery] allowed me to slow down, create something with purpose and [make] something that's thoughtful."

When Miyabara is working on one of her embroidery projects, she tries to put intention into her stitching and transfer her energy through that. "I feel like there's kind of a responsibility passed on to me [when someone asks me to put a] phrase or something that's meaningful to them onto their T-shirt or jacket," she said. "So, I definitely feel like I need to do my best to see their vision come to light."

Kubasak, whose work is heavily inspired by skateboarding culture, said there's a message behind his designs: "I feel people need to either laugh a little bit more, give a shit a little bit more, or try a little harder."

On a large patch that he did in collaboration with artist Brian Smith, they have the word "Crisis" embellished across a map of the United States. Smith had drawn this design when the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting took place in 2012. They decided to bring it back as a patch last year.

"I definitely felt like this nation was in a very big crisis — and it still is in many ways," Kubasak said. "But I think leading up to the election, there was more than a palpable amount of stress and anxiety about what even the next few days could hold in the nation."

Recently, skateboarding shoe brand DC Shoes reached out to dozens of artists to design sneakers that would be auctioned to support Art Works for Change, a nonprofit organization that uses art to push forward social and environmental messages. Kubasak created a chenille pattern that featured the LGBTQ rainbow flag around the outer fabric, and the words "empathy calling" on the inner soles.

"[It's] the idea of being open and telling people that you've screwed up in your life and no one's perfect; we're all figuring it out," Kubasak said. "And [it's sending the message to try] to give a shit about other people. This is something that we need to start pushing out there."