The Lost Hills of Downtown Los Angeles

In 1912, Los Angeles considered an audacious plan to reshape its topography. A group calling itself the Bunker Hill Razing and Regrading Association proposed to pump water out of the Pacific Ocean, pipe it 20 miles to the city center, and spray high-pressure jets of brine against a ridge of hills to the immediate northwest of downtown Los Angeles. In all, the project would sluice away some 20 million cubic yards of shale and sandstone that Angelenos knew as Bunker, Fort Moore, and Normal hills.

In the eyes of 20th-century business interests and civic leaders, the hills stood in the way of progress.

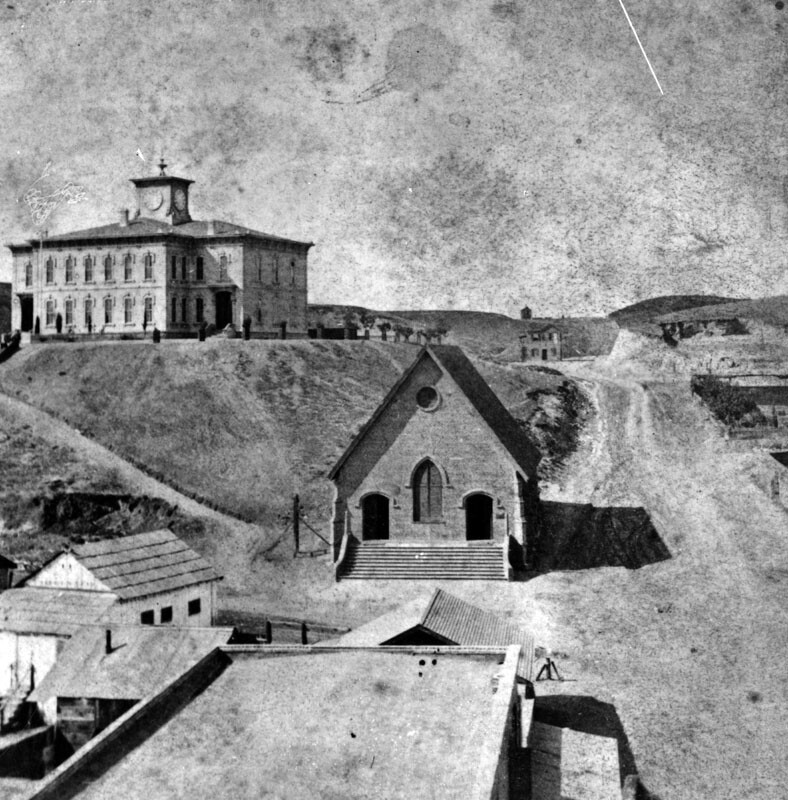

The city once prized these hills for their commanding heights. Atop them, 19th-century civic leaders placed courthouses and colleges, which floated above the city and dominated the skyline. Developers took advantage of the hilltop vistas, transforming the once-barren summits into fashionable neighborhoods.

In the eyes of 20th-century business interests and civic leaders, however, the hills stood in the way of progress.

