The Problem of Profitable Leisure: Bringing Chautauqua to Los Angeles

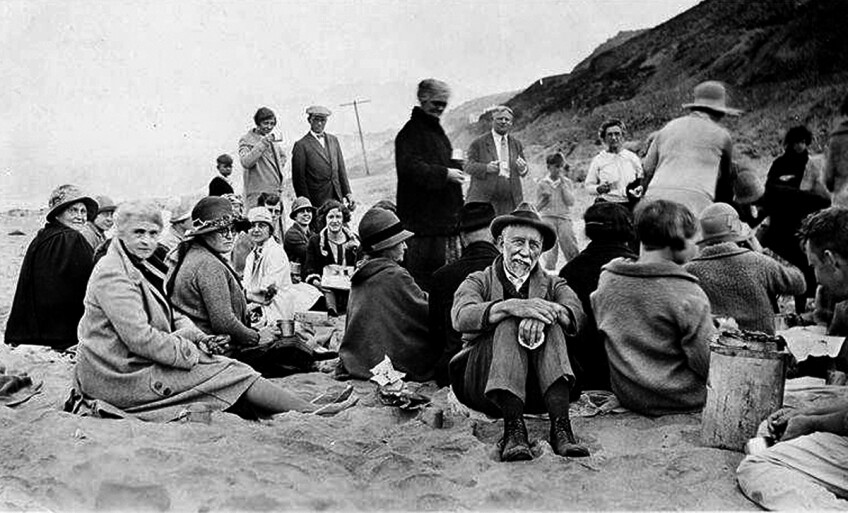

By the thousands, between 1881 and 1940, vacationers who called themselves Chautauquans gathered for a summer week or two at rustic campgrounds in the canyons of Pacific Palisades and along the beaches of Venice, Long Beach, and Redondo Beach. They were drawn there by a national movement of progressive Protestants that idealized learning but also offered entertainment, uplift, and healthy outdoor recreation.

Chautauquans were fiercely proud of their name, which bound them to the “mother Chautauqua” in upstate New York. Their movement was born in 1874 at Chautauqua Lake and began as a summer training program for Methodist Sunday school teachers – origins that reappeared in the campgrounds that “daughter Chautauquas” established in Los Angeles (and elsewhere in California) in the 1880s. An appreciation of nature, some proximity to water, and a spirit of Methodist belief linked the Chautauquan source to the Los Angeles summer camps and to what became dozens of local Chautauqua reading circles.[1]

Chautauqua was many things to its members. It was a home study course that, if followed over four years, gave graduates the breadth of a liberal arts education.[2] It was a weekly meeting of Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle members where readings in the home study course were discussed, guided by instructions and questionnaires in the monthly Chautauquan magazine. And it was an opportunity to spend a few days each summer with other Chautauquans while attending lectures, performances, and discussions in an outdoor setting.

Those who completed the Chautauqua course received an honorary diploma in a ceremony that had the pomp of a college graduation.[3] On Recognition Day, just as the summer assembly closed, the graduate Chautauquans walked through the “Golden Gate” of learning and were presented with their certificate. Chautauqua gave them the liberal education they had never received, since nearly all the graduates were women, small shop owners, or tradesmen whose schooling had ended (at best) in the eighth grade.

The reading course was eclectic. Under the banner “Look Up and Lift Up,” the handbook for the readings in 1890 directed circle members to purchase from the Chautauqua Institution (for a total of $5): “Outline History of England” by James R. Joy, “From Chaucer to Tennyson” by Professor H. A. Beers of Yale, “Our English” by Professor A. S. Hill of Harvard, “Classic French Course in English” by Dr. W. C Wilkinson, “Walks and Talks in the Geological Field” by Professor Alex Winchell, and “Short History of the Church in the United States” by Bishop J. F. Hurst. The handbook urged circle members to read one hour each day, which would be enough to complete all the required texts in a year. “Though you read alone,” the handbook assured Chautauquans, “you belong to a world-wide fraternity.”

“Fraternity” concealed Chautauqua’s overwhelmingly gendered membership. In the 1890s, as the number of Chautauquans in reading circles grew to more than two million nationally, only one-quarter were men.

