When L.A. Was Empty: Wide-Open SoCal Landscapes

Early photographs of Los Angeles surprise for many reasons, but often what's most striking is how empty the city looks. Open countryside surrounds familiar landmarks. Busy intersections appear as dusty crossroads.

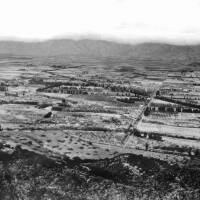

Southern California entered the photographic record at the cusp of a dramatic transformation in the region's landscape. When an anonymous photographer stood atop Fort Moore Hill circa 1862 and took the earliest-known photograph of Los Angeles, he captured a small town – population 4,385 in 1860 – embedded within an open countryside. Vineyards, orchards, and other intensive agricultural enterprises occupy the land immediately surrounding the city. Obscured in the hazy distance, meanwhile, were sprawling cattle and sheep ranches, legacies of the region's Spanish and Mexican eras. In 1862, Los Angeles represented one of the few urbanized areas, as modest as it was, in the entire region.

In the 1920s, Los Angeles County ranked first in the nation in the value of its agricultural output.

Over time, the growing city spilled into the surrounding landscape. Meanwhile, a devastating drought that began in 1862 and lasted through 1864 crippled the ranching economy, and more intensive agriculture retreated into the former grazing lands. Pastures became bean fields and orange groves – a process that only accelerated with the arrival of new technologies like groundwater pumping, concrete pipes, and refrigerated train cars. Cooperative enterprises like the Anaheim Colony in present-day Orange County provided a model for making irrigated agriculture work. Providing a variety of microclimates and soil types, the Los Angeles Basin and its adjacent valleys became home to a diverse suite of agricultural uses. By the 1920s, Los Angeles County ranked first in the nation in the value of its agricultural output.

Los Angeles kept growing. It did so in part by expanding outward from its historic core, rolling west toward the sea, but it also sprouted offshoots. First along the steam railroads, then the interurban lines of the Pacific Electric and finally the freeways, suburbs sprang up amid the countryside. Many of the most dramatic photos of an emptier Los Angeles show new settlements like Hollywood or Beverly Hills – now familiar to much of the world through popular culture – as rustic country towns. Eventually, the surrounding countryside disappeared as the suburbs and city merged into one metropolitan agglomeration.

The process reached a fevered pitch in the years immediately following World War II. From 1945 through 1957, subdividers carved 462,593 separate lots out of agricultural land in Los Angeles County. By the end of those thirteen years, nearly all of the San Fernando Valley had become urbanized, and the master-planned city of Lakewood had risen from the bean fields north of Long Beach – an event D. J. Waldie chronicled in his classic memoir "Holy Land."

Some communities resisted. Between 1955 and 1956, for example, three along the zig-zagged border between Los Angeles and Orange counties incorporated to fight encroaching urbanization: Dairy Valley (now Cerritos), Dairy City (now Cypress), and Dairyland (now La Palma). Within a decade, however, even those proud cow towns had adopted new names as real estate developers made dairy owners irresistible offers.

These photographs may inspire nostalgia for a lost, Arcadian past. But they may also provoke pertinent questions about Southern California's urban development and city dwellers' relationship with the natural environment.

Among some viewers, these photographs showing vast swaths of emptiness where urbanization reigns today may inspire nostalgia for a lost, Arcadian past. But they also provoke pertinent questions about Southern California's urban development and city dwellers' relationship with the natural environment. Does the open countryside pictured here, for example, represent a lost opportunity to create a comprehensive system of parks and open spaces? Have Southern Californians become less informed about food production since agricultural enterprises moved to far-off places? And how did the loss of open spaces change popular conceptions of nature, wilderness, and conservation? The urgency of these questions speaks to the enduring value of photographic archives.

Rural San Fernando Valley

Hollywood as a Country Town

Undeveloped Beverly Hills

Western Avenue at the Turn of the 20th Century

Around Town