The Lost Canals of Venice of America

Secreted away from the hustle and bustle of the famous boardwalk, the picturesque canals of Venice, California, are one of the seaside community's hidden charms. But in Venice's early years, the canals that survive today were only a sideshow. The main attraction – the original canals of Abbot Kinney's Venice of America – are lost to history, long ago filled in and now disguised as residential streets.

In planning Venice of America, Kinney incorporated several references to the community's Mediterranean namesake, from the Italianate architecture to his fanciful notion of launching a cultural renaissance there. But Venice of America would not have lived up to its name were it not for its canals.

When it opened on July 4, 1905, Venice of America boasted seven distinct canals arranged in an irregular grid pattern, as seen below in Kinney's master plan for the community. Totaling nearly two miles and dredged out of former saltwater marshlands, the canals encircled four islands, including the tiny triangular United States Island. The widest of them, appropriately named Grand Canal, terminated at a large saltwater lagoon. Three of the smaller canals referred to celestial bodies: Aldebaran, Venus, and Altair.

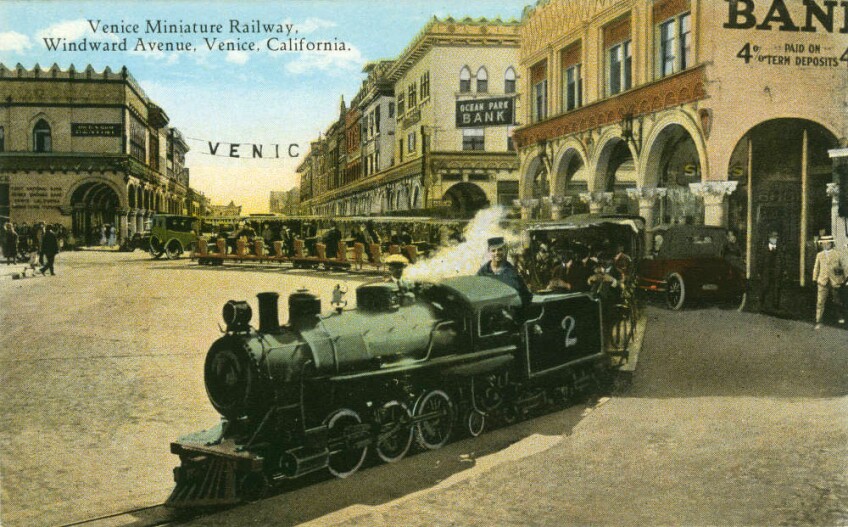

Though their primary role was to evoke the old world charm of Venice, Italy, the canals also functioned as part of Kinney's transportation plan for the development. In 1905, the automobile had barely dawned on the Southland, and so Kinney laid out Venice of America at the pedestrian's scale. Visitors would arrive by interurban streetcar or steam railroad and once there could reach the entire community and its various amusements by footpath. The canals -- as well as a miniature railroad that circled the development -- provided an alternative to walking. Gondoliers rowed tourists through the canals for a fee, serenading their passengers in Italian. Homeowners, meanwhile, navigated the system of waterways by canoe or boat.

Soon, a second set of canals appeared just south of Kinney's. Linking up with the existing network through the Grand Canal, these Short Line canals (named after the interurban Venice Short Line) were apparently built to capitalize on the success of Kinney's development. Their origins are uncertain, but work started soon after Venice of America's 1905 grand opening, and by 1910 real estate promoters Strong & Dickinson and Robert Marsh were selling lots in what they named the Venice Canal Subdivision. Built almost as an afterthought, these six watercourses are the only Venice canals that survive today.

The original Venice of America canals contributed to the success of Kinney's real estate development. Lots fronting the canals became a favorite choice for owners of the local amusement concerns or out-of-town tourists looking for a place to pitch a summer cottage. But by the 1920s, the canals had become seen as an obstacle to progress. Poor circulation meant that the water was often polluted. More importantly, many visitors were now arriving by automobile, but Venice offered scarce parking, and its streets were designed for pedestrians, not motorcars. In the eyes of business owners and city leaders, the canals looked like an opportunity to open up their community to the automobile.

In 1924, the then-independent municipality of Venice resolved to adapt its transportation infrastructure for the automobile age. The two Pacific Electric trolleyways running through the city would be widened and paved – today they're appropriately named Pacific and Electric avenues – and the canals would be filled in and converted into public roads.

Residents resisted the move. Those who lived along the canals worried that their homes would lose their waterfront appeal, and many in the community questioned the logic of a city with the name of Venice but no canals. Most importantly, property owners rebelled against a special assessment that would be levied on their holdings to finance the conversion.

Litigation lasted four years. By the time the court battles were finally resolved in the city's favor, Venice had consolidated with the city of Los Angeles, which adopted the controversial infill policy. On July 1, 1929, as dump trucks deposited their first loads of dirt into Coral Canal, public officials held a special ceremony. California Governor C. C. Young, the Venice Vanguard reported, "congratulated Venice on her foresight in sacrificing sentiment to progress."

By the end of the year, Venice's original canals had been filled in and paved over. A new underground storm drain flushed the water out to sea. Trucks then dumped more than 90,000 cubic yards of sediment into the former watercourses. Only the six canals to the south of Venice of America were spared, as the area was insufficiently populated to levy the necessary property assessment.

Entombed beneath a layer of asphalt, the former lagoon became a traffic circle, and little evidence remains today of the roads' former lives as saltwater canals. As if to protect the waterways' former identities, even their names were changed. Aldebaran Canal became Market Street; Coral Canal, Main Street; Venus Canal, San Juan Avenue; Lion Canal, Windward Avenue. Only Grand Canal retained its former name, becoming Grand Avenue.