How Can I Use Outdoor Spaces to Share My Art and Build Community?

“How to Change” is a limited series for “Southland Sessions” exploring the most critical issues facing Southern California culture makers in this pivotal historical moment. Each column will explore a question posed to a range of artists and culture workers, and include recommendations to address these concerns from a practical, action-oriented perspective.

Using Public Spaces?

For the fifth installment of "How to Change," I asked, "How are artists sharing their work and building community under socially distanced conditions that have moved art activities outdoors?” While the volume of activity is nowhere near pre-pandemic levels, the prolonged shutdown has seen many Southern California artists get creative about exhibiting their work in outdoor spaces. I spoke to a few who have organized shows and events this fall that are ongoing or can still be viewed online.

Alessandra Moctezuma is Director of the Mesa College Art Gallery and faculty in Museum Studies at San Diego Mesa College. This fall, she was challenged to come up with a viable final project for her students in the Museum Studies emphasis. Mesa College is a community college that seeks to create pathways to professional access for its students by offering a skills-building curriculum such as the hands-on first-semester practicum that Moctezuma teaches. She laments how, in spring 2020, “we had to shut our college gallery completely. We were just about to open an exhibition when the shutdown occurred, featuring four women artists,” including two based in Ensenada and Tijuana, Mexico. “It was ceramics and painting and sculpture. It was a really nice collaboration between artists in Mexico and artists here in San Diego. That was pretty sad that we had to just shut down completely.” Online programming on Instagram, virtual gallery tours, and a website were strategies that she used to keep attention on the exhibition remotely. “I explored some of that for my museum studies class," she explains. "I was thinking, I can't really do an exhibition in the gallery, and I'm not really so convinced about doing a virtual exhibit." Access for low-income students, who might not have broadband WiFi or computers with powerful processors, was also a concern. “[Virtual exhibits] are hard to navigate and, if you're on a laptop, it's really difficult. As a user, it is not so great.” The alternative of creating a website for the artworks, while more accessible, didn’t spark excitement. For Moctezuma, a curator and artist who got her start painting murals with Judy Baca at SPARC in Venice, and later went on to work for the MTA in Los Angeles as a project manager for public art projects, an outdoor site seemed an obvious solution.

Getting permission to turn the Mesa College parking lot into an art exhibition for a night was another matter. “I needed to go through a series of steps to get them to approve this because it involves people coming onto campus, traffic, police,” Moctezuma describes. “But the college, in the summer, did a drive-in graduation. And we've also been doing a monthly food distribution for our students who are food insecure, every month. And we also have WiFi access in the parking lots so students can park their car and utilize the college's WiFi for their classes if they need to.” She leveraged these precedents to persuade the administration to give permission for the exhibit. “They even gave me permission to have a few of the students come on campus, wearing masks, just outdoors, to help hang the exhibition.” Learning to install the artworks, write about them, and promote the exhibition are crucial elements of the hands-on curriculum. With 90% of the students based locally, the class was excited to work on a project that would allow them to collectively assemble on campus again, safely.

