The Complex Life of Griffith J. Griffith

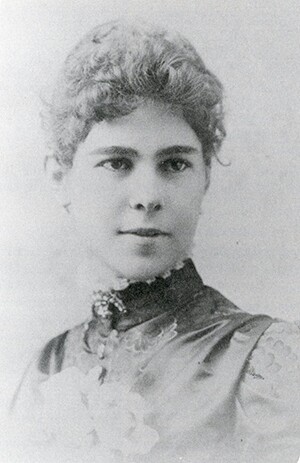

At the entrance to Griffith Park, off Los Feliz Boulevard, stands a 14-foot bronze statue of a proud, portly Victorian gentleman. He is Griffith J. Griffith, who donated 3,015 acres of the former Rancho Los Feliz to Los Angeles in 1896, to be used specifically as a park for the “plain people” of the city. His face, decidedly noble and assured, lords over his “princely gift” to the city, which is no doubt one of L.A.’s greatest public resources. While portraits and photos of Griffith are plentiful, there are hardly any in existence of his wife, Tina — from whom a great part of his fortune and prestige sprang — and none after the year 1903. Because that year, Griffith J. Griffith shot his wife in the face, permanently disfiguring her.

This very peculiar L.A. tragedy began half a world away. According to Paul McClure, author of “A Benefactor Tragedy Starring Griffith J. Griffith,” Griffith Jenkins Griffith was born in South Wales on Jan. 4, 1850, the son of a farmer who also worked for the nearby mines. The eldest of a large, impoverished brood, the young Griffith was taken to America by an uncle when he was still a child. The ambitious, brash young man was educated in Pennsylvania, and then went into the newspaper business. This trade brought him to San Francisco in the 1870s, where he worked the mining beat for the Alta California. Becoming an expert on western mines, he made his — probably much exaggerated — fortune as a consultant to mine owners.

In 1882, Griffith, drawn to the wide-open opportunities of boomtown Los Angeles, moved to the City of Angels permanently. In December of that same year, he bought the sprawling rural Rancho Los Feliz — long said to be cursed — from Thomas Bell. Griffith quickly became a well-known figure in Los Angeles, lording over his mountainous rancho astride his horse, overseeing numerous improvements. Griffith attempted to make the rancho, then outside the city limits, into a prosperous ranching operation. According to McClure, he would eventually build a rickety railway to his land and have “6,000 sheep, 50 horses, and 150 dairy cows on the rancho.”

“Were you going to make a pen portrait of him you would see a man of somewhat average height in the prime of life, of well-knit, muscular frame,” the Los Angeles Times wrote of Griffith. “Altogether a powerfully built man…Keen, dark eyes rest on you but with such an open, frank look as to inspire confidence, while the clear ringing laugh which invariably accompanies the story he is telling proclaims a man who enjoys every moment of his existence.”

Griffith also annoyed many people by forcing himself into SoCal civic life. Wags called him not only a "roly-poly pompous little fellow" with an “exaggerated strut like a turkey gobbler," but a “midget egomaniac” and a braggart. This did not stop the wealthy Louis Mesmer, owner of a large furniture store on Main Street, from introducing Griffith to his daughter Tina. The Mesmers were descendants of the legendary Verdugo family, and therefore aristocracy in rough and tumble Los Angeles. Tina and her sister, Lucy, were also the heiresses to a quarter million- dollar fortune, left to them by family friend Andre Briswalter.

Believing Tina to be the heir to the entire Briswalter fortune, Griffith began courting her. They were soon engaged, and announcements for the wedding appeared in all of the local papers. However, ten days before the wedding, Griffith discovered the Tina was only heir to half the Briswalter fortune. He wrote his betrothed a brutal letter, breaking off the engagement. Her Catholic family was appalled and begged Griffith to not disgrace their daughter in this way. He agreed to go through with the marriage, but only on the condition that Tina inherits the entire fortune — and that it be transferred to his name. Griffith claimed that this was not to steal the money, but to ensure that (according to the Times) “after marriage there would be no interference with his wife’s money on the part of her family.”

Not surprisingly, after this episode the Mesmer family would forever be wary of Griffith J. Griffith. On Jan. 27, 1887, the two were married in a society wedding the likes of which backwater L.A. had rarely seen. “By this marriage two immense estates were united,” the Los Angeles Times reported. “The large possessions of G.J. Griffith and a vast amount of Los Angeles property owned by the charming bride, Miss Mary Agnes Christina Mesmer, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Louis Mesmer, familiarly known among her most intimate society friends as ‘Tina.’”

According to the Times it was a match made in society heaven:

The bride has been educated in a superior manner, as befits the owner of so vast an estate. Her singing and playing are exceptionally fine, and her taste for flowers is remarkable (as is well illustrated in her mother’s garden). She can speak four languages, while the happy bridegroom can converse in three, including Welsh.

