When L.A. Was a City of Vines: Q&A With 'Tangled Vines' Author Frances Dinkelspiel

Click here to read an excerpt from author Frances Dinkelspiel's book "Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California," where she reveals surprising connections between L.A. and California's modern wine trade, tracing the industry's fraught history.

Long before Napa or Sonoma became household names across the globe, the City of Angels reigned as the viticulture capital of California.

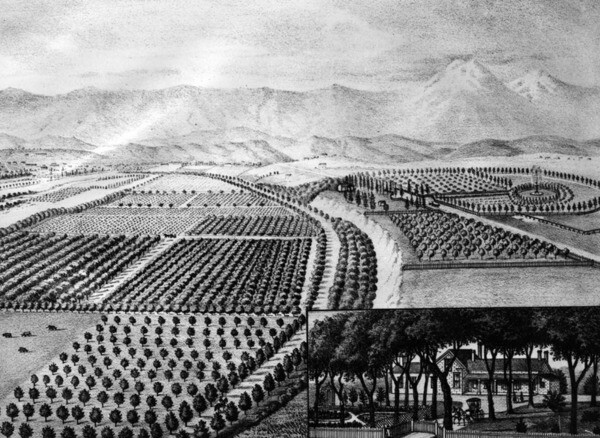

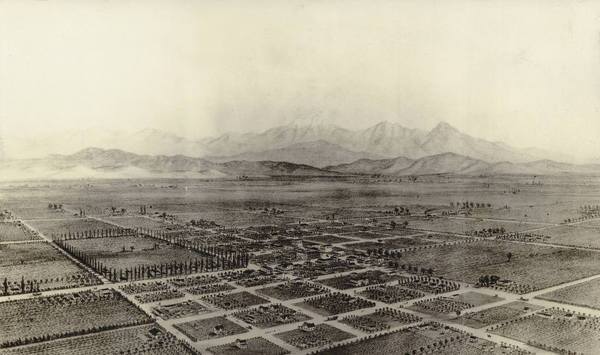

In 1850, the angels numbered only 1,610, but the city's 100-or-so vineyards along the rich floodplains of the Los Angeles River produced 57,355 gallons of wine. Four years later, when Los Angeles adopted its first city seal, it placed within its center a cluster of grapes.

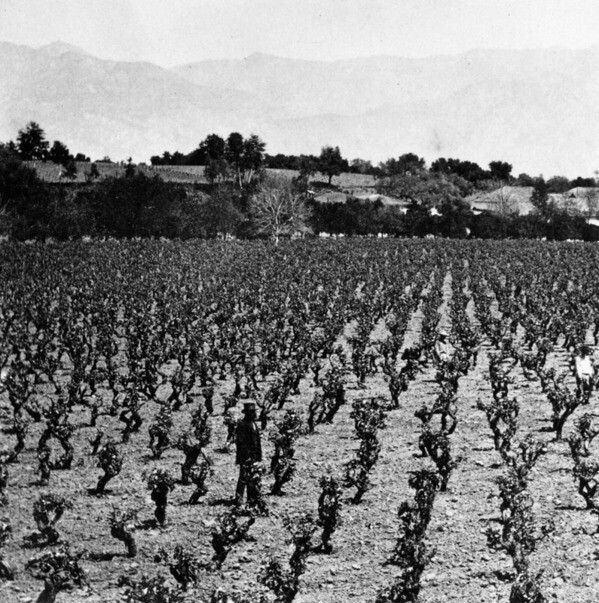

Soon, all across Southern California, vineyards of Mission grapes -- the same varietal planted by Spanish missionaries -- sprawled under the region's sunny skies.

In 1857, German colonists founded a utopian winemaking commune 26 miles southeast of Los Angeles, irrigating their vines with water from the nearby Santa Ana River. They honored the river's contribution in their commune's name: Anaheim.

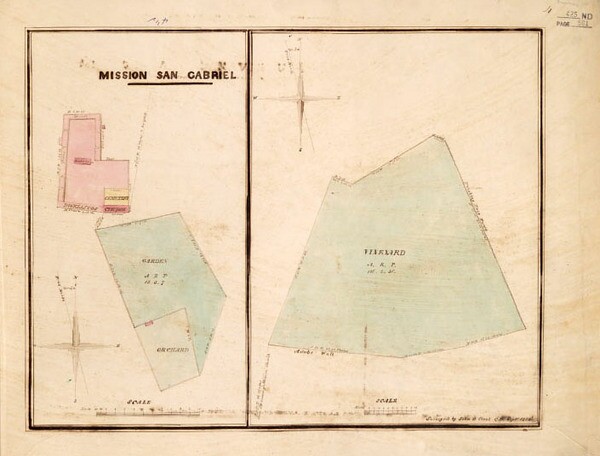

Around the same time, 37 miles east of Los Angeles, the Rancho de Cucamonga emerged as a leading winemaking enterprise.

Cucamonga's lucrative vineyards -- and the jealousies, conspiracies, and violence they inspired -- figure prominently in "Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California," a new book by Frances Dinkelspiel that's at once a gripping tale and an impressively researched work of history.

