The Sycamores of Southern California: A Brief History

In a land of few trees, the sycamore stood out. Well-known to the native Tongva (Gabrielino) people of the region, the western sycamore (Plantanus racemosa) was one of the few trees to shade the lowlands of coastal Southern California. When the Spanish first encountered them, the trees escaped easy classification. Mistaken for another tree, they became known as alisos, the Castilian word for alders.

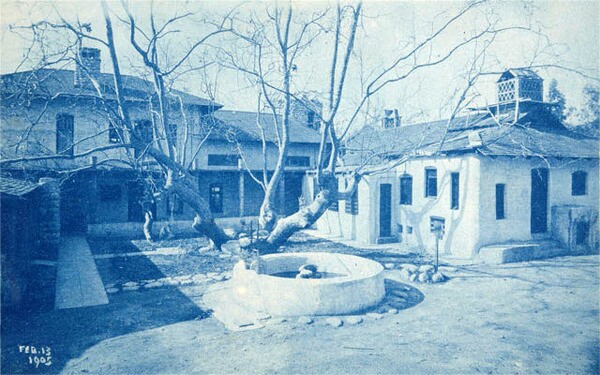

Thirsty plants, sycamores often clung to the banks of streams. The Arroyo Seco, a seasonal watercourse between Pasadena and Los Angeles, is famous for its graceful sycamores. A public campaign led to the 1903 protection of one exceptional stand as Sycamore Grove Park, though most of those trees were destroyed in a 1914 flood and replaced with seedlings. Another campaign to save two nearby trees located in the middle of Avenue 64 failed. Those trees fell to the axe in 1915. Charles Fletcher Lummis, meanwhile, built his streamside, stone-masonry house around an Arroyo Seco sycamore, naming his residence El Alisal.

Though they thrived near streams, sycamores sometimes took root in plains with abundant groundwater. When that happened, they could tower over the landscape. Flaunting their immense age through their mottled trunks and twisted branches, well-placed sycamores became famous landmarks, inspiring romantic tales and standing as tangible connections to the past.

El Aliso was perhaps the grandest of all. Located on the flood plain of the Los Angeles River and near the Tongva village of Yaanga, the tree had already witnessed nearly four centuries of human history when the Spanish founded the Los Angeles pueblo nearby. Tongva leaders reportedly traveled great distances from across the region to confer under the shade of its canopy. A French winemaker placed his cellar under its cool, protective cover. By then, it had grown to massive size, its trunk standing 60 feet tall its branches stretching 200 feet from tip to tip. But urbanization eventually spelled doom for El Aliso. As the winery became a brewery, new buildings crowded the tree's spreading branches, leading to excess pruning. A street -- ironically named Aliso after the tree -- ran over its root system. By 1892, the ancient sycamore had succumbed to the stress of its surroundings.

In Sawtelle, another famous sycamore came to embody the romantic past. According to local lore, Father Junipero Serra once prayed beneath the massive sycamore's bough while on a mission-founding journey through California. Stories also connected the tree -- like many other native oaks and sycamores across the state -- to the violent 1850s, when many Mexican Americans were lynched in a continuation of the Mexican-American War's racial violence. According to one account, 21 men were hanged from the Sawtelle tree. Marred by an arson fire, the tree met its own end in the 1920s.

Other sycamores became notable for their conspicuous profile rather than any historical associations. One became a boundary marker in 1871, when Rancho San Rafael was partitioned into parcels. It delineatde the border between the cities of Glendale and Los Angeles and later guarded the entrance to Glendale's Forest Lawn cemetery. Though scarred by spike holes and other marks left by surveyors, the tree was made a monument in 1930, when the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a plaque at its base.

In present-day Compton, another stately sycamore marked the northern boundary of Rancho San Pedro, drawn on the land grant's diseño. When the American authorities later confirmed the land grant, the sycamore was such an established landmark that it needed little description: "Beginning at a sycamore tree, sixty inches in diameter, standing on the east of the road leading to San Pedro..." began the proclamation.

Named the Eagle Tree after the raptors that reportedly nested in its branches, the lone sycamore stood out in a mostly treeless landscape. It made an impression on a young farmer named J. Wesley Gaines, who arrived in the area in the early 1870s. "I can still remember when that tree was the only one in the entire area," he told the Los Angeles Times in 1954.

Urban development eventually caught up with the sycamore. Plans in 1947 for a new Standard Oil pipeline called for the tree's removal. In response, the Compton Parlor of the Native Daughters of the Golden West led a spirited campaign that moved the pipeline and saved the Eagle Tree. Today, the ancient sycamore still stands at the corner of Short and Poppy Avenues, growing from a Chevron easement and shading the yards of nearby homes.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, cultural institutions, and private collectors. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.