Vast Swaths of Southern California Once Belonged to Pío Pico

Vast swaths of Los Angeles and Orange counties once belonged to Pío Pico.

Pico, the last governor of Mexican Alta California, once owned half the San Fernando Valley in the form of Rancho Ex-Mission de San Fernando. Present-day Camp Pendleton also belonged to him when it was Rancho Santa Margarita. The communities of Anaheim, Buena Park, La Habra and Cerritos were his, too, as Rancho Los Coyotes, as were Montebello, Whittier and Pico Rivera when they were Rancho Paso de Bartolo.

Though he inherited nothing, Pico quickly realized that power and influence came from land ownership.

Unlike many of his Californio neighbors, Pico was a self-made man. “Nothing was left us – even an inch of ground,” he wrote in his autobiography, recalling his father’s death. Yet he quickly realized that power and influence came from land ownership. Through his political connections, Pico secured Rancho Jamul in 1829, his first large piece of land, and one situated relatively close to the San Diego Mission where he was raised. Located 20-30 miles inland, the land was prone to attacks by inland Indian nations that had evaded Spanish colonization and Christianization. When Pico was jailed in 1837 for leading a rebellion against Gov. Juan Bautista Alvarado, these Indians attacked his Rancho Jamul and killed his workers while his mother and sisters were able to escape to safety. Pico sold the land in 1851 but had to file an ownership claim with the Board of Land Commissioners, which was rejected in 1855. The new owners then spent decades in litigation over the land that has since become Rancho Jamul Ecological Reserve.

[view:kl_discussion_promote==]

Granted in 1841, Pico’s largest parcel was Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores, which “had seven rivers and creeks, seven lakes, thirty-five miles of coast, two mountain ranges and vast grazing lands,” according to his biographer Carlos Manuel Salomon. Pico loved this profitable rancho, but problems arose in 1862 when he had to cover the debts of his brother Andres. In need of financial relief, Pico sought the help of his brother-in-law Juan Forster. Instead of drafting loan documents, Forster gave Pico a deed of sale knowing this brother-in-law couldn’t read English. Trusting his brother-in-law, Pico signed the documents without first consulting his lawyers. A well-documented court case ensued; Pico lost the property. While evidence suggests that the brothers’ befuddled testimony worked against them, Pico was a victim of “a gross miscarriage of justice” in the judgment of Paul Bryan Gray, author of “Forster vs. Pico: The Struggle for Rancho Santa Margarita.” The land passed through several owners before the U.S. Marine Corps bought it in 1942 to build Camp Pendleton.

While Pico was land rich, many of his real estate holdings were entangled in a myriad of lengthy court cases. Pico, along with his brother and another partner, endured a five-year trial to obtain legal ownership of Rancho Los Coyotes, part of the larger original grant given to Manuel Nieto. Pico lost the property to Abel Stearns when he couldn’t repay the interest on Stearns’ loan.

Adding another knot to the tangle of land issues was Andres Pico’s excessive gambling. Pico’s younger brother was habitually placing risky bets that caused constant financial strain. In 1853, Andres Pico bought half the land that was formerly Mission San Fernando, which he then put up as collateral for a loan to pay off his debts. Andres later transferred the land to Pío in 1862 to avoid foreclosure. Pío eventually returned a part of the land to his brother and sold the other portion to Isaac Lankershim in 1869 to raise capital for construction of his Pico House hotel in Los Angeles.