More Stories of How to Change

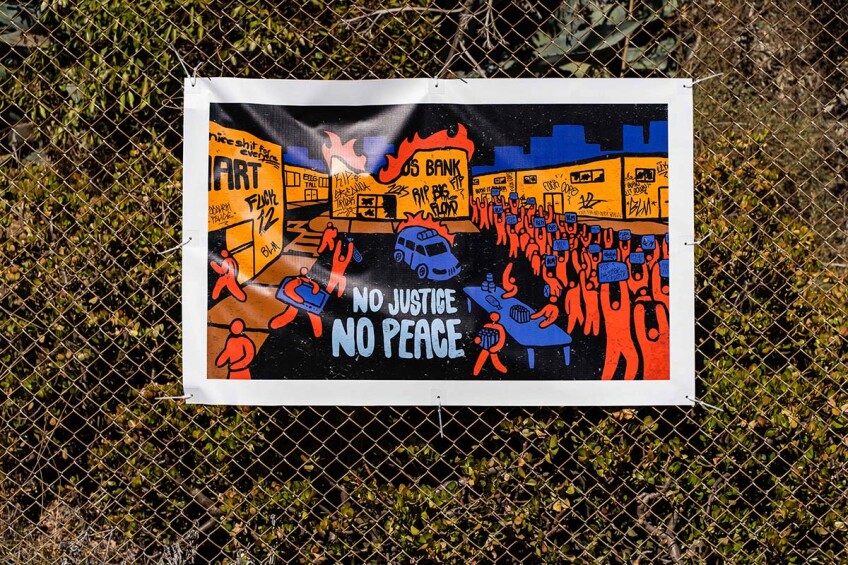

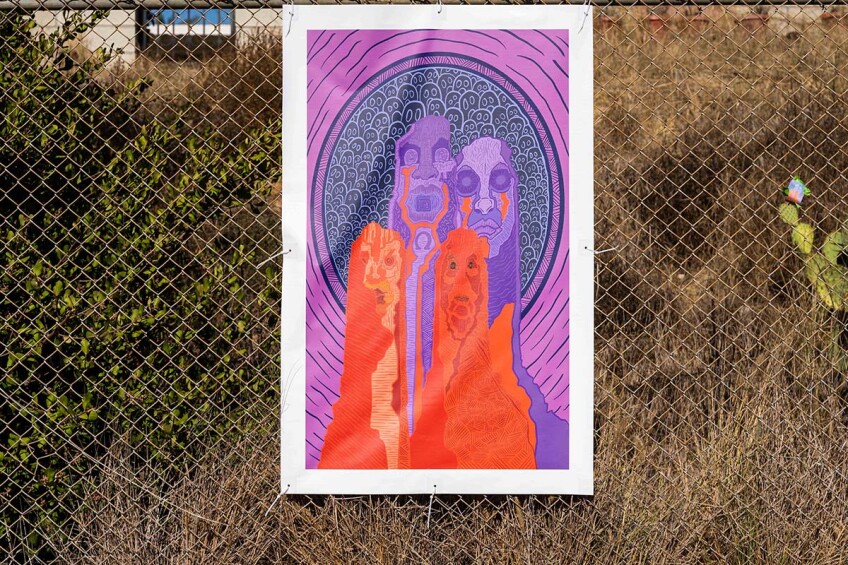

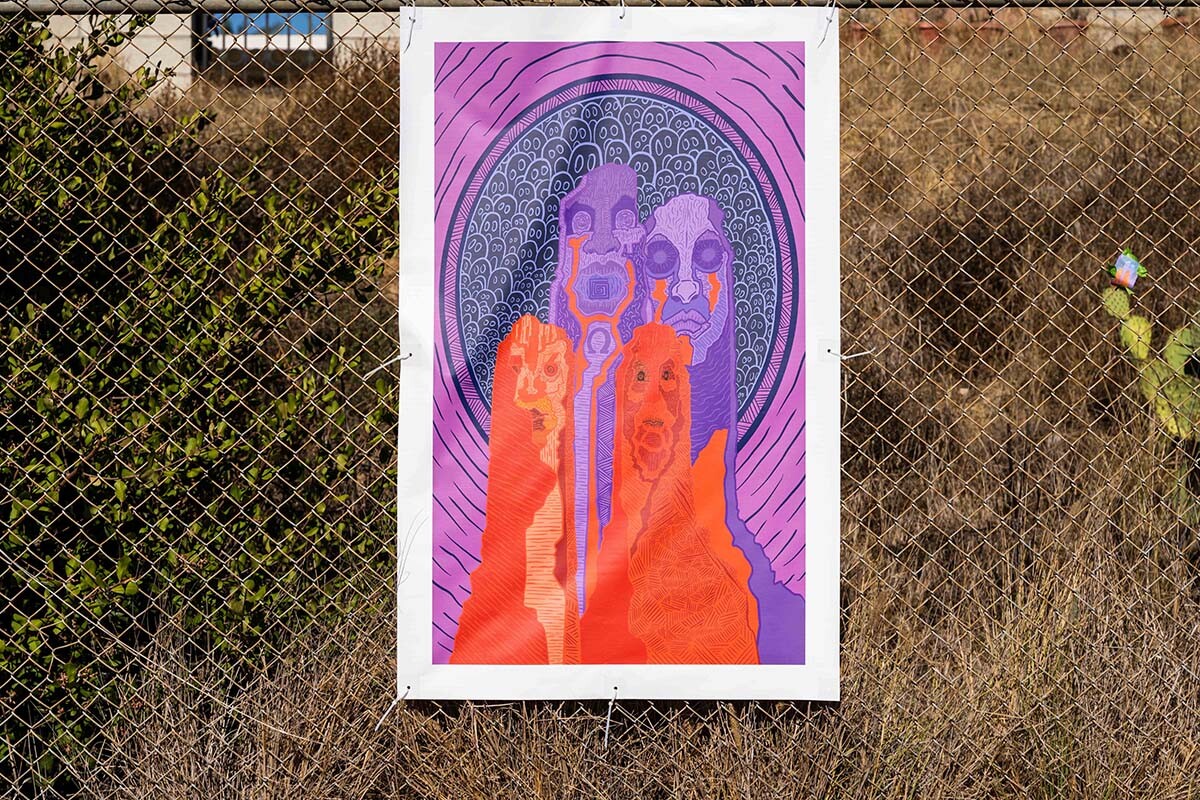

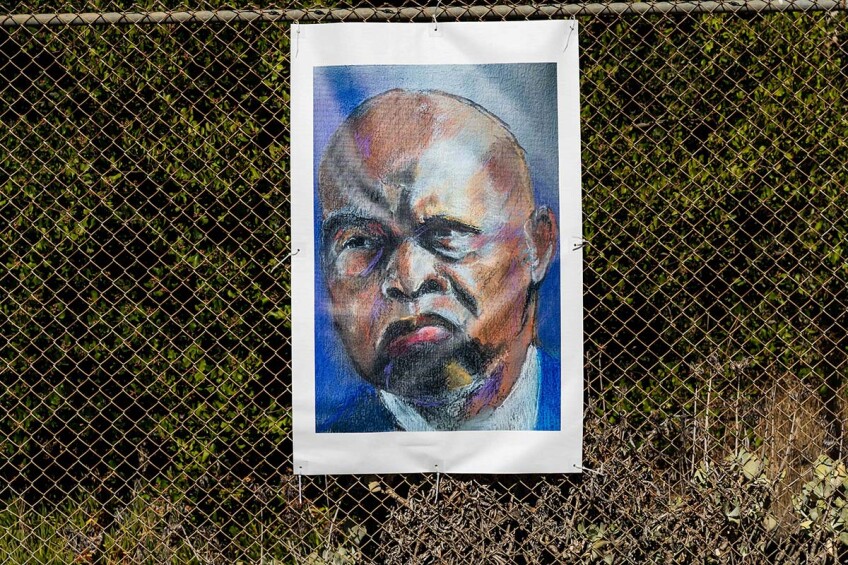

“Mesa College Drive-In: An Outdoor Art Exhibition" opened on November 13, 2020, with a drive-in reception that included a receiving line to greet attendees, as well as an audio tour explaining each artwork in detail. The works were printed on vinyl banners that the students affixed to a fence lining the parking lot’s perimeter. San Diego audiences can visit the exhibit in their cars until December 9. Says Moctezuma, “I wanted to orchestrate that event almost as a performance, a happening. What we did is we created a whole circuit for the cars to come through.” The event brought approximately 160 cars through on the exhibition’s opening day. For the students who were not physically present, including one in Texas and one in Berlin, “I actually narrated a Facebook live stream explaining what we were doing,” Moctezuma reports. “We also had a video of a panning shot of all their banners. So they could see it that way.” Though Mesa College primarily caters to San Diego students, its unique approach to curating in an undergraduate curriculum gives the program a broader reach.

Click right and left to see art from the Mesa College Drive-In exhibition:

The sense of connection that the event generated was felt by the student curators as well as the participating artists. “One of the artists in the exhibit whose work was selected is a young woman who has autism,” she explains. “She's a wonderful painter. And she had been so sad when everything