They Built This City: How Labor Exploitation Built L.A.'s Attractions

The Ye Alpine Tavern and resort, built by Professor Thaddeus Lowe at the peak of the Mt. Lowe incline railway, is celebrated as a relic of Los Angeles' recreational heyday. In the early 1900s, millions of tourists came to Los Angeles to enjoy the natural attractions and overnight accommodations at Mt. Lowe. However, Mt. Lowe's past is one of labor exploitation and disease as much as recreation and health. After assuming ownership of the Mt. Lowe railway and tavern in 1906, Henry Huntington and his Pacific Electric Railway Company built labor camps to support the planned renovation. While Huntington's leisure resorts were praised for their contributions to health and connection to nature, his labor camps — and their predominantly Mexican inhabitants — were associated with disease. In these disparate developments, connections were forged between health, housing and the service industry that continue to disproportionately affect Los Angeles' Latino/a/x populations today.

The temperate climate of Southern California and the bungalows designed to reap the benefits of it were primary attractors for tourists hoping to escape crowded, industrial cities around the turn of the century. Mt. Lowe supported this vision, with its lushly landscaped hills and views of the San Gabriel Valley. But as of 1900, demand for the railway and resort had steadily declined. Henry Huntington, the region's primary developer of rail, water and power infrastructure, saw potential in the site. Under the direction of his Pacific Electric Railway Company (PERC), Huntington acquired the then stagnant railway and resort and began its decades-long renovation. Infrastructure underpinned the reinvention of Mt. Lowe as a modern, healthful retreat with electrified cottages, gas kitchens and privatized baths.

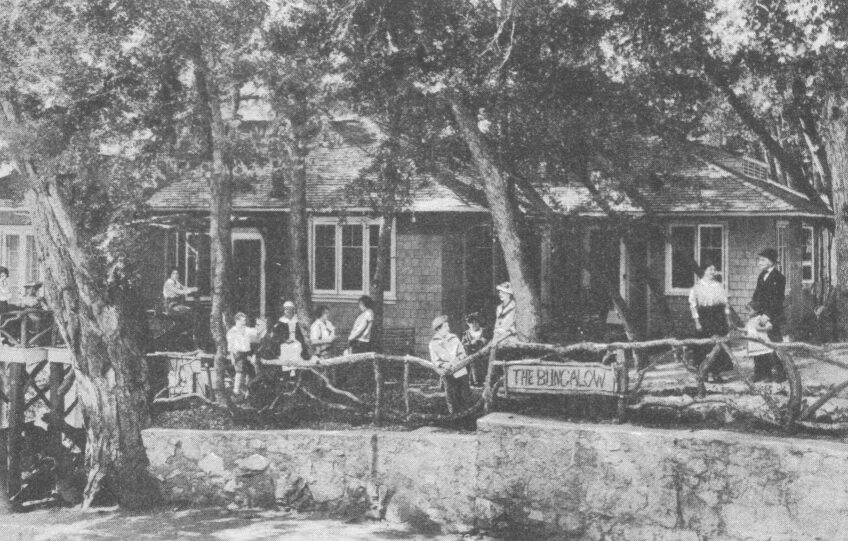

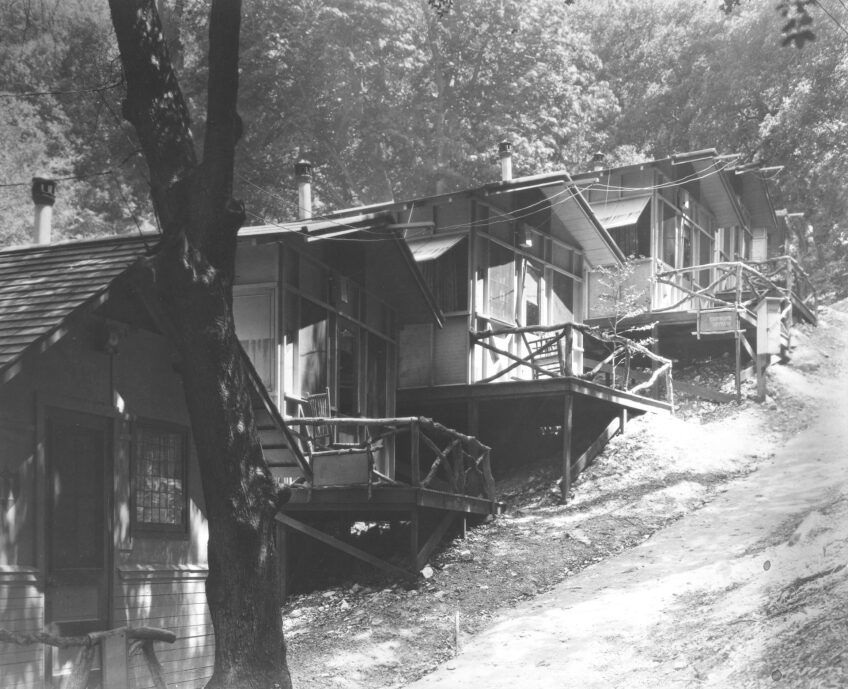

Myron Hunt, prized architect of the Huntington Hotel and several Pasadena mansions, was hired to design the renovations. Hunt specialized in bungalow and cottage design using lightweight materials inspired by nature to construct accommodations in connection with their environment. The new Hotel Bungalow and tent cottages were designed with private piazzas and large screened openings. Cottage guests were encouraged to sleep outside on their private porches to reap the benefits of the setting, which featured fresh mountain air, scenic vistas and lush forests. George Wharten wrote of the benefits of "Scenic Mount Lowe" in 1908 citing physicians in their belief of the healing power of the mountains. The Mt. Lowe resort was promoted as a cure for communicable diseases like tuberculosis, typhus and the plague, outbreaks of which had grown within the nation's industrial cities.

