The Birth of the Universal Studios Tour

Union Bank is a proud sponsor of Lost LA.

By March of 1914, Carl Laemmle's Universal Film Manufacturing Company needed more land. Laemmle and his partners founded the company in the spring of 1912 in New York, merging the new venture with several already-established film production companies. The merger gave Universal the use of the Champion Film Company studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, the film production capital of the world at the time. Already a seasoned nickelodeon owner, Laemmle recognized that producing his own films would enable him to avoid both hefty licensing fees and production regulations imposed by Thomas Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC). Still, Fort Lee's inclement weather and Universal's ongoing legal challenges from the MPPC made New Jersey inhospitable. Laemmle, along with a handful of other film producers, fled west.

More on early Hollywood and Lost LA

After arriving in Los Angeles, Laemmle took control of the Nestor Film Company production facility, which delivered Hollywood’s first films. Nestor's staff churned out three pictures a week from their studio, a former tavern rented from widow Marie Blondeau. The building conveniently offered multiple rooms and spacious grounds at the corner of Hollywood and Gower, enabling several films to be shot simultaneously. When a script called for a more expansive location, Nestor’s crews shot in the San Fernando Valley on land leased from the Providencia Land and Water Development Company. However, lugging equipment and personnel on location required precious time and money. In order to increase efficiency and profits, Laemmle determined to consolidate Universal’s holdings. Laemmle decided to build the world’s first city dedicated entirely to making movies.

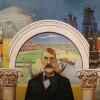

Laemmle purchased 230 acres of land in the valley for $165,000 and started construction. Ignoring his colleagues’ jeers, who often referred to the decision as “Laemmle’s Folly,” the burgeoning movie mogul hired hundreds of workers to realize his vision. While filming continued on the grounds, Laemmle installed sets and stages as well as a bank, post office, school and zoo. Laemmle even hired a group of Native Americans to perform in his films and live on the property in tepees. Following a year of construction, the city, with a population of almost 500 actors and stagehands, neared completion and Laemmle planned his grand opening.

In March of 1915, Laemmle spent eight days on a train traveling from Chicago to Los Angeles to drum up publicity for the official opening of Universal City. To celebrate his creation, now the largest film production facility in the world, Laemmle arranged for two days of festivities that included a parade, a western shootout culminating in a flash flood, and an air show. Thousands of spectators cheered the breathtaking spectacles on the first day. The excitement came to a tragic end on day two however, when a hired aircraft suffered a weather-related crash, killing the stunt pilot. Though Laemmle dispersed the crowds and closed the studio, he retained the notion of inviting people into his movie city.

Laemmle soon reopened Universal City to the public. Anyone with 25 cents for admission could thrill to the performances of their favorite film stars, while another nickel bought a boxed chicken lunch! Laemmle erected bleachers around the studio sets, encouraging audiences to cheer the heroes and boo the villains as the actors mugged for the cameras. Between takes, patrons could wander around the stages, collect autographs and visit the zoo, and the tour remained popular for over a decade. Then, with the advent of sound recording, which required a quiet set, the first version of the studio tour was put an end for nearly three decades.

Universal Studios, by then a division of MCA, officially opened its doors to the public again in 1964. Studio patrons purchased tickets for $2.50 and boarded a custom-designed pink and white Glamortram. The 90-minute guided tour included behind-the-scenes access to film and television production, costume exhibitions and an updated version of the western shootout and stunt show. The Glamortrams also stopped at the studio commissary halfway through the tour where, for an additional fee, guests could have lunch.

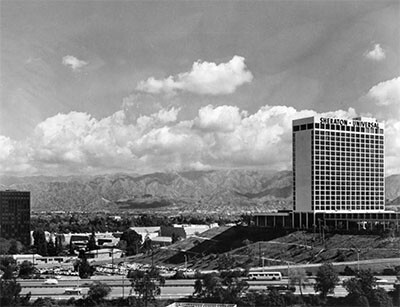

The new tram tours proved wildly popular, and MCA/Universal devoted more resources to the attraction. Universal City added a hotel to accommodate tourists, as well as a burning house, a rockslide and a collapsing bridge to the tour experience. Following the success of Steven Spielberg’s 1975 blockbuster “Jaws,” ride designers built a 25-foot mechanical shark to menace the passing tram. The tour continued to grow and evolve with new attractions and shows. Over the ensuing decades the behind-the-scenes aspect of the Glamortram tour became less important. In its place grew a theme park with rides and exhibitions devoted to movies and celebrating all things Universal.

At over 400 acres, Universal City now includes the studio’s backlot and offices, an outdoor mall with restaurants, hotels and the theme park. The flagship location of Universal Parks and Resorts, Universal Studios Hollywood hosted over nine million visitors in 2017 as ticket prices climbed to over $100 each — lunch not included. Universal operates theme parks with similar tours in Orlando, Japan and Singapore, with plans for new parks in Beijing, South Korea and Moscow. The current satellite studio tours are equally as successful as those in Hollywood, despite Universal not operating actual film studios in those locations.

Carl Laemmle envisioned a city dedicated to the movies. The studio tour, once simply a method of attracting audiences and publicity to Universal Films, transformed over time into a worldwide empire with revenues in the billions. While most early film studios are now mainly fading celluloid and memories, “Laemmle’s Folly” continues to grow in popularity, offering new generations of film lovers the chance to go behind the scenes.

Top Image: Photograph of filming a western movie on the Front Lot Stage at Universal City, ca. 1915 | California Historical Society at University of Southern California Libraries