Leslie Ito: Shiso and the Resilience of Arts

In Los Angeles County, over the last five years and more so in the last four months, I have seen many multi-issue foundations shifting their focus away from the arts and towards healthcare, food security and housing. I have been a part of many formal and informal conversations, and even internal personal debates, about the idea of what is essential in the wake of a pandemic and a growing social movement. This conversation made me reflect on my own family’s experience in the World War II concentration camps. When Japanese Americans were unjustly imprisoned, not only did they lose their freedom and all that comes along with liberty, they were forced to abandon culture, language and artistic practices for fear of being seen as the enemy. With the mandate of only being able to bring to the concentration camp what they could fit in a large duffle bag, my family undoubtedly were forced to think about what was essential.

As we have seen with the flourishing of the arts during the COVID-19 pandemic, from DJs popping up on Instagram Live to the soaring numbers of book sales and murals on boarded up windows with poignant, powerful messages calling for justice and in support of Black lives, the arts are flourishing. Some people believe that we take the arts for granted and that we will only see the true value of the arts when they are stripped away. In my experience, the arts will never be erased. Unlike food and shelter, they cannot be taken away, they are within all of us. Art does not solely rely on the capitalist system.

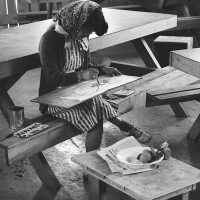

In the Japanese American concentration camps, artists found a way. My great grandfather, Ryosuke Funakoshi, along with others, carved beautiful sculptures from materials collected in the barren desert surroundings. Toyo Miyatake, renowned photographer, smuggled camera parts into Manzanar camp to build a camera and continue his photography. Desolate land was cultivated into beautiful gardens to continue centuries old Japanese traditions of horticulture. Ironically, while this may have appeared un-American and counter to the very reason why 120,000 innocent Japanese Americans were imprisoned, the American government recognized the power of arts and cultural activities to keep the peace inside the prison, and for the inmates, arts and culture gave focus and purpose and provided a sense of hope and connection.

The arts are beyond essential. If creativity resides in all of us, then why do we need to nurture it? Why invest in it, if it will flourish on its own? It will regenerate even in the most challenging of situations and yet, imagine if we actually nurtured it during the good times, in preparation to keep ourselves whole during the challenging ones. It reminds me of the bright green shiso (Japanese herb related to the mint) plant that I bought last summer at the Obon, an annual Japanese festival commemorating our ancestors. I have yet to master how to take care of this plant, and yet despite my overzealous watering followed by neglect and the intense San Gabriel Valley sun that eventually crisped it to a brown skeleton, somehow it persevered. This spring, in the midst of the start of our pandemic, I began to see tiny sprouts in the neighboring pots. Now, this time, I have the time and foresight to care for these plants, plenty just enough water, indirect sunlight and plenty of space and I will grow a field of shiso to be shared with loved ones in salads, as a garnish for fried rice and an added herbaceous kick to a piece of sashimi.

Just like the air we breathe and the shiso I grow in my container garden, the arts will never go away and yet this doesn’t mean we should stop nurturing them. The arts will flourish in the most hostile of environments — and yet imagine if we provide the necessary resources for diverse artists to flourish and for arts organizations and culturally equitable systems to support them.

Top Image: Adult art classes learning freehand brush strokes. | Dorothea Lange, War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement / National Archives