shut down because she loves participating in exhibitions.” After the event, Moctezuma was thrilled to receive an email from the artist's mother. "When she came, and she saw people stopping by her artwork, and she was able to experience it, it broke down that distance that she had felt of being so far from people." Indeed, many artists are motivated to create art by the interpersonal connections that they discover when they present their work publicly.

One such artist is Warren Neidich, a conceptual artist and organizer who has spent more than half his time in Los Angeles over the past decade and is currently riding out the pandemic in East Hampton, New York. While getting to know the east end of Long Island last spring, Neidich hatched a public art exhibition, “Drive-by-Art (Public Art in this Moment of Social Distancing),” which spawned a Los Angeles edition co-curated by Neidich, Renee Petropoulos, Michael Slenske and myself. This fall, Neidich has teamed up with curator Rita Gonzales (LACMA), poet Joseph Mosconi (Poetic Research Bureau) and writer Andrew Berardini to present “5-7-5,” a series of text installations by local and international artists on the marquee of the Theater at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. At the Ace, “It's an old fashioned marquee with three sides,” Neidich describes. “And originally they had only wanted us to use the front, but then they got so excited about the project that now we're using all three [sides].” The first artist, David Horvitz, premiered his text piece in late September, while the last, poet Joyelle McSweeney, will present hers during the week of December 2-9.

