Band of Vices: Disrupting the Art World for Two Decades

At the Band of Vices (BoV) art gallery in South L.A.’s West Adams neighborhood, two Black curators and longtime friends, Terrell Tilford and Melvin A. Marshall have been toiling for years to provide a platform for and amplify the voices of artists, many of whom are women and people of color. In commemorating their 21st year of organizing art shows together and during a time of reckoning regarding racial injustices, the duo has co-curated an exhibition that features four artists depicting their experiences as Black men in America.

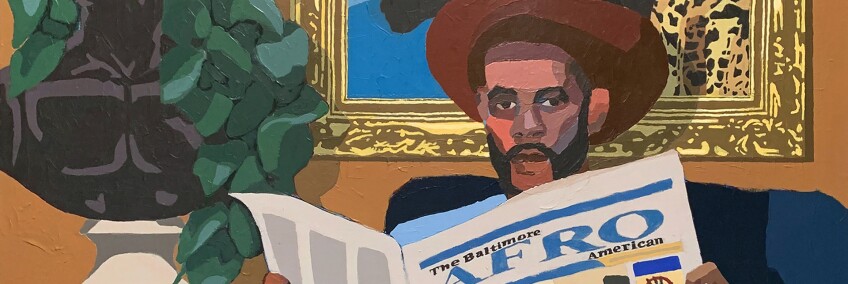

“KANGS,” which is on view at BoV through Dec. 12, centers on artwork from Andrew Gray, Idris Habib, Tommy Mitchell and Khari Turner. The exhibition touches upon themes of identity, systemic racism and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“It’s under the backdrop … that we have seen this story so many times before,” said Marshall, BoV’s senior curator and partner, in regards to the killings of Black people by the hands of police. “But now, what kind of country do we want? And how many more times do we have to go through this? And how many more Black bodies do we have to accumulate to change this narrative?”

Tilford, BoV’s founder and creative director, reflected on the recent deaths of Kobe Bryant, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and how that led the gallery to wrap up this year with “KANGS.” “These four young men are creating artwork, not out of anger, but out of an act of defiance, that they're standing their own personal ground,” Tilford explained. “They’re saying, ‘My voice matters in spite of all of this. You can put your knee on our necks, but we are not going to allow our overall spirit to be broken. It may be bruised, but still we rise.’”

Tilford and Marshall, both 51, work in synchronicity. Tilford, a veteran actor who's performed on T.V. series like "Switched at Birth" and "One Life to Live," has been a longtime art collector with a knack for discovering new and emerging talent. Marshall, an art historian and collector with two Master’s degrees in contemporary art and art history, writes about the artists for their gallery as well as curates exhibitions.

“I wanted to get to know more people, more artists who I'd never heard of, so that I could write about them and explain to the world why they should be a part of the artistic canon,” Marshall said.

Marshall, who previously worked on Wall Street, considers himself and Tilford as “unicorns” in the art world. In finance terms, “unicorn” is used to describe privately held startup companies with a value of over $1 billion — a rarity. “So it is with this idea that I termed us possessing the qualities of being unicorns in the sense that finding two African American curators who have been collaborating and co-curating exhibitions for over two decades together is as difficult to find as a mythical unicorn,” he explained.

“We have had decades of success in spite of the lack of visibility (this invisibility trope is one that we fight so hard against when it comes to promoting our artists, and it is one that is a common theme in Black literature such as in Ralph Ellison's ‘The Invisible Man.’ So, we are far from surprised that it has happened to us as well in the art world). I truly feel like we are just getting started, particularly because the art world has recently begun to ‘discover’ the contributions that so many African American artists have made to the art world culture.”

Click right and left to see works from their current exhibition, "KANGS":

The birth of BoV

Marshall was in the middle of getting his Ph.D. in art history and curatorial studies in the U.K. when he received a call from Tilford about launching BoV in West Adams. It was the rebirth of his Tilford Art Gallery in Mid-City that ran from 1999-2010. Tilford told Marshall he needed him to quickly fly out to L.A. to start writing about the gallery's artists. "[I said,] 'Melvin, you have four months, and I need you back right away. And I threw up the bat sign, and Batman showed up," Tilford recalled.