The Chautauqua movement was earnest and high-minded and – inevitably in Southern California – caught up in real estate speculation, boosting tourism, and the ambition of the Southern Pacific Railroad to build up traffic along the company’s coastal route. (Nearly all the independent Chautauqua assemblies allied themselves with a railroad.) Chautauqua summer camps were opportunities to sell the charms of the landscape, train tickets, hotel stays, and house lots, sometimes on the campground itself or in a new town to be incorporated on Chautauquan principles.

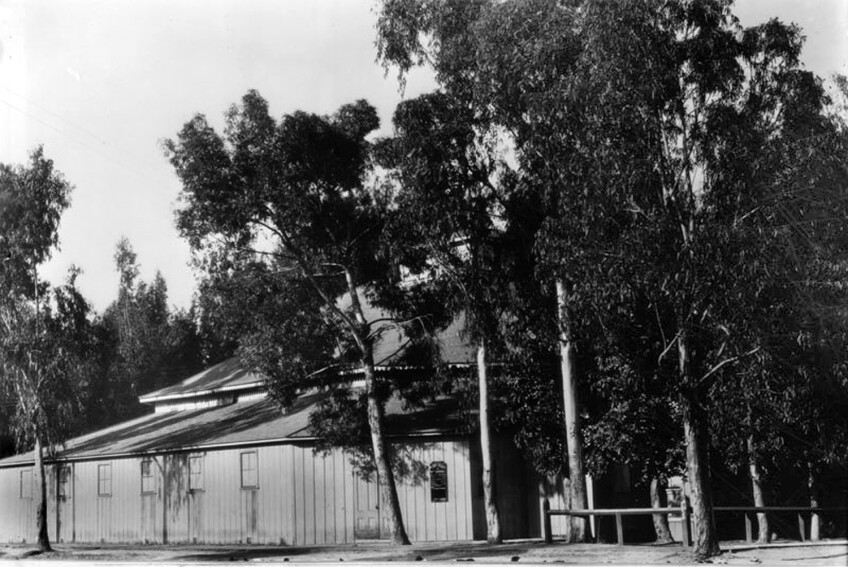

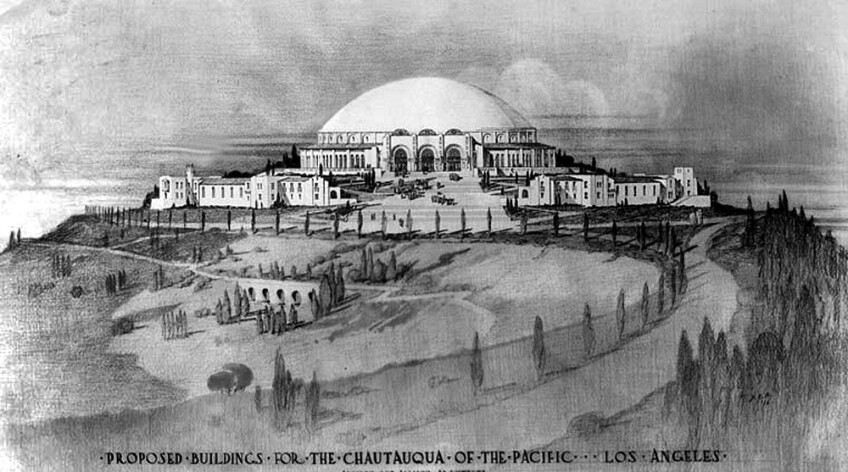

At Long Beach, Redondo Beach, Huntington Beach, Venice, and Pacific Palisades, real estate developers recruited Chautauqua organizers – typically Methodist clergy – with offers of land for a campground, house lots that the assembly might sell to members, and support for the construction of an assembly space – a “tabernacle” – that could seat more than 2,000 attendees. The campground and tabernacle would be located among a grove of trees. And if there was none on the raw land of the speculative subdivision, a grove would be planted to shade the Chautauquans.

At Long Beach and later in Temescal Canyon, as elsewhere, the campground was shared by a Methodist summer school, and Methodist clergy and lay members led and participated in both programs.

The Los Angeles Chautauquas were extraordinarily popular, and anyone could attend the lectures and performances; tickets were only 25 cents. In 1897, the Los Angeles Times reported:[4]

(T)housands of people from all over California and Arizona have gone to Long Beach to live amid cool breezes from off the ocean, and gather instruction in almost every branch of general learning. Last July and August saw the greatest gathering of people at any Chautauqua assembly ever held in California, and there were fully 3,000 more people in camp along the seashore than in any previous season.

