The Oak Trees of Southern California: A Brief History

Comprised largely of non-native trees like the ficus, magnolia, eucalyptus, and the iconic palm, Greater L.A.'s urban forests are in a sense as artificial as the roads and structures they shade. But scattered among these horticultural tourists are some species that grew in Southern California before the first human set foot here: the sycamore, the California bay laurel, the walnut, the oak. Of these, the oak tree especially has been a powerful force in shaping the region's human history.

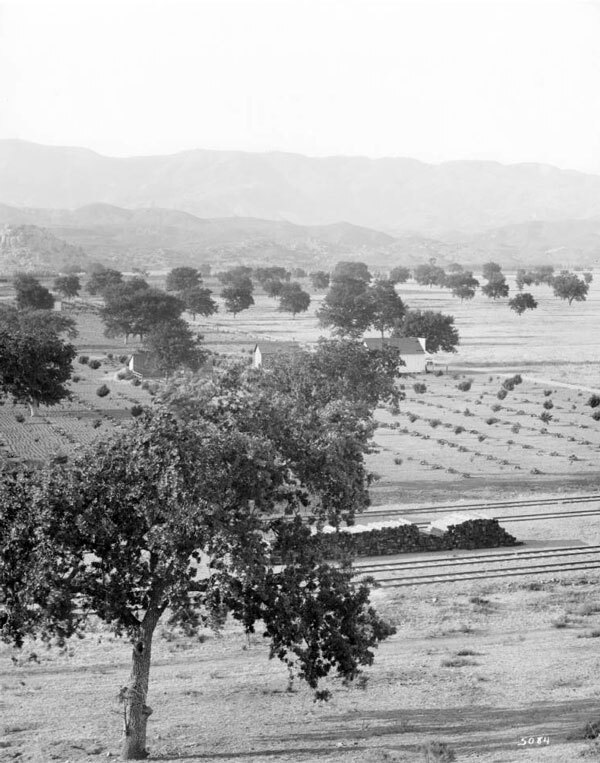

Though still abundant in protected landscapes today, oak trees historically thrived across a much wider range within California. Near Los Angeles, several species -- each adapted to different growing conditions -- graced hillsides, forested mountain slopes, and grew on the savannas of the inland San Fernando, San Gabriel, and Santa Clarita valleys. The coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), interior live oak (Q. wislizeni), canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis), and Engelmann or Pasadena oak (Q. engelmannii), were evergreen, retaining their leaves year-round. The valley oak (Q. lobata), meanwhile, was deciduous. Monarch of the region's oaks, it often produced the largest individuals, which each autumn clothed valley floors in fall color.

The abundance of oak trees allowed California's indigenous inhabitants to achieve one of the highest population densities in the Americas, north of Mexico. Oakwood became an integral part of many communities' material cultures, and, more importantly, acorns gathered from oak trees were a staple of most native Californian diets. Southern California's native Gabrielino (Tongva) people ate acorns -- high in nutritional value, though difficult to prepare as an edible food -- by pounding them in stone mortars, leaching the resulting powder of its tannins, and then eating the wet acorn meal as a cold mush. Oaks and the acorns they provided were so essential to life that several indigenous communities placed them at the center of their creation myths.

When Europeans arrived, they noticed the beauty of the oaks and used them as a way to make sense of their novel surroundings. Upon summiting the Sepulveda Pass and looking out over the San Fernando Valley in 1770, a Spanish expedition called the expansive plain Valle de Santa Catalina de Bononia de los Encinos. ("Encino" is Spanish for live oak.) In central California, a later expedition named a oak-shrouded pass El Paso de Robles. ("Robles" referred to the area's valley oaks.) Later, as highly visible landmarks, some trees served as boundary markers between ranchos, appearing on diseños that recorded Spanish- and Mexican-era land grants.