Marshall went on a sabbatical for his Ph.D. and came out to L.A. BoV opened in 2015, and he's been here since. The team has since represented accomplished artists like Monica Ikegwu, who paints striking portraitures of African Americans; and Grace Lynne Haynes, whose paintings have recently appeared on The New Yorker, like her portrait of Sojourner Truth, a Black woman rights activist and abolitionist.

Chelle Barbour, an artist also represented by BoV, noted how her career, as well as others, grew soon after they got involved with the gallery. “They catapult you into a place where you get greater public exposure, and for every show that they curate, you just become more and more … well known in your work,” she said.

Barbour, who met Tilford in 2018, added that one of the team’s greatest assets is their ability to locate new talent within L.A. and around the world. “At first, a lot of people thought that they were going to be a Black gallery that supports just Black artists, but they ended up being an art gallery that is more expansive; this year, it's very inclusive. They're becoming more successful because of [them being] inclusionary. … They believe in diversity.”

Tilford echoed these sentiments. “I like to think that, for the most part, while the majority of artists that we show are artists of color, we’re looking for fearless, thought-provoking artists who are willing to take risks, artists who are willing to say something unapologetically within their artwork.”

About 90% of BoV’s artists are women, many of which are in the U.S. and some abroad. BoV didn’t particularly seek out women artists, but rather, brought them into the fold organically because they were finding their artwork to be especially dynamic, according to Tilford.

“They're really good male feminists because they are very supportive of women,” Barbour said of Tilford and Marshall. “You never feel like they're taking advantage of you. They respect female artists, and as Band of Vices, they're fabulous. And they support male artists as well.”

Kaye Freeman, an L.A. artist by way of Australia, met Tilford in 2017 when she visited the gallery. She fondly remembered Tilford introducing himself to her when she walked in, and he was friendly, something that she found refreshingly different from other gallerists.

In April during the pandemic, Freeman’s work was featured in BoV’s first digital exhibition, in a show called “Further from Heaven.” “It's about vulnerability and the female form and all that sort of stuff,” Freeman said. “And they really get it, like I don't have to explain anything [to them]. They're really supportive. I've been around [in the art world] for a long time, and [with] male gallerists, it's really unusual to get that level respect. They talk to you in a really respectful way, and they really respect my work. And I just really appreciated that.”

Freeman noted that the team has created a family-like atmosphere, one in which they’re really interested in “cultivating art and nourishing the community.”

March this year, Barbour was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. When Tilford and Marshall found out, Barbour said they asked what they could do to help her. They held an auction for her artwork, and in turn, she sold several pieces. They gave her all the proceeds so that it could help with her medical bills.

“I'm just constantly impressed with Band of Vices,” Barbour said. “You go into a situation not knowing where the journey is going to take you, and this journey has been profoundly growth-oriented and positive.”

When Melvin Met Terrell

“We met when we were both at [University of California,] Berkeley together. Melvin loves to tell people that he was my first boss,” said Tilford, laughing.

They were both students at UC Berkeley in the late 1980s, with Tilford studying theater acting and English, and Marshall molecular biology. Marshall was the student supervisor in the men’s locker room, and as they handed out towels and water bottles, they instantly clicked over their love for art.

Tilford, an L.A. native, recalled first being affected by art when he visited Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s King Tutankhamun exhibit in 1978. “As an [eight]-year-old, little Black boy here in Los Angeles, who hadn't been exposed to a whole bunch of stuff, to then be thwarted into something that had such a profound visual effect on me, within one year, it sort of really tweaked my eye. Suddenly, I began to see a world that was greater than what I had grown up with just on my street, or in my little urban neighborhood.”

When Tilford was 15 years old, he was cleaning out his mother’s apartment garage and discovered a set of original drawings and paintings that he was amazed by. He found out that they were his brother’s works of art that he had drawn 20 years ago. One particular illustration that called out to him was of actress Tamara Dobson in the 1973 film “Cleopatra Jones”; Tilford remembered Dobson was drawn with a big Afro while holding a gun.

Tilford asked his brother if he could have it, and then he got it framed and hung it up on the wall. His brother, whom he considers his first superhero, walked in the room and saw the framed image. “To see him look at his work validated in a different way and then presented on the wall, it just began to engage a conversation,” he said. “And it began to shift things a little bit in the conversations in my home, and we began to look at things a bit differently.”