But the wedding was not all love and sunshine; it was about cold hard cash. As the Los Angeles Times reported years later:

At the wedding breakfast that day, even before guests had completed the meal, Griffith rose and excused himself, saying that he must go and bid goodbye to several friends before embarking on the honeymoon trip. A subsequent examination of the courthouse records showed that instead of bidding adieus, Griffith had slipped across the street to the courthouse…and within six minutes of leaving the wedding breakfast, caused the $250,000 to be transferred from the name of Mary Mesmer to that of her brother Tony Mesmer, and from the name of Tony Mesmer to the name of Griffith J. Griffith. Then he returned to his bride and the wedding party.

A year after the wedding, Tina gave birth to the couple’s only child, a son named Vandell. Now backed by his wife’s enormous wealth, Griffith continued his ascent into L.A. society, making many enemies along the way.

In October 1891, Griffith accompanied Tina and her sister in a carriage to the old Catholic Cemetery on Buena Vista Street. They were there to decorate their mother’s grave, who had died only months before. Suddenly a distressed man appeared in a carriage and shot at Griffith from a gun loaded with buckshot. Griffith was hit in the head and took off running, as Tina, according to Times, yelled after him from her carriage, “I know who it is papa!”

The man who had shot Griffith was an Englishman named Frank Burkett. Along with a Dr. Sketchly, he had leased land from Griffith to open an ostrich farm on the Los Feliz Rancho. The farm had been a dismal failure, and Burkett had fallen behind on his rent. Believing Griffith was attempting to ruin him, he had grown increasingly deranged and was suspected of setting fire to his own house on the rancho.

But the tragedy would not end there. “As soon as Burkett fired the last shot, he whipped up his horse and started for the bridge,” the Los Angeles Times reported. “He had only gone a few feet when he must have determined to take his own life, for he drew a pistol from his pocket and placing the muzzle against his head, just back of his right ear, he pulled the trigger…the bullet literally tore the back part of his head all to pieces, and brains and blood covered the side of the buggy and the street.”

Griffith was only minimally injured and soon back to his old bombastic self. During the 1890s, he was at his peak — a member of the prestigious Jonathan Club; a pioneering member of the Fruit Growing Association of Los Angeles, the Merchants and Manufacturers Association, the Citizens and Free Harbor Leagues; and the only honorary member of the Chamber of Commerce.

In 1896, his legend was cemented when he offered to donate 3,015 acres of the Feliz Rancho to the city, for use as a public park. Though his enemies, including the writer Horace Bell, claimed he only donated the land as a tax scheme because he had failed as a ranch owner, the “princely gift” was lauded by city leaders. He formally bequeathed the land to the Mayor in December 1896, after making a brief address to the City Council:

Recognizing the duty which one who has acquired some little wealth owes to the community in which he prospered, and desiring to aid the advancement and happiness of the city that has been for so long, and always will be my home, I am impelled to make an offer, the acceptance of which by yourselves, acting for the people, I believe will be a source of enjoyment and pride to my fellows and add charm to our beloved city. Realizing that public parks are the most desirable feature of all cities which have them and that they lend an attractiveness and beauty that no other adjunct can, I hereby propose to present to the city of Los Angeles, as a Christmas gift, a public park of about three thousand acres of land.

This gift garnered Griffith all the prestige he had ever hoped for. “Griffith J. Griffith,” the Los Angeles Times lauded in 1898, “though not born in America, he nevertheless is thoroughly imbued with the liberal spirit which makes up the ideal American citizen. His long residence upon the Pacific Coast has made him a thorough westerner in manner and feeling. His congeniality is his most conspicuous characteristic. His gift to Los Angeles is peculiarly fitting, he having spent the great part of his successful business career in this city and having been closely identified with its growth and development for many years.”

Now known as a “builder of cities,” Griffith was officially on the A-list of L.A. society. “He is fond of all out-door amusements, a good theater-goer, and ’first nights’ of any prominent attractions at the opera or playhouse are certain to find Mr. and Mrs. Griffith in their places as the curtain rises,” the Los Angeles Times observed. And he could often be found on his old rancho, now known as “Griffith Park.”

Not everyone was pleased with Griffith’s rise. Now styling himself “Colonel” for no particular reason, local wits began referring to him as “The Price of Whales.” A teetotaler in public, Tina claimed Griffith was a nail biter and a “sneak drinker,” who was usually drunk. “He never left the house without taking a drink,” she later testified according to the Times, “and he never came into the house without taking one, and, of course, I don’t know how many he took in between.” Their marriage began to fall apart, as Griffith became increasingly unstable and suspicious.

However, Griffith could still be counted on to perform in public. In April 1903, the Times reported that he played toastmaster at a farewell party for Hollywood pioneer Mrs. Whitley at the Hollywood Hotel in the dry rural paradise, leaving people in stiches with his “funny” remarks:

When we look at women in the abstract, or in the concrete, or even when we regard her in all the glory of an Easter transformation, what thoughts crowd upon our mind. Human intelligence cannot estimate what we owe to women, it has been said that she sews on our buttons — but the laundryman does that now. She ropes us in at church fairs, but then we are a willing sacrifice. She confides in us when she is figuring for a new dress. She gives us good advice — and plenty of it. She gives us a piece of her mind sometimes — and sometimes all of it. Wheresoever you place a woman, in whatever position or estate, she is an ornament to the place she occupies, and a treasure to the world.

