The Golden Gate and the Silver Screen

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

In collaboration with the University of California Press and the California Historical Society, Lost LA is proud to present selected articles from California History that shed light on themes discussed in the show's second season. This article originally appeared in the Spring 1984 edition (vol. 63, no. 2) of the journal.

The beneficent climate and cosmopolitan cultural ambience of Northern California have long attracted inventive personalities and engendered creative activity. From its birth to the present day, the motion picture medium has been particularly nurtured and sustained by this unique area.

During the silent film era, even while Hollywood was coming to dominate world-wide filmmaking, many leading names came to the Bay Area to film "location scenes" for some of their most notable successes.

As early as the 1870s, the natural beauty and tonic qualities of Northern California's out-of-doors drew together photographer Eadweard Muybridge and industrialist Leland Stanford for an epic work on the latter's estate at Palo Alto in Santa Clara County. Their joint experiments resulted in the world's first split-second sequential photographs of horses, oxen, deer, birds and, finally, man in motion.

These stop-action photographs swiftly led Muybridge and Stanford to the invention of an instrument to project the separate images in rapid sequence onto a screen: the prototype of today's movie projector. To photography's already existing power of recording static physical reality, Stanford and Muybridge added the new dimension of recording reality as it changed through time. The world-wide premiere exhibition of their motion pictures took place in San Francisco in May 1880. The new medium amazed audiences with its continuous flow of realistic moving images and the variety of scenes photographed under wide, bright California skies.

The San Francisco premiere showing of the magical picture that moved stimulated technical advances on a world-wide scale. By the mid-1890s, motion picture films were being successfully exhibited in leading cities of the United States and Europe. This new marvel showed a spellbound public that scenes and events anywhere in the world could be recorded with indisputable photographic accuracy and recreated on a screen at a later time and in a distant place. Although lasting only a few minutes, the very early films demonstrated the filmmakers' utter fascination with, and rapidly growing mastery of, the new medium.

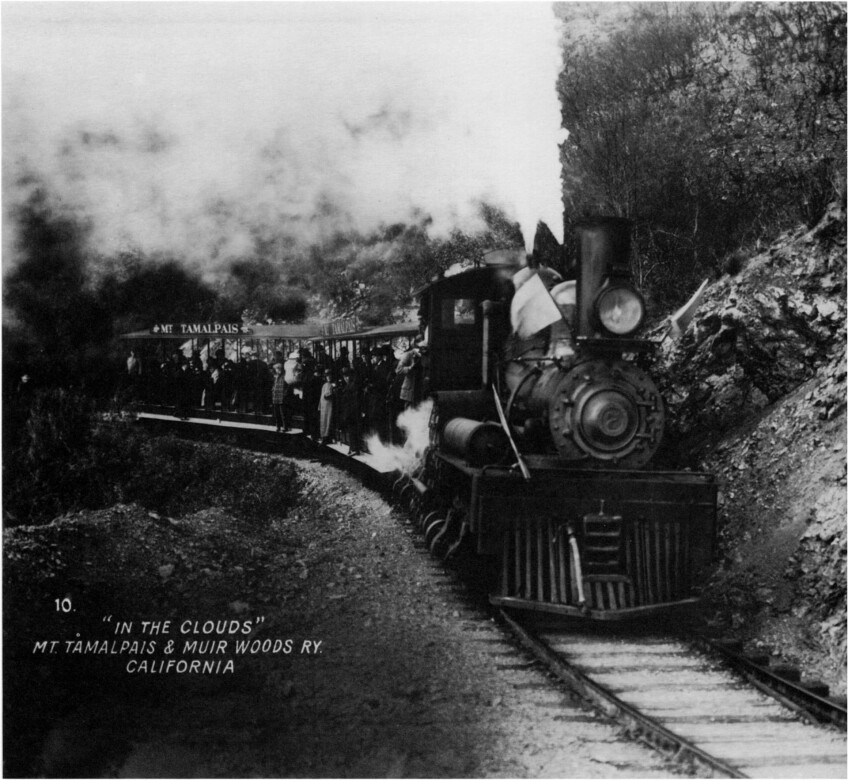

A delightful, remarkably successful early example of the cinematic capacity to capture unstaged reality was filmed in Marin County around 1900. A Trip Down Mt. Tamalpais, shot from atop a railroad car, not only recorded motion, but also created the sensation of speed and propulsion. It both thrilled spectators and provided them with a unique visual experience as the train twisted and turned down the mountain into the giant evergreen trees at its base.