Their desire for communion with literature, music, art, nature, and milder forms of non-denominational religion reflected the isolation that newcomers to Southern California often felt. Professor H. B. Norton, writing in 1879 in The Pacific School Journal, lamented:

Thousands of men and women …, especially those living in rural homes, feel discontented with life, on account of the small opportunity for culture, which it has brought to them thus far. They look back at an experience of hard work, incessant longing for more knowledge, for communion with cultured minds, and a wearisome succession of disappointments.

Their desire also reflected concerns about the changing pace of life in a modernizing America. Chautauqua organizers spoke movingly about the toil and strain of industrial labor and the “ceaselessness and monotonous” quality of office work. Attending a summer assembly, said organizers (already deploying the rhetoric of self-help), would make the harried tradesman and bored clerk “brighter and stronger for the tasks of the future” with the “smallest imaginable effort.”

A Chautauquan also would avoid, paradoxically, the other problem of the Industrial Age – too much unproductive leisure. The unoccupied clerk and the tired mill hand were tempted to frequent the saloon and the music hall. Young women spent too much time with sensational novels and theater going. But as U.S. President James Garfield asserted, “The originators of (the Chautauqua) movement have solved the problem of profitable leisure.”[5] By 1904, there were more than 300 Chautauqua summer camps from Vermont to California, giving leisure time a moral purpose.

The Chautauquan goal was “to prepare and protect Christian believers in a modern and changing world.”

The Chautauqua assembly made profitable time for almost any subject that might interest its members. The Long Beach summer camp in 1895 included classes in English literature, art, elocution, music, physical education, botany, biology, astronomy, and Bible study. In 1897, the curriculum added painting and cooking. (There also was a historical tournament and a piano contest.) Lecturers discussed women’s suffrage, prohibition, Darwinism, tariff policy, immigration, penal reform, and international relations. The program, its organizers insisted, was strictly non-evangelical in religion.[6] Still, the Chautauquan goal was “to prepare and protect Christian believers in a modern and changing world.”[7]

Less learning, more entertainment

Chautauquan high-mindedness did not preclude energetic jockeying among competing assemblies in Los Angeles to secure the big crowds that would put a newly platted subdivision on the map. Long Beach lost its Chautauqua to Redondo Beach developers in 1890 in the midst of a lawsuit over who controlled the Long Beach campground and anxieties that Long Beach was about to license its first saloons. A new tabernacle, with seating for an estimated 4,000 attendees, went up on 15 donated acres adjacent to Chautauqua Avenue (now a stretch of Pacific Coast Highway) in Redondo Beach.

The runaway assembly only lasted two years, however. The tabernacle was repurposed as a grain silo and then was purchased by the school district and became part of the city’s new high school.

Chautauqua’s return to Long Beach was only partially successful. By 1909, annual camp programs were being suspended. Programming ten or fifteen days of lectures, classes, field trips, and light entertainment for a thousand or more summer campers had become too much for the assembly’s mostly volunteer organizers. Their place after 1900 was increasingly taken by commercial booking agencies that had organized a “circuit Chautauqua” of tent shows in small towns and rural communities. By 1907, there were at least a hundred of these traveling Chautauquas nationally. Part vaudeville, part revival, and part political debate, they delivered famous orators, science demonstrations, musical interludes, and novelty acts.

Gay MacLaren, a circuit Chautauqua performer, described the variety in her 1938 memoir, “Morally We Roll Along”:

A Chautauqua programme was made up of about two-thirds music and dramatics and one-third lectures. It was served by the greatest aggregation of public performers the world has ever known. There were teachers, preachers, scientists, explorers, travelers, statesmen, and politicians; singers, pianists, violinists, banjoists, xylophonists, harpists, accordionists, and bell-ringers; orchestras, bands, glee clubs, concert companies, quartettes, sextettes, and quintettes; elocutionists, readers, monologists, jugglers, magicians, yodelers, and whistlers.