But almost as soon as the Spanish enshrined the oaks in the region's place names, the more intensive uses of they land they introduced began to threaten the trees' survival. Farming, annual husbandry, and the arrival of non-native annual grasses stymied oak reproduction. Mature oaks were cut for lumber or fuel.

American land use practices only intensified the destructive processes. Like their Spanish predecessors, Americans would name their communities and streets after the trees (Thousand Oaks, Fair Oaks Boulevard, etc.) and then proceed to hasten their downfall. Because of the irregular shape of their trunks, oak trees were rarely felled for lumber, but oakwood came to be prized as fuel. The dense wood and lack of resin meant that the wood and resulting coals burned long and slowly.

Just as they had sustained Southern California's indigenous peoples, oak trees nourished residents of the booming city of Los Angeles, albeit in an indirect and unsustainable way. Demand in Los Angeles for hardwood drew loggers into the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and San Gabriel valleys. As the loggers clear-cut thousands of acres of oak woodlands and savannas and delivered the firewood to Los Angeles, bakers tossed the wood into their ovens, feeding a city while denuding the countryside.

Oaks also fell to the axe as Southern Californians envisioned more profitable uses for oak-dominated landscapes. In the nineteenth century, citrus growers cleared oaks savannas to make way for orchards. Other oak habitats declined as groundwater pumping lowered the water table. Later, real-estate developers uprooted trees to build new houses and commercial properties for the expanding metropolis.

Eventually, as the population of native oaks dwindled, Southern Californians began to appreciate them for more than their consumptive value. Recognizing them as the last-standing sentinels of a lost landscape, some invested the trees with great cultural capital.

Some, it was discovered, were several hundred years old. The massive Lang Oak, with a canopy that rose 75 feet in the air and stretched 150 feet wide, had stood in Encino for more than 1,000 years. When local residents learned that a developer planned to chop it down to make way for a new street, they formed the Save the Oaks Association and rallied for its protection. In 1963, after a six-year campaign, the city designated the oak as Historic Monument No. 24, and the new street curved around the ancient oak.

Other outstanding oaks, remembered or imagined as witnesses to the region's history, gained devoted advocates. In Glendale, the Oak of Peace marked the spot where Andres Pico mulled over John C. Fremont's terms of surrender during the Mexican-American War. The Oak of the Golden Dream in Placerita Canyon marked the site of California's first gold discovery by Francisco Lopez in 1842 -- six years before James Marshall found the precious metal at Sutter's Mill. South Pasadena's Cathedral Oak bore the mark of a cross -- carved in 1770, according to local lore, by Gaspar de Portola to mark the site of the first Easter services in California. And in Calabasas, another local legend entangled the sprawling limbs of the Hangman's Tree with the region's violent past of lynchings and frontier justice. That tree fell to chainsaws in 1965 so that part of a Saturn V rocket, bound for a test site in the Santa Susana Mountains, could pass by on Calabasas Road.

Today, many local jurisdictions protect oak trees by law, requiring permits for their removal and punishing violations as a misdemeanor. In some cases, the destruction of designated heritage oaks is banned altogether.

Yet many of the region's most treasured oak trees have succumbed to sickness, brought on by overwatering and other effects of surrounding development. In 1942, South Pasadena's Cathedral Oak fell to disease. Even Encino's ancient Lang Oak, which had endured countless storms, earthquakes, and other tribulations since it sprouted from the ground in the tenth century, could not survive long amid suburban development. Already weakened by a bacterial infection, it fell on the night of February 7, 1998, as torrential El Nino rains softened the ground around its massive trunk. The next day, local residents gathered around the fallen giant to mourn.

Many of the archives who contributed the above images are members of L.A. as Subject, an association of more than 230 libraries, museums, official archives, cultural institutions, and private collectors. Hosted by the USC Libraries, L.A. as Subject is dedicated to preserving and telling the sometimes-hidden stories and histories of the Los Angeles region. Our posts here provide a view into the archives of individuals and institutions whose collections inform the great narrative—in all its complex facets—of Southern California.