Iconic L.A. Buildings That Were Saved From Demolition

Los Angeles is probably more full of stories of loss – historic buildings demolished– than stories of preservation.

Many structures that are threatened never get a fighting chance, fall into irreversible disrepair, and are eventually razed and even forgotten.

Paper sometimes goes up in flames. Wind blows trees down; trees fall. Things happen. People change their minds. But rather than dwelling on what we’ve lost to demolition, development, or acts of God, why not celebrate the places we almost lost… but didn’t?

Because sometimes if you raise enough of a ruckus and throw a big enough fit, you can actually save a precious historic, cultural, and community resource – even if it ultimately ends up getting repurposed for something else.

Here are five of the best preservation success stories in L.A.; places that were either resurrected from the dead or reincarnated as something entirely new.

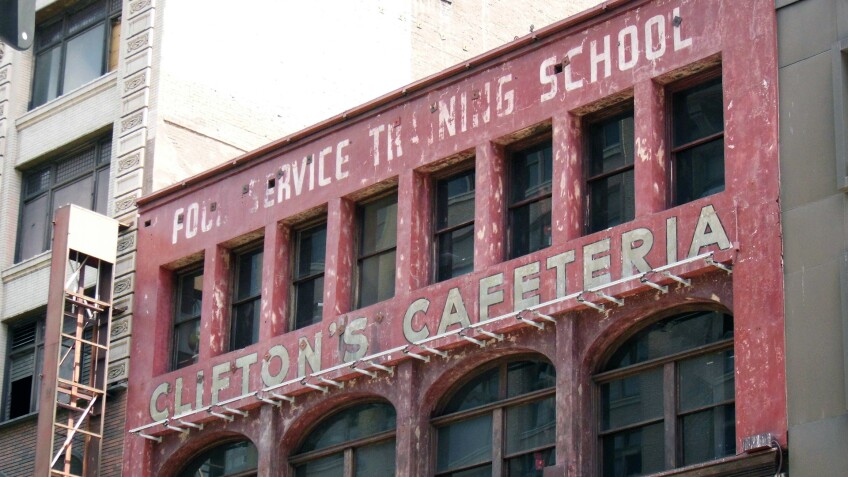

1. Clifton’s Cafeteria, Downtown

There used to be several locations of what was known as Clifton's Cafeteria, with branches as far flung as the Valley and Orange County (as well as the Clifton’s-run Pacific Seas tropical paradise). But the only one to survive is the forested “Brookdale,” the second one in the chain, now rebranded Clifton's "Cabinet of Curiosities." First opened in the 1930s, it operated continuously until it was closed for renovation in 2011. After that, no one was really sure if Clifton’s would ever actually come back. For four years, scaffolding and construction barriers were all anyone could see, aside from the terrazzo sidewalk design that tells the story of L.A., which was just peeking out a little bit. But then, a façade that had been added to the original frontage was removed, revealing the original Clifton’s lettering underneath – and L.A. let out a collective gasp. Under the direction of its new proprietor, Andrew Meieran, the Clifton’s restoration effort completed, and the new Clifton’s opened in 2015.

Everything there is big and bold, from the (fake) giant redwood tree in the middle of the dining room to the taxidermied beasts. For those of us who missed its prior incarnations, there are reminders everywhere. Souvenirs, memorabilia, collectibles, and other ephemera are displayed in museum-grade glass cases. At its heart, Clifton's wasn't exactly fine dining. It was a cafeteria that offered comfort fare and, perhaps most famously, Jell-O.

The Jell-O stayed for a while at this new Clifton's – but as of the end of 2018, the former cafeteria stopped offering food and operates solely as a nightclub on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights. That’s not exactly what Clifford Clinton had in mind when he founded Clifton's and offered meals on a "Pay What You Wish" basis… but I think he’d be happy that people are still coming…and that one of its neon signs has been burning continuously probably since 1935.

Bonus: Formosa Café, West Hollywood

Until it closed in January 2017, the Formosa Café was one of the most stalwart mainstays of Hollywood nightlife, located across the street from the movie lot that was, at one time or another, Pickford-Fairbanks Studios, United Artists Studio or Samuel Goldwyn Studio. In the early 1990s, its lease expired – and as plans to expand The Lot attempted to encroach on the restaurant's footprint, it was threatened with demolition. In 2004, the developer of the "Gateway" shopping mall next door agreed to build around it after being wooed by its charms. The 1933 Group has since taken over ownership of the historic landmark and is working to restore the oldest section of the restaurant, the train car – PE #913, in service from 1902 to 1906 – before reopening to the public.

2. Wiltern Theatre, Koreatown

If the case of the Wiltern Theatre teaches us anything, it's that something that's very, very far-gone can still be saved. In 1979, despite having been placed on the National Register of Historic Places, the former Warner Western Theatre was almost lost. It wasn’t just threatened with demolition – demolition had already been approved. The demo crews had arrived. The furniture (including the built-in theater seats) had been sold off. There was a giant hole in the ceiling and two feet of water covering the floor. And, like a scene out of a Hollywood movie, preservationists threw their bodies as a human shield to save this beloved Art Deco building. It was one of the earliest preservation victories of the newly formed Los Angeles Conservancy.

Thanks to developer Wayne Ratkovich and architect Brenda Levin, this bygone movie palace from 1931 was able to bounce back and operate successfully as a popular concert and event venue – with many of its original details and ornamentation preserved (or, at least, reproduced). Many Art Deco features have been repainted to their exact original specifications. The centerpiece of the lobby is still the rotunda, which was first restored in 1984 during the multi-million dollar effort to reopen the theater as a performance venue. It’s just now lit by LEDs. Located at the corner of Wilshire and Western, the Wiltern is now operated by Live Nation and open for concerts, movies, and dance parties almost every night of the week.

