The Balloon Route: A Tourist's Trolley Trip Through Early-1900s Los Angeles

Before tour buses roamed the region, tourists saw the Southern California seaside sites on day-long trolley trips operated by the Pacific Electric. The most popular was the Balloon Route that boasted “10 beaches and 8 cities” and “101 miles for 100 cents in 1 day.” City, agricultural, and ocean vistas swept past sightseers seated in attractive parlor cars and entertained by tour guides. During the tourist high season, an average of 10,000 people rode the Balloon Route each month. While other routes like the Old Mission, Mt. Lowe and Triangle Trolley were popular, the Balloon Route was “the showpiece of the streetcar system,” wrote Norman Klein in "The History of Forgetting."

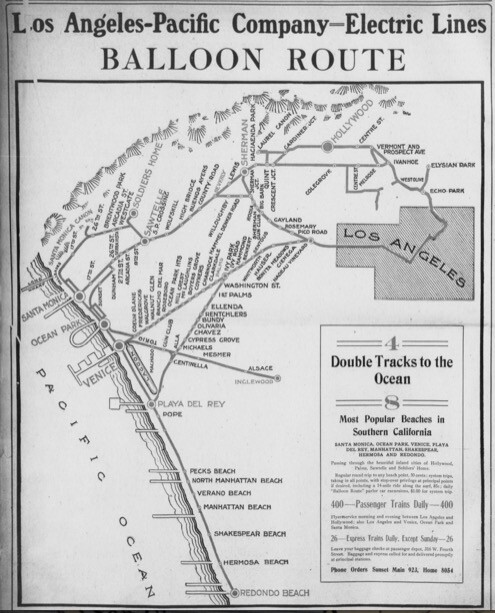

Unlike today’s tour buses, the Balloon Route operated with an ulterior motive: to entice potential homeowners to buy property, owned by the railway developers, along the route. As Klein wrote, fancy Balloon Route brochures were “pitched at Sunday workman and his family, riding in imperial splendor to the ocean, where inexpensive property was listed for sale (land along the beach was cheaper than downtown, at that time.)” While the Balloon Route’s eventual success was attributed to promoter Charles M. Pierce, the trip was initially conceived by land developers Moses Sherman and Eli Clark, who created the route as part of their Los Angeles Pacific Railway company. The pair had been methodically buying, building, merging and (in some cases) losing railway lines in Southern California, starting with the Pasadena and Los Angeles Electric in 1895. Debuting in 1901, their Balloon Route crisscrossed much of their Westside and seaside properties.

The Balloon Route did modest business under Sherman and Clark but it really flourished once Charles M. Pierce was hired as manager. Pierce had a knack for engaging tourists profitably. Before he was hired by the railway, Pierce led horse-drawn carriage tours that ended by bringing visitors to his Glen Holly Hotel in Hollywood. In a 1955 interview archived by the Pacific Electric Historical Society, Charles M. Pierce detailed his strategy for publicity:

We went to work assembling a staff of guides and advertising men. For guides I hired big men of commanding presence. When they said anything, the people listened. The advertising men drummed up business for us. We printed thousands of circulars describing the attractions of our trip and these the advertising men distributed. One man made the rounds of the large downtown hotels, another rode the Catalina steamer daily, and another rode other excursions, such as the Santa Fe's Kite Trip.

Visitors boarded the Balloon Route in downtown Los Angeles. “Balloon Route” signs hung from each train. Upon exiting downtown through tunnels, passengers rode past Echo Park, Sunset Junction (then Sanborn Junction), and into Hollywood and the Cahuenga Valley.

Hollywood

The Balloon Route’s first significant stop was the beautiful garden owned by French artist Paul de Longpre, Hollywood’s “King of Flowers.” Considered one of Hollywood’s first tourist attractions, de Longpre’s mansion and garden sat at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Cahuenga. Pierce had the train parked in a spur – a remnant of an old freight station across the street – so that tourists could easily disembark. “Tourists who missed seeing the gardens and gallery was said to not have done Southern California. Real estate men could depend on de Longpre to be the first stop when showing prospective Midwesterners local land for sale,” wrote Gregory Paul Williams in "The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History."