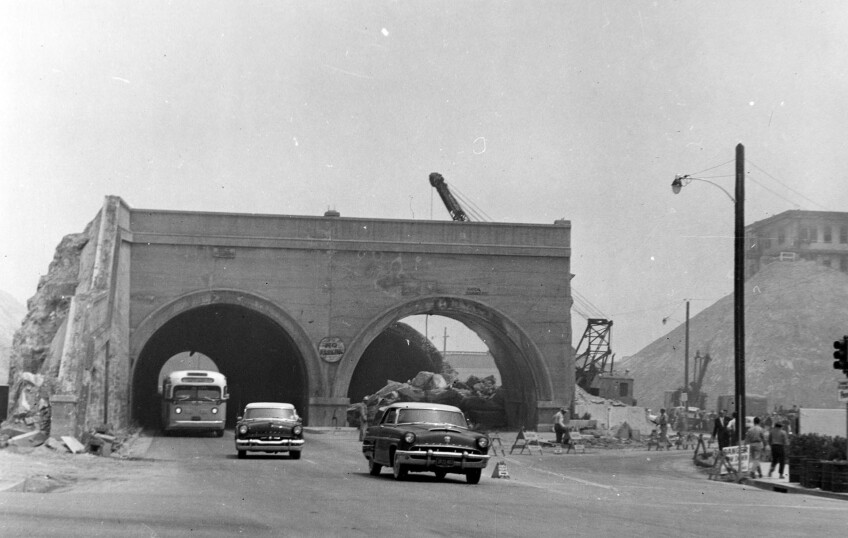

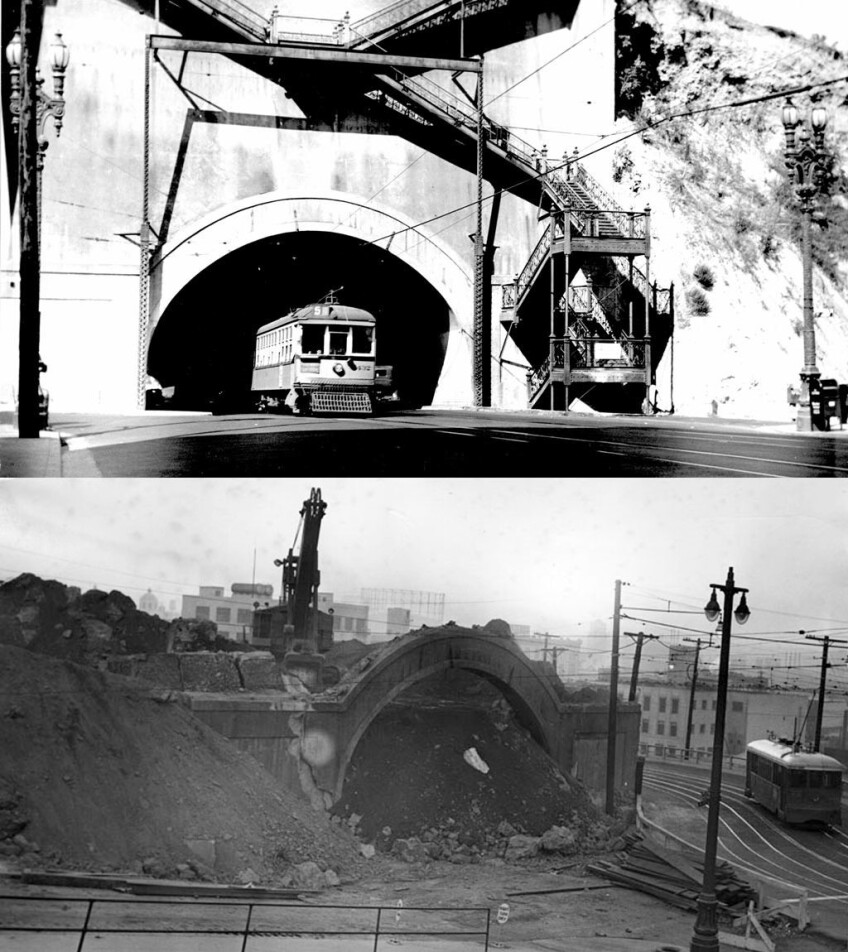

Suburbs like Hollywood and Colegrove boomed on the plains to the city's northwest, but the hills made these new towns difficult to reach from downtown by streetcar. Because they could not scale the hills' steep eastern faces, the trolleys circled around the hills, creating bottlenecks on the few routes out of downtown. At first, the city carved deep road cuts and bored tunnels into the hills to relieve congestion, but regrading offered a more comprehensive solution.

