In this Pasadena Church, God and Thought-Provoking Art Share Space

For about a year now, artist Gregory Michael Hernandez has been putting together thought-provoking exhibitions as the artist-in-residence at an unlikely institution: the Missiongathering Christian Church of Pasadena. Called Irenic Projects, this arrangement came about casually and organically, but not randomly; one could argue it’s the logical culmination of Hernandez’s unique life journey.

Irenic Means Peaceful or Conciliatory

The artist has been a resident of the neighborhood around the church for several years, and his children attended preschool on its grounds. The church itself had been inactive for a couple years, following the dissolution of the Pasadena Christian Church. Then, in the weeks leading up to Easter in 2019, a new pastor came to town to establish a fresh congregation under the aegis of the Disciples of Christ, who are the longtime owners of the property. Pastor Rich McCullen was young and identified as gay, and the new Missiongathering congregation would be a progressive and inclusive one.

Hernandez became friendly with the pastor, who expressed anxiety about how he would decorate the church in time for a festive Easter opening. In response, the artist offered to quickly install an interactive outdoor sculpture that he had completed and exhibited in 2017. Called “Decalogue Chapel: The Ten Commandments Re-Contextualized,” the piece essentially reframes the Ten Commandments within a contemporary social justice context. McCullen loved it, and so did the crowd of 50 congregants who came to the opening.

In another conversation, McCullen revealed that he was at a loss as to what to do with the church’s side chapel. Hernandez saw an opportunity: he offered to become the church’s artist-in-residence, organizing and installing six to eight shows per year, in exchange for use of the side chapel as his studio. The shows would explore the intersection between religion and politics, and their goal would be to inspire dialogue among local artists and parishioners. Since the two men were philosophically aligned — both favored diverse, thoughtful and even critical perspectives on religion over purely devotional artworks — the deal was quickly sealed, and Irenic Projects was born.

From Christian Artist to Honest Thomas

Hernandez, known to his friends as Mike, grew up in a Southern Baptist family in Southern California. Baptized at age eight, he was a fervent believer and obediently followed the teachings of the church. He never drank, waited until marriage to have sex and always told his parents what he was up to, earning the moniker “Christian Mikey” in high school. He went to Biola University with plans to become a minister and a devotional artist, spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ. He married a classmate at the end of junior year and they had a child together. But then came senior year.

An influential professor, Scott D. Young, began feeding the young artist “more advanced knowledge” — materials that were more philosophical and questioning of religion. Hernandez took to it with great interest and began to look more critically at his own faith, eventually seeing the inherent unfairness of certain Christian doctrines. This kicked off a long and difficult period of reckoning for him. After graduation, he made a conscious effort to experience more of the world and meet more different types of people. As he did so, his faith steadily fell away, his marriage ended in divorce, and he went through periods of not speaking to his family. He was on his own, undergoing a complete transformation of his belief systems.

Twenty years and a lot of living later, Hernandez has emerged as what he calls a “Christian atheist.” He no longer believes in the “supernatural” elements of Christianity, such as the existence of an all-knowing God, but he does still cherish Christian values, such as compassion, humility and social justice. With his new wife and their two young kids, he attends a progressive Episcopalian church, primarily for the sense of community and healing it brings.

Hernandez also maintains a healthy interest in contemporary theology. Earlier this year, he even gave a guest sermon for Missiongathering in which he laid out his position. He titled it “Honest Thomas,” a more flattering moniker for the traditional “Doubting Thomas,” because of his theory that Thomas, in daring to doubt Jesus’ resurrection, was in effect “the first atheist.”

“The Biblical Imagination”

At the beginning of November, tired of months of inactivity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Hernandez opened Irenic Projects’ first group show, “The Biblical Imagination.” Filled with imagery inspired by the Bible in one way or another, the show is installed throughout the foyer and sacred space of the church, creating a contemplative viewing experience not unlike the Stations of the Cross. The works, which present a fractured variety of perspectives on religion, faith and biblical lore, glimmer in the space like the church’s own stained glass windows.

Ben White is the artist whose background is most similar to Hernandez’s; he was a gung-ho evangelical until a college study-abroad stint opened his mind to other ways of thinking. His colorful, off-kilter paintings bring together biblical scenes, historical references and pop culture elements in a dreamlike, free-for-all visual collision. Edgar Arceneaux and Kim Dingle also hail from religious families and both are highly critical of the dogma. Dingle contributes an actual family relic to the exhibition — ancestor Cram Dingle’s comical alleged sighting of the Christ in a photograph of snow — while Arceneaux’s film, “A Time to Break Silence” (2014), dramatically displayed in the sacred space, blends the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the dystopian film “2001: A Space Odyssey” in a rumination on the future of American cities.