3. Cinerama Dome, Hollywood

When it was built in 1963 under the direction of Welton Becket (in less than five months), the geodesic dome shape of the Cinerama Dome was as groundbreaking as it is today. It's still the only theater of its kind in the world. And because the 70-foot dome is such an oddity along Sunset Boulevard, refusing to be dwarfed by the CNN tower that sprung up two blocks down in 1968 or even the big Walgreens that's been selling sushi across the street since 2002, it makes for a great advertising platform for the latest release starring Shrek, Spiderman or the Minions. (That may be what saves it in the long run.)

Modern-day restaurants, retailers, and of course a parking structure have been built up around the Cinerama Dome – but fortunately, they haven't consumed it entirely. (It did, however, close for two years and reopen in 2002.) Still operated by Pacific Theatres, The Dome is now part of the Arclight movie theater complex, showing both first-run releases, red carpet premieres, and repertory selections on a screen that measures 32 X 86 feet and is curved at an angle of 126 degrees – a perfect canvas for cinematic extravaganzas like "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World," which was screened as part of the theatre’s grand opening and has returned a few times since.

4. Central Library, Downtown

The last work of American architect Bertram G. Goodhue, the 1926 completion of Los Angeles' Central Library interweaves 20th century architectural style with classical influences and references of ancient cultures. It persists as a major landmark in L.A.’s downtown, adjacent to Bunker Hill. But it's amazing that it’s managed to survive at all – in any form. In the mid-1970s, Central Library was slated for demolition, but it was preserved in 1983 as a result of community efforts and the Los Angeles Conservancy. But it wasn’t yet in the clear – because two fires (both suspected arson) raged through the library's upstairs, near the Lodwrick M. Cook Rotunda upstairs (in the area now designated as the Teen 'Scape) and destroyed much of the library's collection and some of its interior decorations.

The windows shattered and had to be replaced. The magnificent globe chandelier (which represents the solar system) survived, though other lighting fixtures had to be replaced with reproductions, including the Art Deco lamps in the Children's Literature Department, which also houses a number of California history murals (The Landing of Cabrillo at Catalina, etc.). The Dean Cornwell murals that rise to the ceiling have since been restored and cleaned. Now, despite the devastating fires, the library also sports a new wing and a full rehabilitation. And – as an institution focused on printed matter, a threatened and nearly defunct format itself – it takes its preservation seriously. It saved its card catalog cards and has reused them to line the walls of its elevators.

Bonus: The Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills

Beverly Hills Waterworks wasn’t just the first municipal water treatment plant on the West Coast and the first civic building of Beverly Hills. Its construction (and the formation of the Beverly Hills Utilities Corporation) allowed one of the earliest planned communities in Southern California to stay independent of Los Angeles. Because Beverly Hills had its own water – and, though it was sulfurous, a supply that could be filtered, purified, and used – it wouldn't need to be annexed into L.A. The Waterworks opened in 1928 to much fanfare, and it successfully processed water for Beverly Hills for nearly 50 years. But it closed 1976, when Beverly Hills began buying its water from the Los Angeles Metropolitan Water District.

Just five years after having been damaged by the Sylmar earthquake, the Romanesque and Moorish-influenced building was rendered obsolete. And for 10 years, it stood abandoned – and vulnerable to vandals and vagrants. Even vandalized, the property had retained integrity from its period of significance – including an ecclesiastical facade (a "cathedral of water," as it were) and a bell tower that hid the chimney that burned off the sulfur in the purification process.

In 1987 – way before the establishment of its current historic preservation ordinance – the City of Beverly Hills considered the old Waterworks building a safety hazard and approved the site for demolition. It was only when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was willing to "pick up the tab" that government officials stood behind its preservation – and in 1991, it reopened as the Margaret Herrick Library and Fairbanks Center for Motion Picture Study. It’s a non-circulating library, which means its collection stays there – but any member of the public is welcome to come peruse the manuscripts, photos, production art, and more in its physical and digital collections.

5. Bullocks Wilshire Building, Wilshire Center

Built in 1929 and designed by John Parkinson, the flagship Bullocks department store on Wilshire Boulevard was one of the first department stores to cater to car culture – with sidewalk-facing window displays to attract the eyes of Wilshire Boulevard motorists on their way east to downtown or west to the Miracle Mile. The iconic tower, rising 241 feet and topped with tarnished green copper, rose above what was then a relatively residential neighborhood and served as a beacon for more than 60 years. The building sustained significant damage during the 1992 L.A. Riots (then under the ownership and operation of Macy’s) and closed in 1993 – but that didn’t spell doom for the “cathedral of commerce,” because Southwestern Law School purchased it in 1994 and embarked on a $29 million restoration to make it suitable for academic purposes.

The Central Hall is still reminiscent of the lobby of the Empire State Building, but you will no longer find an ostrich feather Christmas tree there during the holidays.

In the first floor East Room – formerly a salon for designer shoes and accessories – original lighting fixtures and ceiling details have been incorporated into the design for the Julian C. Dixon Courtroom and Advocacy Center. The former Women's Sportswear Department is now the Reference Room, whose "The Spirit of Sports" mural is the central focal point. Original 1929 elements intermingle with other design features added later – like a Moroccan chandelier and an inlaid compass in the terrazzo floor of the Palm Court, both from the 1960s. On the second floor, there are a variety of "Period Rooms," where top designer fashions were modeled by "live mannequins." The Louis XVI Room transports its visitors to Marie Antoinette's boudoir in the Palace of Versailles; La Chinoiserie once housed the Chanel Boutique with its French Rococo design with a touch of China, by way of France. Because it now operates full-time as the Southwestern Law School, you can only get into the landmark during a summer open house hosted by Friends of Bullocks Wilshire.