Click left and right to see art from "Drive-By Art" :

Each week-long installation employs the Japanese haiku form of poetry, in which the first line contains five syllables, the second line contains seven syllables and the third and final line contains five. Mosconi designed a template that allows each artist to map out their own text installation according to the parameters of the marquee. Says Neidich, “The artists are given multiple ways that all three of the scrims can be used and the haiku gets kind of broken up and becomes fractionalized, because of the way it's distributed.” The visual form of the marquee, indelibly linked to stage performance and cinema, is repurposed as a literary medium. Neidich had been organizing projects of this nature in New York, including Exhibition 211 in 2009, and in Los Angeles, collaborating with LAXART and artist Elena Bajo, his partner, for “Art in the Parking Space” in 2011-12. “I don't consider myself a curator. I consider myself an organizer,” he explains. Acting as an organizer offers a freedom that institutional curating may not. Creating temporary and immediate public spaces within the increasingly privatized landscape of contemporary Los Angeles seems in itself like a destabilizing act.

Click right and left to see more work from "5-7-5":

Artist Rachel Yezbick understands the power of invoking public rights in private space. Yezbick was invited to create a performance for the MAHA Pavilion, part of the Bangkok Biennial 2020, which was curated by L.A. and Bangkok-based artist Prima Jalichandra-Sakuntabhai. Having never been to Thailand, Yezbick was asked to select a Thai performance artist as a collaborator from an open call. They selected Sikarnt Skoolisariyaporn, and the two exchanged tours of their cities with one another over long walks on video calls. Yezbick recounts, “Her work was also very much thinking about material culture, ephemerality, the detritus of things that are left behind, where do we find that within our own local communities. I had an interest in engaging with these places not through typical means — we're not going to go to Google Maps, we're not going to use images — all these things that are at our disposal to just understand a really quick representation of this place, but we're going to use each other's experiences to come to understand a personal exploration of these cities, of contested sites.” The result was an hour-long walking tour on November 11 that meandered from Pan Pacific Park through The Grove, following the route that Yezbick determined had been taken by some Black Lives Matter protestors during the May 2020 unrest that resulted in a police kiosk at the outdoor shopping complex being vandalized and set aflame.

Click right and left to see photos from Rachel Yezbick's performance in Los Angeles:

Los Angeles-based artist Prima Jalichandra-Sakuntabhai curated Yezbick’s performance for the MAHA Pavilion. They describe how “The idea behind the Pavilion came to me as a way to reflect on my own estranged relationship to my homeland of Thailand.” A typical biennial features prominent and often familiar artists and is intended to showcase the wealth of the host country for an audience of international tourists. "The representation of the country's identity itself is mostly shaped by the conservative values of the monarchy and the tourist industry,” they explain. “While the Bangkok Art Biennial replicates the format of the international art biennial as an additional influx of capital, investing in international big-name artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Marina Abramovic and Yayoi Kusama, disregarding contemporary art production in Bangkok by the local art scene,” the Bangkok Biennial was created by Thai artists to advance a counter-narrative: “Anyone can host a pavilion.” This approach informed the curation of the MAHA Pavilion. Jalichandra-Sakuntabhai describes how “by not flying the international artists to Thailand, I choose to deprive both artists and audiences of the promise of the exotic land.” Under quarantine, audiences were acclimated to online programming. “The virtual becomes a means, rather than a default, in bridging the gap between these two spaces and temporalities,” they assert. Since COVID spread in Thailand is extremely low compared to the United States, the conversation between artists sited in distant geographies and time zones became illustrative of the different approaches to public health and social order.