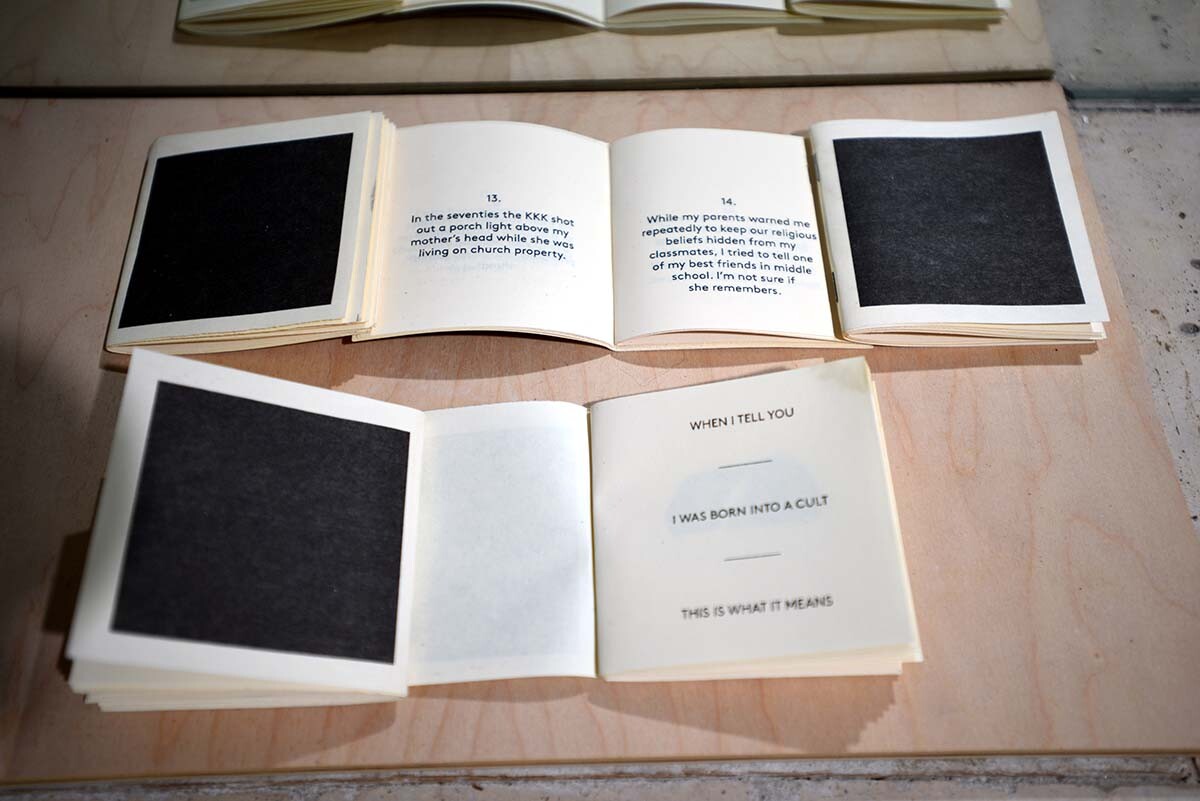

Akina Cox is a recovered “Moonie,” having been raised in the Unification Church. In her artist’s book, “When I Tell You I Was Born Into a Cult This Is What It Means” (2012), she shares what it was like; her fascinating history has also been documented in articles and podcasts. Her artworks often apply a strong feminist and social justice criticality to the biblical fables of her youth. Along with the artist’s book, the exhibition includes props and sketches from “The Book of Goliath” (2019), her shadow puppet play reinterpreting the myth of David and Goliath.

JP Munro had an entirely different relationship with religion growing up. His parents were liberal Christians who didn’t pay that much attention to the Bible, but he wished they did, because the imagery fascinated him from a young age. Identifying today as agnostic and expressing a sort of anthropological curiosity toward a number of narrative histories, his artwork often features dramatic renditions of biblical stories like “Suicide of Saul” (2017) and “The Temptation of Christ” (2012).

Dustin Metz was raised Roman Catholic and attended Catholic school through the eighth grade, but stopped going to church when he reached high school. Although his relationship with religion is not as fraught as that of some of the artists in the show, his imposing renditions of the Holy Bible are nonetheless two of the most charismatic works in the show.

Click right and left to see other works from the exhibition:

Two artists in the show do contribute devotional works. Buena Johnson’s stunning tableaux bring notable biblical passages to life and feature African Americans in prominent roles. And in a surprising turn, painter Celeste Dupuy-Spencer contributes several biblically themed works, two of which depict her own relatively recent baptism. While the prominence of religious scenes in the artist’s recent work has been attributed to her overall investigation of American society, Dupuy-Spencer suggested in a conversation with Hernandez that some kind of personal conversion had in fact taken place, and expressed great excitement for her work to be shown in a church. The exact nature of her conversion, however, was not clear.

A beautifully situated exhibition, “The Biblical Imagination” keeps the promise of its title, offering a re-imagining of religious art from an intricate variety of perspectives. Visitors to Missiongathering Church can also enjoy the bonus experience of walking the Irenic Projects Public Labyrinth, a meditative mini-journey designed and created by Hernandez using rocks sourced from neighbors.

“The Biblical Imagination” is on view by appointment only, at least through the end of December; contact Gregory Michael Hernandez at @exile.child on Instagram for details. Follow @irenicprojects on Instagram to be notified of upcoming events and future exhibitions.

Top Image: Edgar Arceneaux, “A Time to Break Silence,” 2014, video, installation view | Courtesy of Irenic Projects