That would begin Tilford’s love affair with collecting artwork. He started with posters, then as he had more money, he moved up to prints, sometimes asking galleries to allow him to go on payment plans. He eventually began buying original artwork.

Marshall, a New Orleans native who moved to the Bay Area with his family when he was 10, was on a similar trajectory. When he attended UC Berkeley, he visited a friend’s home that was filled with art. Marshall, who had grown up driving his family crazy collecting grasshoppers, earthworms and snakes, didn’t know at the time that people could collect beautiful paintings. “I think that was the bug for me,” he said.

Marshall bought his first piece of art as he was leaving college. He ended up veering off the path of his science degree and working as a foreign currency trader for J.P. Morgan. He traveled around the world for work and visited a slew of art museums along the way. He began collecting African American art, and under the tutelage of his mentors, like the late artist, scholar and curator David C. Driskell, his collection grew. Marshall started collecting African American art books, and today has a collection of 400-500 books.

“My curatorial journey has been about an unspoken, unrecognized goal centered on correcting the notion that white people's art matters more and somehow is better than Black people's art,” Marshall said. “My journey has been to disabuse the world of this falsehood, this fallacy.”

While Marshall was on Wall Street, Tilford was out in New Jersey working on his MFA at Rutgers University. Tilford would come up to visit Marshall in New York as often as he could. In 1998, they had their first venture together, selling prints. By the next year, they organized their first art show in Midtown Manhattan, in which they honored their mentor Driskell, who died in April at age 88 due to complications from COVID-19.

The event took place on a stormy evening, but just as Marshall was convinced nobody would show up, the guests started pouring in as quickly as the rain. “The real takeaway from that evening was, it's like the ‘Field of Dreams’ thing: If you build it, they will come,” Tilford said. “And that has been tried and true with every version that we've done of this over the years. But the initial validation was that evening that there was such a hunger, such a desire, and such a willingness [for art] that people did whatever they could to get there.”

In the ensuing years, Tilford and Marshall would do pop-up shows in loft spaces and homes in New York, Oakland, San Francisco and L.A. Haitian-born artist Francks François Deceus, who met Marshall at an art fair in New York in the early aughts, recalled doing a pop-up show with the duo at a loft space in Oakland in 2001 before pop-ups were even a thing, he said. “The show was very successful and a lot of people came out,” Deceus recalled. “And it was the beginning of the beginning sort of thing. And that paved the way for a long-lasting relationship and collaboration.”

21 years of growth

“If you think about art galleries, it’s very elitist,” Marshall said. “Not for us.”

West Adams, where BoV is located, is a low-income neighborhood composed of 56% Latino and 38% Black residents. Tilford remembered seeing a Latino family walk by BoV; the kids were curious about the gallery, while their grandmother seemed hesitant. He walked outside and encouraged them to come in and experience his gallery.

“I want people to know that no matter what you are included,” Tilford said. “How many of us actually have had the good fortune of growing up with an art gallery in their neighborhood? I can't imagine the effect that it would have had on me from that standpoint. … That’s a real gift to be able to share [art with] people who don't know or understand the protocols or know the rules or just don't feel included because there’s supposed to be this hierarchy in the art world. And what we're trying to do is disrupt the model.”

BoV is about taking the pretension out of galleries, to make the experience more collaborative in regards to working with artists and with other galleries and museums. They try to learn from their artists and partnering gallerists as much as they try to offer up any knowledge they have, Tilford said.

Over the past 20 years, Deceus has seen the duo grow in their exhibitions. “It’s become more conceptual,” he said. “You improve with time, and you start to narrow down your points of interest and become more specific and clearer in terms of the story you're trying to tell. That's the biggest thing that I've seen, in terms of clarity and narrative."

Tilford and Marshall’s hard work is paying off. Tilford said that earlier this year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York contacted them asking for a copy of every one of their art catalogs so they could use it as archival material.

“Over the years, I've come to see ourselves as culture workers,” Marshall said. “What we're learning is that what we're really doing this for is the culture. It is not self-aggrandizement or making a million dollars. That’s not why we're in this. I left a job [on Wall Street] where I was able to do that. I find that the work that we're doing here, it's really bigger than us.”

Top Image: Andrew Gray's "Portrait of a Collector," 2020. Acrylic on canvas. | Courtesy of Band of Vices