Though spacious developments like that at Mt. Lowe remained relatively unscathed, densely populated regions experienced increased cases of disease as the county's population grew. The labor camps and laborers behind Huntington's empire were made especially vulnerable. Huntington recruited Mexican immigrants to construct and maintain his infrastructure and resorts, believing them to be low-cost and loyal employees. As an enticement, Huntington's PERC offered free housing to the company's laborers. The communal bunk houses, or "section houses" as they were called, presented dangers to employee health and safety. The laborers who supported Mt. Lowe and the Pasadena tourist economy were housed in camps down the mountain from the tavern and in South Pasadena. A visiting nurse for the Associated Charities described the PERC camp along Glenarm in South Pasadena as an infested, overcrowded and filth-ridden collection of shacks and tents. Over one hundred employees were sharing just twelve rooms. When a sociology student from the University of Southern California surveyed Pasadena in the 1920s, she documented that 57% of Los Angeles' Mexican population were living in this southern section. As concerns of disease amassed, the California Commission of Immigration and Housing (CCIH) drafted regulatory measures for rail labor camps. The PERC camp was flagged for demolition.

Pressed by the CCIH, the PERC rebuilt the camp along Glenarm. The "shacks" were replaced with new dwellings of the same communal form but were presented as increasingly "tidy." In the PERC's promotional article on "How the Company has Aided the Mexican Worker," paving, landscaping and a trash incinerator were foregrounded. Despite the orderly appearance of the new camp, the visible holding tank of the L.A. Gas Company in the background served as a reminder of the adjacent density and industrial use. The PERC enforced "tidiness" by employing what PERC called a "visiting nurse," in line with the CCIH's recommendations. Nurses and teachers were sent to camps and employed by companies to teach Mexican women and girls cleaning and housework and Mexican boys in construction and woodwork. By hiring persons to teach Mexican children in the service and construction industries, employers ensured a low-level workforce for future generations. In the article, Mexican women and children were pictured wearing clean white dresses, lined up in an orderly row on either side of the nurse as a marker of this practice. The nurses did more to maintain appearances, teach discipline and provide vocational training than to improve the health of camp inhabitants.

Camp reform efforts were designed to combat the supposed cultural disposition of Mexican populations, but it was really the employers that dictated the laborers' living conditions. Most ethnically Mexican Angelenos were employed as manual laborers, making it near impossible for them to afford better housing. According to the 1910 Census, the PERC housed Isabella Lopez and her daughter Juana Saucedo, who worked as launderesses in the single-family homes of the neighboring suburbs. Mexican immigrant men in the southern section of the Pasadena camp such as Jacinto Ananze Coronacel, Emilio Arieta and Antonio Canales worked as laborers for the gas company and the railway, and in constructing and maintaining the city's sewers and streets. Huntington selectively hired Mexicans who were willing to abide by his anti-union policies to work in his railway, utility and construction subsidiaries. In 1914, unskilled laborers were paid 20 cents an hour, or $10 per week on average, compared with union workers like those of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, who made 53 cents an hour or $26.50 per week on average. A 600-square-foot home and lot cost $1,600 on average and could be financed for $10 per month at 6% interest. With only $40 per month to spend on their families, non-union construction and service workers would have had an extremely difficult time affording a home. In 1922, of the 984 Mexican inhabitants of the southern section of Pasadena, only eight owned a house or land. The PERC's pairing of low wages with labor camp housing was designed to ensure a propertyless and therefore subservient workforce out of Los Angeles' Mexican population.

Los Angeles' leisure economy, exemplified by the famed Mt. Lowe resort, would not have been possible without laborers like Lopez and Coronacel. Ethnically Mexican immigrants and migrants trained in construction and domestic service and relegated to low-level employment, built the rail and maintained accommodations for leisure-seekers. The railways brought those with expendable wealth and time to Los Angeles, where the temperate climate and outdoor accommodations promised superior mental and physical health. But the health found at Mt. Lowe was supported by the exploitation of Mexican workers.

These historically-forged, systemic inequalities continue to affect Los Angeles' Latino/a/x populations and communities today. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, more than half of Los Angeles' Hispanic population are employed in low-earning occupations. The median weekly earnings of full-time workers from 1979 to 1997 was just over $400 for Hispanic men, compared to $800 for White men. With almost 25% employed in service occupations and the highest rate of severe overcrowding in the county, Latino/a/x populations are more susceptible to poverty and disease. Low-paying jobs which are "essential" to the maintenance of our economy typically require the most interaction with the public. While living in households and working in occupations where social distancing is difficult, Latina/o/x people have been rendered most vulnerable to COVID-19. 46.4% of L.A. County's ethnically Latino/Hispanic population contracted COVID-19 as of April 2020, compared with just 23.7% of the White population according to the Public Health Department. Given the congruences between these contemporary and historical pairings of health, housing and employment, there remains much to learn from the history of the labor camps behind Mt. Lowe.

Sources:

Myron Hunt & Walter Webber, Associate Architects, "Pacific Electric Railway Co. Hotel Cottages Revised into Housekeeping Cottages," Pacific Electric Collection, Southern California Railway Museum Archives, Perris, CA, 1917.

A.C. Lofstedt, "A study of the Mexican population in Pasadena, California" (Electronic Theses and Dissertations) University of Southern California, 1922.

G.J. Wharton. Scenic Mount Lowe and its Wonderful Railway (Los Angeles, CA: Pacific Electric Railway, 1905).