COVID-19 and Anti-Racism Movements Create New Urgency for Working Artists

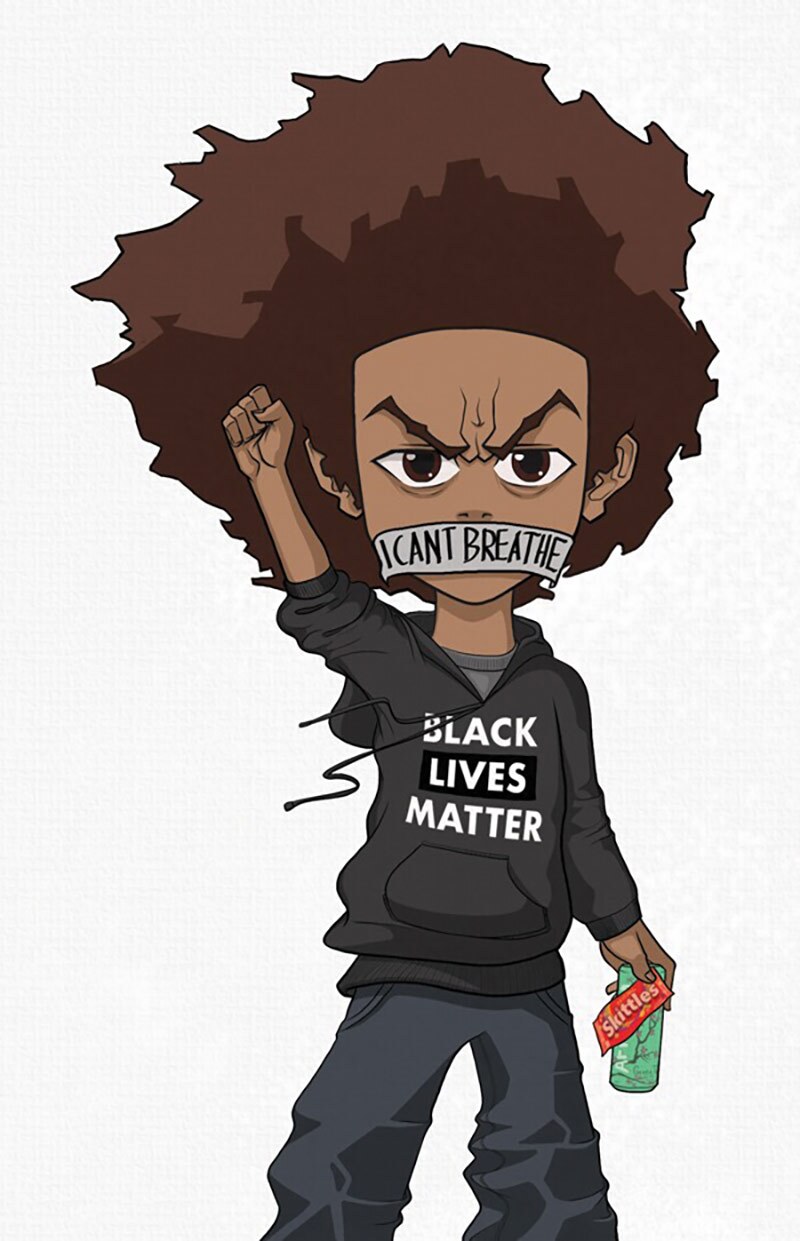

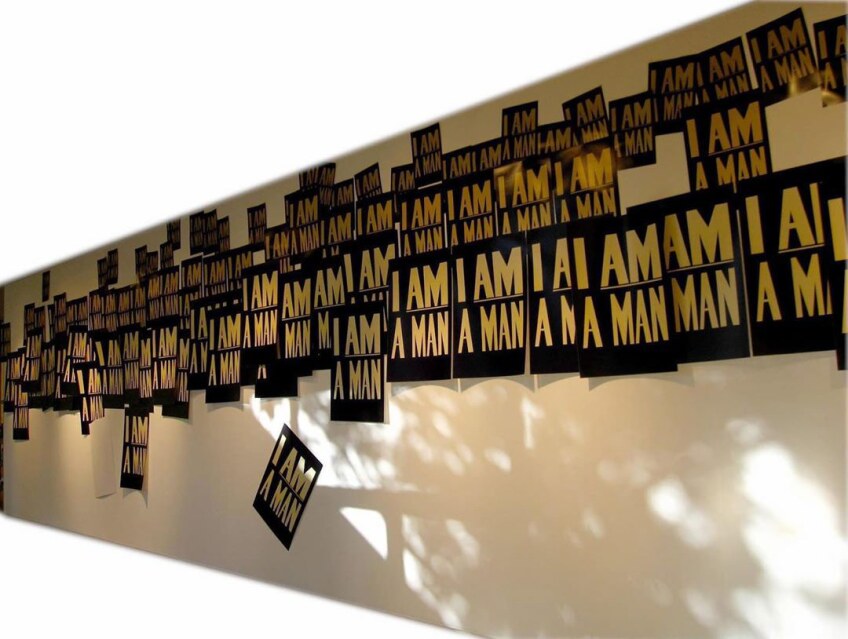

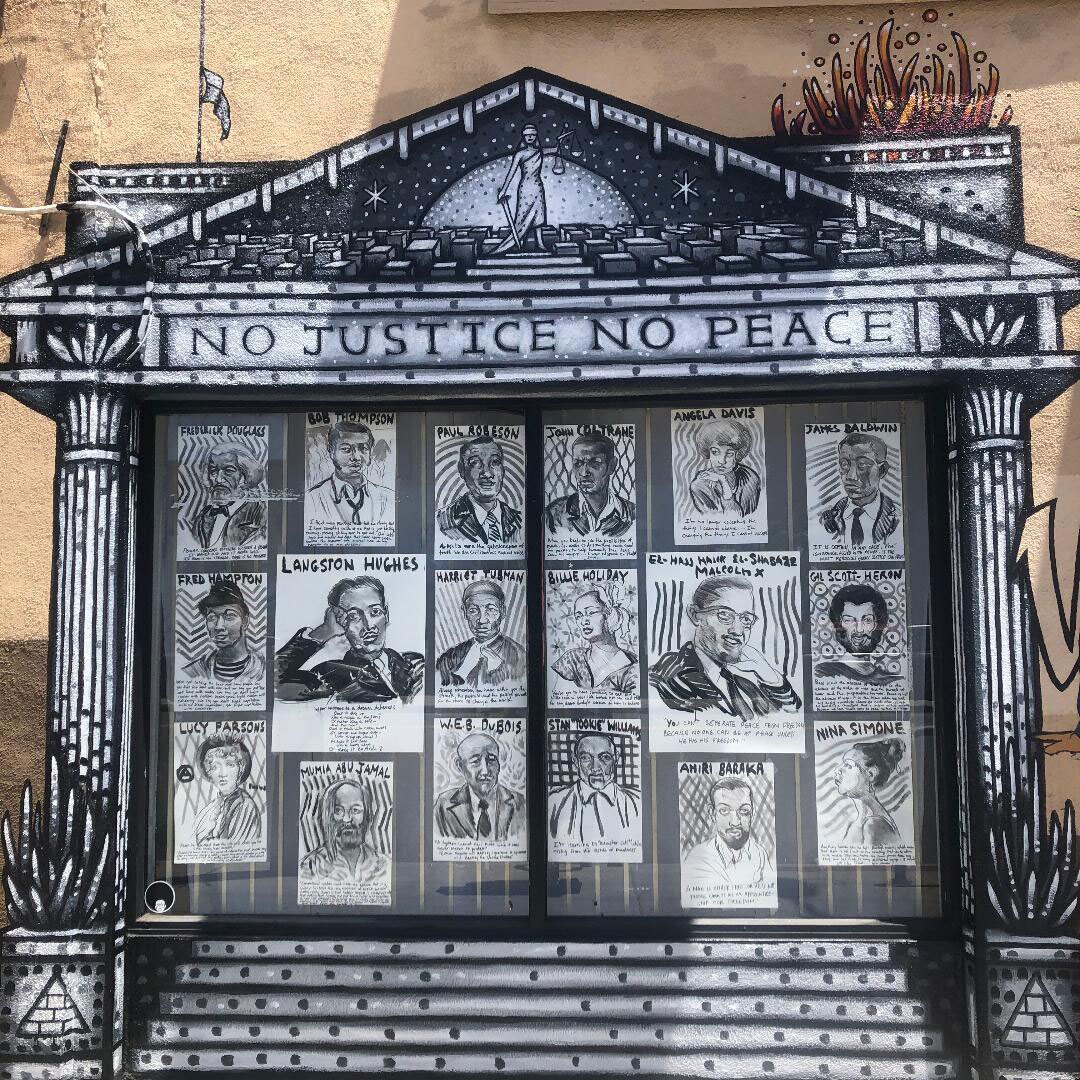

In recent weeks we’ve seen an outpouring of artworks on social media and in the streets responding to the protests around the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and myriad other Black victims of police violence. Some artists have created memorial portraits, murals or performances; others have offered art in exchange for donations to bail funds and anti-racist organizations. Still others have created works critical of the current administration or acted as archivists, collecting documentation of public artworks and protests (see below for a slideshow and links to local art responding to the current moment).

Some artists are engaging with issues of police brutality and systemic racism for the first time; others, especially Black artists, see this time as a pivotal moment for issues they have been dealing with for years.

“Black artists have historically created their art as a form of protest,” wrote Terrell Tilford, founder and creative director of the West Adams gallery, Band of Vices, in an email. For artists like Robert Colescott, David Hammons, Betye Saar, Kara Walker and many others, interrogating racism and representation has been a cornerstone of their work. This moment, however, may be a little bit