Traffic relief was not the only justification. Regrading offered the prospect of 181 acres of new, vacant real estate to a dense central business district that found itself cornered-in by the hills. The association also promised to remold the excavated earth into a series of dams and levees along the Los Angeles River, flooding the Elysian Valley (Frogtown) to form a recreational lake.

Learn more about Downtown L.A.

Ultimately rejected as impractical, the Bunker Hill Razing and Regrading Association's plan was only the first of several schemes to erase the hills from the city's landscape. In the late 1920s, before the Great Depression intervened, the city came close to adopting another plan by C.C. Bigelow, a mining baron well versed in the art of hydraulicking.

Los Angeles has never been shy about acting on the land as a geologic agent.

Los Angeles – the city that created a harbor where nature failed to provide one and later bound its unpredictable river in a concrete straitjacket – has never been shy about acting on the land as a geologic agent. And among American cities, the proposals were not without precedent. Seattle washed away 27 blocks of Denny Hill between 1908 and 1911. Portland used the same machinery to flatten Goldsmith Hill in 1912.

In the end, Los Angeles turned down the wild-eyed hydraulickers in favor of a more piecemeal approach to dismantling its downtown hills.

Poundcake Hill was the first to recede from the landscape. First known to English-speaking Angelenos as Telegraph Hill for the semaphore tower that once stood on its summit, it eventually gained a new name, derived from its resemblance to the round, plump dessert food. When the Southland's first high school rose from its top in 1873, the hill stood high above Temple Street below. Later, construction of an imposing, red-sandstone county courthouse (1891) on the site shortened the hill's stature, and after the courthouse's 1936 demolition, development of the Los Angeles Civic Center and construction of the new Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center flattened Poundcake Hill beyond recognition.

Normal Hill suffered a similar fate. The southernmost knoll in a ridge that stretched north to Elysian Park, the hill once towered 70 feet above the surrounding landscape. Prudent Beaudry opened his Bellevue Terrace gardens on the site in the early 1870s, and the hill got its name in 1882, when the California Branch State Normal School moved into a five-story building atop its summit. The teachers' college (which has since evolved into UCLA) moved to its Vermont Avenue campus in 1914, and Normal Hill soon became a casualty of downtown's crippling traffic congestion. To extend Fifth Street through the site, construction crews shaved off the top half of Normal Hill, and the construction of the Los Angeles Central Library on the site further reduced its visual prominence.

Fort Moore Hill (also known as Fort Hill) once loomed over the city's historic plaza, and during the Mexican-American War, U.S. troops built defensive fortifications that gave the promontory its name. For a time it was home to a Protestant cemetery, and it became one of the city's trendiest neighborhoods soon after Mary Banning, widow of the successful harbor-builder Phineas Banning, moved into a hilltop mansion in 1886. But during the 1930s steam shovels tore away at the hill's slopes for road extension projects, and in 1949 they carved a deep canyon through the hill for the new Hollywood Freeway. Dump trucks carried away some one million cubic yards of earth to nearby Elysian Park, and Fort Moore Hill withdrew from the landscape.

Bunker Hill, meanwhile, managed to outlast its neighbors. Victorian mansions began to rise from its summit in the 1880s, and by the turn of the 20th century it had become one of the city's most fashionable neighborhoods. Soon, however, the fashionable people moved on, and the structures they left behind took on an increasingly shabbier appearance. As the hill's population became poorer and more multi-ethnic, regrading promised to wipe clean the architectural slate and erase a community deemed undesirable by developers. In the 1960s – after securing federal funding for what was termed, in the parlance of the time, "slum clearance" – L.A.'s Community Redevelopment Agency oversaw an urban renewal program that recalled the regrading dreams of the past. Over several years, construction crews demolished the existing built environment and scraped some 30 feet of earth from the top of Bunker Hill, creating 27 virgin superblocks cleared for high-rise development.

This post was first published on KCET.org on October 13, 2011, and was subsequently expanded, updated, and republished on May 21, 2015. A different version was published on Gizmodo's Southland in December 2013.