Although the original Chautauqua Institution continued in western New York after 1920 (and continues still), “Chautauqua” had come to mean any sort of gathering where lectures were interspersed with musical performances, humorous monologues, and non-denominational sermonizing. This was a long way from the Chautauquan source, but extremely popular, selling millions of tickets nationally.[8] After 1920, however, traveling Chautauquas had to complete with expanding educational opportunities, automobiles, motion pictures and radio, and the greater diversity of audience members.

After 1920 traveling Chautauquas had to complete with expanding educational opportunities, automobiles, motion pictures and radio, and the greater diversity of audience members.

The old-time camp Chautauqua – with its brand of ecumenical Christianity – was forced into competition in Southern California with the fiery revivals of Pentecostal churches and the theatricality of fundamentalist preachers like Aimee Semple McPherson. Chautauqua’s embrace of the Social Gospel and its communitarian and reformist goals could not compete.

The Chautauqua movement ended in Southern California in Temescal Canyon on the slopes of Pacific Palisades. The ending was like the movement’s beginning on the shore of Chautauqua Lake, in a grove of trees, by water, shaped by Methodist social concerns, and a real estate development scheme.

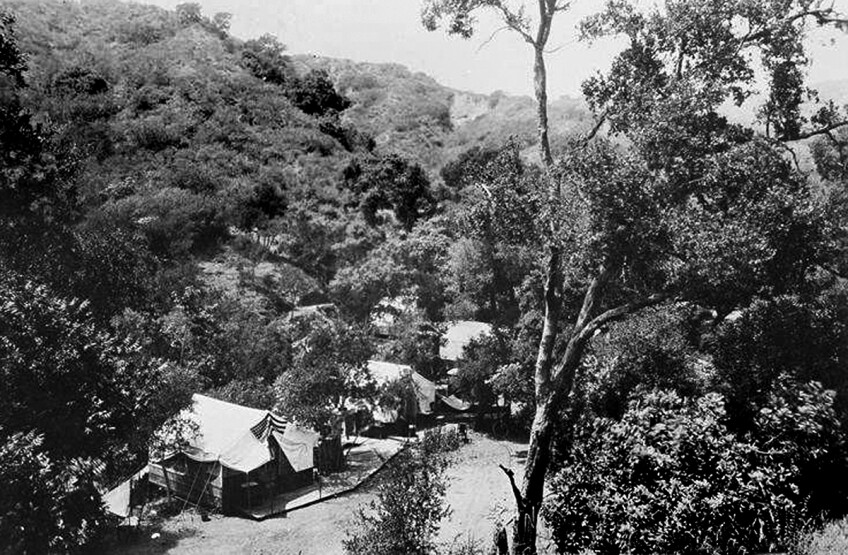

Dr. Charles Holmes Scott was tasked to revive Chautauqua in Los Angeles and build a new and better suburb along with it. Encouraged by the Southern California Methodist Episcopal (ME) Conference, he planned a model community on the 1,100 level acres the ME Conference bought in 1921. Scott’s new Pacific Palisades would embody Chautauquan values of temperance and outdoor recreation. The new subdivision was advertised in 1922 as “The World’s Greatest Christian Residential Community and Education Center.”[9] Above the town, a campground for Methodist and Chautauqua assemblies welcomed summer visitors and potential homeowners.

Scott and his sponsors had purchased the lower end of Temescal Canyon and put up an auditorium, a cafeteria, and a grocery store for campers, along with 35 small cottages and 200 framed tents for summer rental. A tent for two cost $6 for seven days. The Pacific Palisades Association soberly advertised their campground as a “jazz free environment.”

The first Chautauqua summer program began on July 11, 1922. It included a performance by the noted opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink, a lecture by USC president Rufus von KleinSmid, and a dedicatory address by California Governor William Stephens. Shakespeare, the Bolshevik threat, physical culture, art appreciation, and all the other materials of a traditional Chautauqua program were offered during the six weeks of camp.

The Chautauqua in Temescal Canyon lingered until 1934 and faded as the Depression worsened. The campground was sold for use as a private retreat center and resold in 1994 to the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. The conservancy’s Temescal Outdoor Education Program carries on the Chautauquan spirit of learning in and from nature. Some of the Chautauquan buildings still remain at the conference center in Temescal Gateway Park, including the cafeteria.