different. “The world has now responded more profoundly than ever before,” wrote Tilford, “Many artists cannot focus, concentrate, nor work from this current state. It is crippling, it is arresting. So they, like so many others, have walked out of their studios and they are in the streets.”

L.A. artist Forrest Kirk has joined the protests, but has also found the current moment artistically invigorating. “I haven’t really had much of a slowdown in my work,” he said, “Because for me, it’s only intensifying the expression in the work.”

Kirk’s 2018 exhibition at Chimento Contemporary in Crenshaw featured paintings and sculptures, both graphic and fantastical, investigating the racist and abusive attitudes of police toward Black people. He has an upcoming show at Parrasch Heijnen Gallery in Boyle Heights in July.

One of his recent paintings, “A Bird in the Hand,” combines references to Ralph Ellison’s novel, “Invisible Man” and the COVID crisis. “I’m making work that’s reflective of now, but not being completely didactic,” he said, “I’m not doing a direct mural to Breonna or George Floyd, but they’re in the work.” He likens his art to what he calls “reality rap.” “I see my work like Public Enemy, like N.W.A., like Eric B. and Rakim,” he said, “I grew up being told this is the truth.”

When asked if he sees his work as a protest, he replied, “I don’t think, per se, it’s an artist’s responsibility to protest in their work. As a human being I think people should take action and stand up for something, but as an artist, that’s up to you individually.”

For lauren woods (whose name is written all in lowercase) art and activism are one and the same. The Dallas-based artist has been working on “American Monument” in collaboration with Kimberli Meyer, an independent L.A. curator, since 2018. The interactive installation exposes and analyzes police and legal reports, witness testimonies, 911 calls and body and dash cam videos associated with instances of police brutality. It was on view at UC Irvine’s Beall Center for Art + Technology until it was shuttered due to the COVID crisis. Before that, the ongoing, nomadic project also appeared at Cal State Long Beach’s Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum.

“American Monument,” said Meyer, “was always meant to be not something that represents the problem of police brutality against African Americans, but really acts as something which can help to change and actually help support the movement.” woods sees no distinction between her artistic practice and the organizing she’s currently doing for a coalition under the banner of In Defense of Black Lives. Focusing on messaging to defund the police has facilitated “really starting to understand different frameworks for different types of futures and I think that all helps to feed into the goals and purpose of ‘American Monument,’” she said.