The pandemic created a sense of crisis that was compounded by personal events as well as public demonstrations of a political nature. “So it happened that both cities were undergoing and are still undergoing major protests,” Yezbick asserts. “Moreso, even in Thailand, now, where in Bangkok, it's gotten very serious there, and the protest for democracy outcome shifted to the police using live ammunition." Though the situation in Thailand appears more acute, with daily demonstrations to reform the Thai monarchy being met with state violence, the same time frame in Los Angeles witnessed Black Lives Matter protests and the refusal of President Donald Trump to formally concede the November election. “So we were kind of parallel to some degree,” they say, “in terms of being in states where dictatorial rule was really being imposed on the people.” Prima Jalichandra-Sakuntabhai offers more context: “Just as the Black Lives Matter protests have ignited conversations around racial inequalities and each of our individual complicity and infliction across the U.S. and Europe, Thai youths are gathering to end the military dictatorship and establish a true democracy. Both uprisings question the core of the country they are taking place in and the foundation of the current power.” Yezbick continues, “It got quite personal, at one point, [Skoolisariyaporn’s] grandmother passed and that came up in the piece. At one point, I got a positive COVID test. And I was relegated to my house.” The artists wrote letters to one another during this period that formed the basis of Yezbick’s script for the performance. So often in performance art, the body comes to the forefront, as it does in situations of illness and death.

Thinking of the protestors who attempted to evade arrest by diverting down the alleyway, Yezbick asks, “What are the aesthetics of retreat? What are the aesthetics of this politics of being pushed out?” The alleyway itself is not exactly private property, nor public, not clearly a space reserved for cars or for pedestrians.

Yezbick used physical intuition to determine the route that her performance ultimately took. "It was my imagination of what this route was for the Black Lives Matter protest, and I altered it from the route I took her on initially in that tour," they confide. "These protests start in spaces where it's okay to convene because there are few of these spaces. And you can get a critical mass in that space. Thinking about the proximity of The Grove right next to Pan Pacific Park in that neighborhood, it's so performative; it's so extreme." The spectacle of Christmas at The Grove, struggling to retain a buoyant atmosphere against a shuttered movie theater and closed restaurants and bars, added poignancy.

The question of who gets to use these spaces, and for what purpose, was central to Yezbick’s performance, which was attended by a limited audience of ten masked and distanced guests. The group was small enough not to attract much attention in the park or the mall, but in the alleyway off 3rd Street where the tour concluded, ten was a crowd. “A little bit of a heightening of that violence, that already we’re condensed and compressed and that we have to move through this space that already has the strict rules and adherence as to how we can move and what what we're allowed to be there for,” is what they sought in choosing The Grove as a site for a reading and a performative gesture.

Thinking of the protestors who attempted to evade arrest by diverting down the alleyway, Yezbick asks, “What are the aesthetics of retreat? What are the aesthetics of this politics of being pushed out?” The alleyway itself is not exactly private property, nor public, not clearly a space reserved for cars or for pedestrians. Yezbick was interested in this liminal space and in its unsuitability as a route of escape. “It's really not that much shelter. It's really not enough space away from the main drag to get away from police cars. They can still come right there. And you can't hop the hedge into the private property. So this intense construction on the body — where we're allowed to be, how we're allowed to move — was something that I kept thinking about.” Unsettling comfort is essential to their work. “Discomfort for the viewer, for myself as well, there's this other space of injecting something that's not normally injected” into sites reserved for specific public or private uses. This unsettling serves to “help lift the veil, to help people from whatever walk of life they're coming from realize that there's an entire theater already at play.” Performative interventions in public space make unwitting audiences of passers-by, who may not understand what they see to be art, but experience the unsettling nonetheless.

For many in the arts, social contact with a community of peers holds much of the appeal of our line of work. “I miss people so much,” Alessandra Moctezuma confesses. “I’m somebody who every weekend is at three, four art openings.” Outdoor art activities, which are usually temporary and often event-based, can’t fill the void left by museums and galleries closing completely, but they can resurrect the sense of connection and collective purpose that indoor art venues often generate through events. Putting art outdoors also carries a political charge that can be unexpected, as when Warren Neidich placed a sign, “Artists are Essential Workers,” outside Guild Hall in downtown East Hampton, New York earlier this year. He reports, “The town did not feel it was an artwork, even though it was on the grounds” of a space that shows contemporary art, and the work had to be moved to a less public location outside The Fireplace Project. Whether more or less visible, the works are no less effective, as Jalichandra-Sakuntabhai explains: “The scale of the audience reflects on the intimacy of the piece.” Even when engaging a deliberately limited audience, as Rachel Yezbick chose to do, the charge can be potent. By stretching the boundaries of what is permissible in outdoor spaces, undertakings like these infuse art viewing with new excitement.

Top Image: "Vertical Scuttle," Clay, underglaze, and wire, 2020 by Mirena Kim | Courtesy of the artist