Chautauquan legacies

There are other reminders of Chautauqua in the Los Angeles landscape. Street names and a park in Redondo Beach remember that city’s brief role in selling house lots and the Chautauquan experience to summer visitors. Chautauqua Boulevard in Pacific Palisades remembers the campground in Temescal Canyon.

The true Chautauquan legacy in California is elsewhere, however.

Chautauqua as the earnest expression of turn-of-the-century Protestant clergy and laymen, mostly but not exclusively Methodist, was gone but the Chautauquan idea had long been a part of the state’s social and political infrastructure. The reading circles of the 1890s had become the state’s reform-minded and politically active women’s clubs, many of which continue today. The Chautauquan emphasis on moral regeneration through nature had already blended with the national park movement, and Chautauquans (among them John Muir) had joined in founding the Sierra Club in 1892. Chautauquans had debated women’s suffrage and helped make California a “votes for women” state in 1911.

With their origin in Silicon Valley and their early venues in Monterey and Long Beach, the first TED conferences aptly combined Chautauquan breadth with a Californian focus on innovation.

The Chautauquan ideal of lifelong learning also passed into the college extension movement and adult education programs. Today, lively, illustrated presentations explore themes in literature, science, philosophy, and history in the very Chautauqua-like TED conferences. With their origin in Silicon Valley and their early venues in Monterey and Long Beach, the first TED conferences aptly combined Chautauquan breadth with a Californian focus on innovation.

Even Chautauquan leaders at the time worried if the crowds thronging the campground groves were too smug, too comfortable in their assumption of privilege.

Some of the criticism of today’s TED conferences mirrors the doubts that 19th-century critics had about the value of the Chautauquan experience, that it was too easy, popular, and unsubstantial. The substance of the Chautauquan audience in Southern California – white, Protestant, lower-middle class – was doubted too. Even Chautauquan leaders at the time worried if the crowds thronging the campground groves were too smug, too comfortable in their assumption of privilege.

Although the Chautauquan experience in Southern California – constrained by ethnicity, class, gender, and a measure of religious bias – has faded, something of its spirit lives on. You’ll find it in the Californian belief in self-renewal, the regenerative power of nature, and the future.

Notes

[1] Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circles gave additional structure to the home study course. By 1887, there were at least 67 circles throughout the state, including circles in Long Beach, Downey, Pasadena, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Santa Ana, and Huntington Beach. “Chautauqua: The Nature Study Movement in Pacific Grove” by Don Kohrs describes the organization of the Chautauqua circles in the 1890s.

[2] Circle members used readers published by the Chautauqua Institution in New York (supplemented by the Chautauquan magazine) and completed questionnaires that charted their progress in understanding the material. For those who had completed the four-year course of readings, the Chautauqua Institution offered additional correspondence courses.

[3] The Chautauqua Institution oversaw the home study course and its materials, published the monthly (later weekly) Chautauquan magazine, corresponded with the regional assemblies, enrolled new members, and managed the annual summer camp at Chautauqua Lake. The organization of regional assemblies and summer camps, like the reading circles, remained independent of the Chautauqua Institution.

[4] “Long Beach.” Los Angeles Times, 1 Jan. 1897, p. 3.

[5] S. H. Weller. “Southern California Chautauqua Assembly.” Land of Sunshine, July, 1896, p. 78.

[6] The Methodist founders of the Chautauqua movement included religion in every course of study and in the routine of the summer camp day. Intended to be non-evangelical and, within a Protestant context, non-sectarian, Chautauqua assemblies also made room for the study of Islam and Eastern religions. A Jewish Chautauqua assembly was organized by the Reform movement in 1883 and persisted, in a somewhat different form, until 2015. But only a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands of circle members (.6 percent between 1882 and 1891) identified themselves as Catholic. Chautauqua was fundamentally a reflection of progressive Protestantism.

[7] Jennifer Shore, “Bryant Day celebrations chime in the new reading season.” The Chautauquan Daily, August 18, 2012, np.

[8] According to Kohrs, “(E)ach performer or group appeared on a particular day of the program. ‘First day’ talent would move on to other Chautauquas, followed by the ‘second day’ performers, and so on, throughout the touring season. By the mid-1920s, when circuit Chautauquas were at their peak, they appeared in over 10,000 communities.”

[9] Scott planned to lease house lots (and regulate who might live there and what their morals might be). That was changed to outright sale in 1924.