For her, the Western notion of artists as lone, individual geniuses is counterproductive to collective movements like Black Lives Matter. “It makes it really difficult for artists to actually practice in this socially engaged way because a lot of the labor goes unseen. It goes un-praised. You don’t get grants for it. You don’t get a commission to make a sculpture in a park for it,” she said.

Instead, she and Meyer think artists can support the movement by contributing their expertise in communication and aesthetics. They cite the large-scale writing that has popped up on city streets as an example. “All of this writing on the public space is attacking the white design imaginary — how we design public space, how we design things like the color schemes,” woods said. “Our tool is communication. That is literally what’s driving this moment right now. Black Lives Matter is successful because of its ability to spread a message with great aesthetics.”

Click through below to see how L.A. art is responding to the Black Lives Matter movement.

And here a list of links — in no way exhaustive — to online projects, listed alphabetically by the artists' last names:

Artists are raising money for BLM-related causes with #artforblacklivesmatter on Instagram.

Hugo Crosthwaite created this powerful Black Lives Matter animation on Facebook.

Yrneh Gabon created this affecting performance, A GARDEN OF THORNS, for Drive-By-Art.

Artist collective SPARC made this amazing parachute to unfurl at protests.

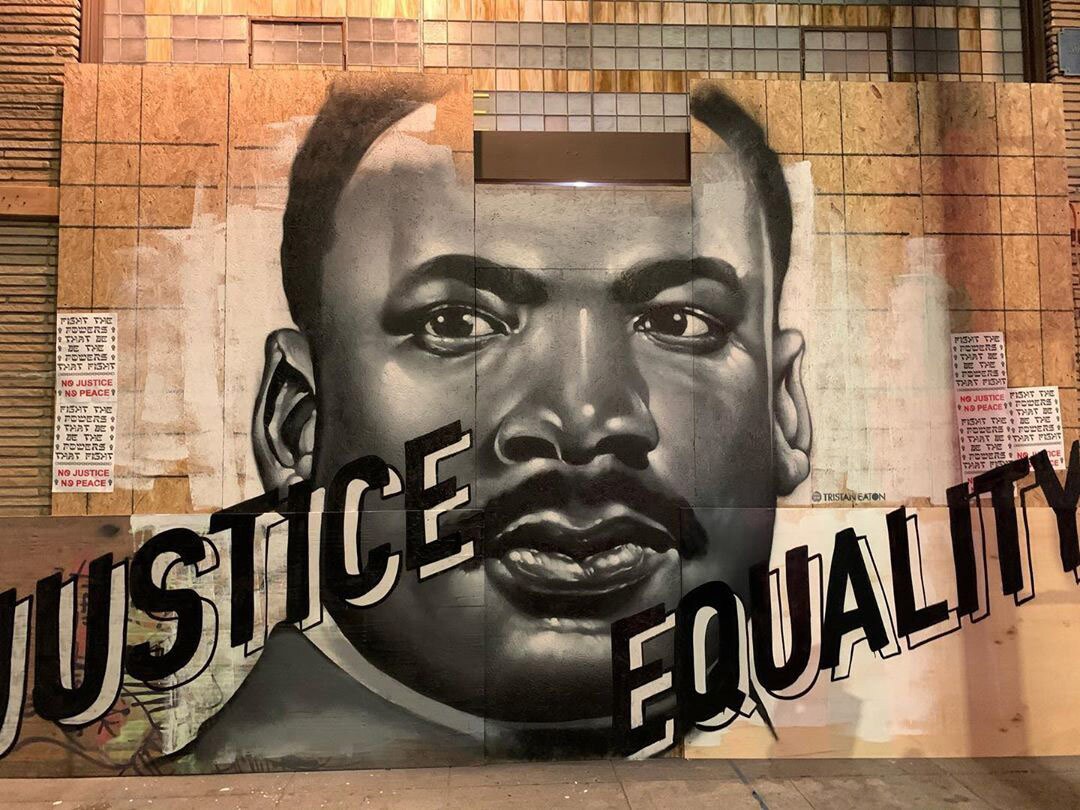

Top Image: Tristan Eaton, mural at York Blvd. and N. Ave. 50 in Highland Park, June 6, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.