Only a month later, Griffith would threaten Tina with a gun for the first time, in their apartment at the Hotel Freemont. “I had threatened to leave,” she testified later according to the Times. “And I think he realized that I would not stand it much longer. It had certainly come to the question. He is very proud and did not want the public to know.”

Despite the strained, abusive marriage, during the summer of 1903, Griffith, Tina and Van stayed together in the presidential suite of the grand Hotel Arcadia in Santa Monica. Griffith had believed all summer that someone was trying to poison him and would constantly make servers switch out his soup in the Arcadia dining room. On the evening of Friday, Sept. 4th, Tina was packing, preparing for their trip back to Los Angeles, when Griffith entered their room.

Griffith was holding a gun. In his other had was a prayer book. “Would you swear on this prayer book the same as you would on a Bible?’” he asked. He then told Tina to kneel and began peppering her with other questions. “Did you ever hear or know anything about Briswalter being poisoned?” he asked. “Have you been implicated with or do you know of anyone giving me poison?” Tina later recalled what happened next, as reported in the Times:

His third question was, ‘Have you always been faithful to your marriage vows?’ I said: ‘As God is my Judge, I have, and you know that I have.’ As I answered my last question, he shot me. I was on my knees, and I jumped up and rushed for the window. It was closed but I managed to raise it and get out. I sprang out and fell to the roof below.

According to McClure, “the bullet entered her forehead but miraculously split in two, one part of the bullet ranged upwards along the frontal bone of her forehead and the other part of the bullet sped downward tearing out her right eye.” Miraculously, Tina lived, and was quickly found by a couple in the suite below. As writer Adela Rogers St. Johns would later say, Tina was “the society wife who wouldn’t die.”

Tina was rushed to the hospital where she would stay for almost a month. Griffith was arrested three days later, in the middle of an epic bender. His trial for attempted murder that fall was the talk of Southern California. Griffith’s lawyer, the brilliant (also alcoholic) Earl Rogers, claimed that his client had been seized by “alcoholic insanity” and therefore was not responsible for his actions. On November 3 ,1903, Tina, now blind in one eye and horribly disfigured, appeared to testify. The Los Angeles Times reported breathlessly:

An inner door of the courtroom opened, and a procession of handsomely dressed women swept in. Among them was a slight, girlish woman heavily veiled and wearing black glasses…that was Mrs. Griffith. Her features could not be seen. The ladies with her were…her sister, niece and brother…Mrs. Griffith went at once to the witness stand and faced the staring crowd. Not a sign between her and her husband. She looked at him casually as though he were someone she had never seen. Col. Griffith leaned back in his chair with his chin propped on one hand and listened almost without moving a muscle.

After hours of brave, straightforward testimony Tina fainted, before coming back in the afternoon to endure further questioning. Griffith was sentenced to only two years in prison. During his time in jail at San Quentin, the once princely Griffith worked in the laundry. Tina was granted a divorce, cash and custody of Van. When Griffith got out of jail only 20 months later, Adela Rogers St. Johns claimed he was a humble, changed man.

After his release, Griffith became interested in prison reform and restoring his important name. After a visit to the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1908, he exclaimed, "If all mankind could look through that telescope, it would change the world." This led him to begin dreaming of an observatory at Griffith Park, of course named after himself.

Griffith was furious with the slow improvement at the park which bore his name. Little had been done to make the park accessible to the “plain people’ he had so wanted to reach, and in 1910, he self-published “Parks, Boulevards and Playgrounds” under the guise of the Prison Reform League Publishing Company. In it, he wrote:

For the last fourteen years a majority of the Los Angeles City Council has claimed persistently that, owing to “lack of funds,” the city could not afford to build a road to Griffith Park or take other steps that would make it accessible to the public. I had reasons, however, to expect that my donation would receive different treatment this year, and accordingly, I postponed the publication of this little book. But when the budget committee met, July 29, 1910, the same plea was urged once more, and a Park Commissioner, who has been advocating the spending of 100,000 on central park declared that rather than stint on the work there he would cut out the 25,000 appropriation for Griffith Park.

The little book is a strange mishmash of true philanthropical beliefs and whiney grievances. “Public parks are the safety valves of cities,” he writes. “They are the pleasure ground of the people. Nothing conduces more to the public health, and money wisely spent on them is the best investment any city can make.” The book included paparazzi-like pictures of people hauling sand and gravel illegally out of Griffith Park, private houses erected in its pasture, horses, sows and mules illegally grazing, and even a private dairy. Under each photo is the caption: “Would such mistreatment induce others to make donations to the city?”

In 1912, the still wealthy Griffith offered the city money to build an observatory, and in 1913 he offered money for an outdoor theater. The city, wary of accepting any more gifts from an attempted murderer, declined his offer. However, after his death in July 1919 of liver disease, the city did accept the money he left in trust for both these projects — and thus the flawed, complicated man is responsible for the construction of both the Griffith Observatory and Greek Theater. And what of Tina? She lived as a virtual recluse with her sister Lucy’s family, dying after a long life in 1948.

Top Image: View of Griffith Observatory from Griffith Park beneath a tree | Patrick T'Kindt / Unsplash