Another early movie also attested to the camera's affinity for reality but in an urban setting. This was The Barbary Coast, filmed in San Francisco during 1913. As no painted make-believe stage set or verbal description could do, the camera captured the squalid structures of the waterfront vice zone with raw truth, making the picture a rare social document.

Even before this, however, filmmakers were beginning to realize the new medium's potential for entertainment. Soon, the short film which merely recorded unposed reality gave way to the theatrical film which told a story.

To find attractive settings for the new story film, producers tried filming in different parts of the United States. Among the movie hopefuls was Gilbert M. Anderson of the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. Roaming the West from Colorado to Santa Barbara in search of ideal settings for adventure stories about frontier days, Anderson finally set up his film studio near the farming and ranching town of Niles in Alameda County. From 1909 to 1916, his Essanay westerns, with their strong, dramatic action building to resounding climaxes, earned world-wide acclaim. Anderson's new character, "Bronco Billy," was the prototype for the cinema cowboy later epitomized by Gary Cooper and John Wayne. The variety and magnitude of the Northern California outdoor settings chosen by Anderson-unadorned towns with unpaved streets and wooden sidewalks, rough-hewn ranches and corrals, stream-fed valleys, rolling hills, and verdant open country helped make the Essanay films America's first true westerns.

The countryside of Northern California also inspired another well-known movie figure. No less than Charles Chaplin, an artist with Essanay Company in 1915, found in the area an environment which helped him to create his "Little Tramp" in the classic comedy, The Tramp, which was filmed in the bucolic farms and orchards of the countryside around Niles Canyon. Among the most important early film companies established in Northern California was the California Motion Picture Corporation (CMPC). As the site for its studio the new company chose Marin County – just north of the Golden Gate – with its unrivaled beauty and variety of scenic backgrounds.

Entering production in 1913, the CMPC was notable among early film companies for its high-caliber cinematography. This camera work added greatly to the success of its feature-length westerns, which were among America's first. Inspired by Bret Harte's stories from the colorful history of California, the CMPC filmed them among the giant redwoods and verdant mountains of Northern California. The company also constructed a replica of an early Western town in the majestic big trees of the Santa Cruz coastal range south of San Francisco. Such unprecedented scenic grandeur impressed national film audiences and critics. The prestigious New York Dramatic Mirror's review of Salomy Jane (1914) exclaimed:

This is creating an environment in the best sense, for it does on the screen what the author aims to accomplish in his descriptive passages: it gives the characters a true background. In the present instance it is a great, free, seemingly limit less background-towering mountains threaded with winding roads, rivers breaking their way through primal forests-the most inspiring of its kind that we recall.

Many types of films made by many different companies profited from the intriguing variety of settings lying between California's rocky coastline and the towering Sierra. Although most Hollywood exteriors were routinely shot against false-front sets and artificial greenery of the studio backlot, there were also astute producers who realized that movie dramas could gain strength, texture, and credibility if they were filmed in authentic surroundings. During the silent film era, even while Hollywood was coming to dominate world-wide filmmaking, many leading names came to the Bay Area to film "location scenes" for some of their most notable successes.

During the years of the early twentieth century when the new medium's potential was still being explored, movie makers discovered that the motion picture camera has a particular affinity for reality. While it unsparingly accentuated the flat, artificial qualities of the theater stage's painted backdrops, it endowed out-of-door scenes with depth and sweep. It was as though the boundaries of the film frame disappeared when movies were projected onto screens. Beyond the Gold Rush diggings and forest trails of Salomy Jane extended ever-wider, ever-higher mountains, beyond the teeming streets and alleys of Greed huddled endless urban slums, and beyond the weatherbeaten ranches and corrals of an Essanay western stretched California's cattle country. Cinema art brought to movie audiences a scenic environment that was as unlimited and inexhaustible as nature itself. The movies of Essanay, the CMPC, and other Bay Area studios, as well as Hollywood units on location in the Bay Area-even though only a small portion of the movies produced in the silent era stand as eloquent testimony to the visual appeal and the scenic splendor of the Bay Area.

Today, movie making is again increasingly independent of the studio lot, and as a result the Bay Area is frequent host to movie makers and television crews. While much of the environment has been urbanized, imaginative producers and directors still find inspiration in the natural and man-made beauty of the area which continues to make its mark – visually and intellectually – on the ever-developing art of the cinema