Dinkelspiel previously chronicled early Los Angeles in "Towers of Gold," her biography of banker Isaias Hellman. Now, in "Tangled Vines," she reveals surprising connections between frontier Los Angeles and California's modern wine trade, tracing the industry's history to its origins in conquest, colonialism, and exploitation.

We recently discussed her book and the research that made it possible. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Nathan Masters: Your book introduces readers to two starkly different worlds. There's the rough-and-tumble world of L.A. in the mid-19th century, and then there's the more privileged world of Northern California's wine country in the 21st century. Injustice is at the forefront of both, but in the earlier time it takes the form of murder, slavery, and racially motivated violence, while in the more recent world it's an arson fire and the loss of some amazing wine collections. Things seem to have improved, but in what ways are the vines of those two worlds entangled?

Frances Dinkelspiel: While things are better now, the history of the wine business in California is in part a story of injustice and exploitation -- one that's not widely recognized or acknowledged by wine makers and trade organizations.

First the Indians were exploited to make wine, then Chinese workers were brought in, and the labor force eventually evolved to include mostly Mexican and Central American workers. And their lives are hard. Things may be much better now, but there are still inequalities.

NM: Your book brought to life a period of Los Angeles history we don't usually experience through fiction or narrative nonfiction. The research must have been extensive. Which collections did you find most useful?

FD: I spent a lot of time going through the rich collections at the Huntington Library, where I reviewed the records of court cases from early Los Angeles and read through letters from various people in the book.

At the Seaver Center, I looked through pictures of early Los Angeles. When you do historical research, you can spend an entire day in an archive, find one good image, and consider it a good day.

I also spent a lot of time in the San Bernardino County Historical Archives. They've done a good job preserving their history. They've got these assessment books -- big leather ledgers -- that tell you how much property or money someone had. And they had a lot of court cases.

Finally, there were these scrapbooks from Benjamin Hayes, who served as a judge in Los Angeles just after California became part of the U.S. He came from the east coast, was well-educated, and recognized the historic nature of California's transfer from Mexico to the U.S. So he kept everything and organized them into scrapbooks, which are now at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley. There's a separate scrapbook about the Cucamonga killing, which figures prominently in the book. Reading through the scrapbook, you feel like you're there. It was amazing.

NM: Broadly speaking, we can characterize regional history in the U.S. by saying that Southern history is about slavery, and Western history is about conquest. But in California -- and especially in the Los Angeles area -- slavery and conquest were intertwined. How does that relationship play out in your book?

FD: Well, it's very interesting that the original labor force that planted the grapes and made the wine were Native Americans. They were essentially indentured servants or slaves from the time Franciscan fathers established the first mission.

And then later, Americans treated the Indians even worse than the Franciscan fathers. One of the first laws they passed after California became an American state was the Indian Indentured Act [officially, an Act for the Government and Protection of Indians], which allowed any vineyardist to declare an Indian lazy. The sheriff could arrest them, fine them. And then when they couldn't pay the fine, the sheriff would auction the Indian workers off to the highest bidder. One early California writer compared that process to the slave marts of the South.

NM: And then there's California's other conquest -- that of the Mexican people by the United States. That conquest is still relevant today, of course, but in 1850s Los Angeles the wounds of the war were especially fresh. Bill Deverell even termed that time period as the "Unending Mexican War." How would you describe the racial climate of the time?

FD: It was terrible, with widespread distrust between the native Californians and the white Yankees or Europeans. There were lynchings. There was a lot of unfair frontier justice. It was a violent time.

A fantastic representation of that climate took place in 1862, during the Civil War. A man named John Rains, who owned a famous vineyard in Rancho Cucamonga, was murdered when he was traveling between his home and Los Angeles. His body wasn't discovered for 11 days. And during that time people were whispering that it was Californios who killed him.

One of the men suspected in the murder was being transported up to San Quentin for a different offense. As the sheriff was loading him onto a boat in San Pedro, a vigilante mob came aboard. They grabbed the man from the sheriff, hung him right there on the boat, filled his pockets with rocks, and threw him overboard. Another California suspected in Rains death was later gunned down, as well.

Life was cheap, particularly if you were a Californio, or a Mexican.

NM: Viticulture was once a major industry in Southern California. Can you explain why that isn't so today? And how did the north ever overtake the south as the center of winemaking in California?

FD: There are a couple different reasons. Probably the most significant is that Southern California isn't really well-suited for winemaking, especially because it's much hotter than in northern California.

Early planters used the Mission grape, which was the most commonly planted grape in California until 1890. The Mission grape is a very hardy grape that thrived in the hot sun of Southern California. But the wine made from it wasn't really good.

Eventually, more people came to California, including people from France and other countries with strong winemaking traditions. They sought out other grape varietals to experiment with and, while some were planted in Southern California, they didn't do as well as in Northern California, where nights are cool. It's really important to let wine grapes cool off at night.

And then there was something called Pierce's disease, which rushed through all the vineyards in Southern California, and killed off them all off in a period of two-to-three years in the late 1880s. At the same time, there was a population and real estate boom. Here all these vines had died, and this sudden influx of people found other things to do with the land.

And yet Southern California was the heart of California's industry for a really long time, and from 1860 to about 1890 it was the heart of winemaking in the U.S., as well. There were so many grapevines that Los Angeles was called "The City of Vines."