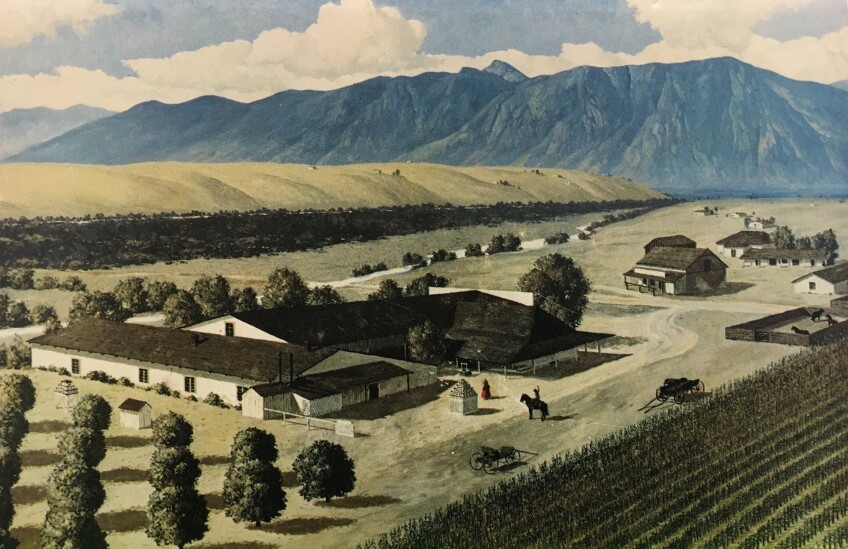

Pio Pico State Historic Park in Whittier sits on the former site of Rancho Paso de Bartolo, a parcel granted in 1835 to Juan Crispin Perez. When the property was divided among Perez’s children after his death, Pico bought the individual parcels from each heir between 1849 and 1852. Once he secured all the land rights to what he affectionately named El Ranchito, Pico built a 20-room adobe mansion that became his family’s permanent residence, as it was close enough to the pueblo to conduct business but distant enough to serve as a restful retreat. The neighboring San Gabriel River created fertile conditions for orchards, so he rented part of his land to tenants, which proved very lucrative.

The court case over El Ranchito would be Pico’s last, longest and perhaps most heartbreaking. The case involved false testimony against Pico along with another fraudulent contract that Pico thought was a loan document but instead was a deed of sale. While the evidence favored Pico, his lawyers could not argue against Pico’s signature on the deed. Pico vs. Cohn lasted so long that Cohn died before the case’s resolution. After four appeals, the case was settled in 1891 and Pico had to leave his cherished Ranchito at the age of 91. The city of Whittier bought the land in 1905 for the water wells on the property, but it was Pico’s friend Harriet Russell Strong, a successful businesswoman, who led efforts to preserve the adobe mansion. She had the property deeded to the state of California and by 1927, Pío Pico’s El Ranchito became one of California’s earliest state historic parks.

Of all the Southern California municipalities that occupy Pico’s former landholdings, only one bears his name: Pico Rivera.

Selfish profiteers conspired against the aging Californio, but Pico was not a passive victim. He fought back vigorously, turning to the American judicial system so often to settle his disputes that his biographer dubbed him the "the most litigious Californio ever.” Pico believed that one had to take enormous risks in order to succeed. Even in his old age, his ambition and competitive nature continued to drive reckless decision-making, which is why his rags to riches to rags story is so engaging. “Desire for land drove the young Pico to enter politics and business, wrote Salomon. “For anyone born without inheritance, however, becoming an influential citizen proved nearly impossible, making Pico’s success extraordinary.”

Of all the Southern California municipalities that occupy Pico’s former landholdings, only one bears his name. The City of Pico Rivera began as two separate townsites; Rivera took shape in 1887 when the Santa Fe Railway came through the area, and when the village of Pico formally adopted the name of the area’s former landowner 30 years later. In 1958, to avoid annexation from nearby municipalities, the two towns merged and incorporated as one city – thus enshrining Pico’s name on maps of Southern California.

The author wishes to thank the Pico Rivera History and Heritage Society and the Pio Pico State Historic Park for providing research materials for this article.

Further Reading

Carlos Manuel Saloman, Pio Pico: The Last Governor of Mexican California (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

Paul Bryan Gray, Forster Vs. Pico: The Struggle for the Rancho Santa Margarita (Spokane: The Arthur Clark Co., 1998).

Martin Cole, Pico Rivera: Where the World Began (Whittier: Rio Hondo College Community Services, 1981).

Robert Glass Cleland, The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California 1850-1880 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1951).