Sawtelle Soldier's Home

The next major Balloon Route stop was the Old Soldiers Home, officially named the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. This campus for Civil War soldiers who fought for the Union was built on land donated by John P. Jones and Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker, who believed the facility would help stimulate economic development. While the campus (now the Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Healthcare Center) may not rank high on most modern-day tours, the Soldiers Home was a popular attraction 100 years ago. In fact, visitors were encouraged to tour the campus’ sweeping landscapes and bucolic gardens. The train depot still stands (as Building #66) and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At this stop, Balloon Route passengers posed for a souvenir photo on the steps of the Soldiers Home dining hall. A photographer hired by Pierce then rushed back to downtown to process the photos and met the trolley at the Vineyard station, in time to sell the photos to passengers on the cars returning to downtown.

Santa Monica’s Long Wharf

Billed as the world’s longest pier, the Long Wharf opened in Santa Monica Bay in 1894 as Port Los Angeles. While riding over the wharf’s 4,720 feet, Balloon Route passengers were told they were on “the only ocean voyage in the world on wheels.” Built by the Southern Pacific, the wharf was meant to compete with the rudimentary harbor in San Pedro Bay by receiving freight and passengers arriving from San Francisco. Unfortunately, these assumptions “proved to be seriously flawed,” according to Joseph P. Schwieterman, author of "When the Railroad Leaves Town." “The massive facility could not begin to fulfill the lofty expectations of Southern Pacific’s leaders and gradually faded in importance.” When it was clear that the municipal harbor would be built in San Pedro, the Southern Pacific leased the wharf to the Los Angeles Pacific. By this time, “Port Los Angeles had become a ghost of its former self…and the big daily event was the arrival of the Balloon Route excursion,” according to William Myers and Ira Swett. By 1933, all traces of the pier were removed in the area is now known as Pacific Palisades.

Camera Obscura

Further down the coast, passengers disembarked at Santa Monica to visit the Camera Obscura, “a novelty with strange powers of concentration,” as described by the Santa Monica Outlook in 1898. Built by Robert F. Jones (nephew to one of Santa Monica’s founders), the attraction opened to the public in April 21, 1899. The cost to see this 360-degree view of the beach was ten cents, but was free for Balloon Route riders as it was covered by the cost of the trolley ticket. In his 1955 interview, Pierce remembered that the Camera Obscura always impressed and suggested that “this unique attraction…will no doubt be with us for many years to come.” It remains one of the few Balloon Route attractions still in operation though it is now housed in a senior center in Santa Monica.

Playa del Rey Pavilion

By the time Balloon Route passengers reached Playa del Rey (now Marina Del Rey), it was time for a fish dinner in the three-story pavilion next to the scenic lagoon. Inside was a dance floor, bowling alley, and skating rink. Passengers even had time for a brief boat ride in the lagoon. The resort at Playa del Rey was built by Henry Barbour and his Beach Land Company, which named Moses Sherman as its vice president. Sherman and Clark extended their Los Angeles Pacific to “The Kings Beach” and expected the attractions to help sell adjacent property. At the height of its popularity, the Balloon Route ushered 2,000 tourists through Playa del Rey on an average weekend. In 1913, fire destroyed the hotel. The lagoon is now part of Del Rey Lagoon Park.

Redondo Beach

The next stop was Moonstone Beach, now part of Redondo Beach. Before it was outshined by other beach cities, Redondo Beach was a popular destination for visitors arriving by train and steamship. In addition to its huge “salt water plunge,” tourists also gathered moonstones, which washed up on the beach in those early days. According to Pierce, “moonstones were sought after and many of our guests turned up excellent specimens after only a short search. These they could later sell, for stores bought them by size, or they could have them polished for a half dollar and have something very nice.” Many of the moonstones were ground into construction material for nearby development. In Redondo, streets are still named after gemstones (Agate, Beryl, Diamond, Emerald, Garnet, and Opal) inspired by the original moonstones once found on the beach.

Venice

After Redondo, the Balloon Route double-backed toward Venice, giving passengers an hour to explore the L. A. Thompson Scenic Railway, the Venice Aquarium, and the Ship Cafe.

The L. A. Thompson Scenic Railway in Venice was just one of a series of “scenic railways” – better known today as roller coasters – across the country, all modeled after the first on Coney Island. LaMarcus Adna (L. A.) Thompson built the first “gravity pleasure ride” on Coney Island in 1884. While his competitors built faster and larger rides, Thompson added scenic vistas, which proved so popular that he opened 50 more “scenic railways” across the U.S., Europe, and Australia. With its tunnels and mountain tops (a faux elk stood atop one peak), the L. A. Thompson Scenic Railway was a crowd favorite when it opened in Venice in 1910. A month after its April opening, the Los Angeles Herald reported that it seemed “to give all the thrills advertised, judging by the yells emitted by those who take the hair-raising trip.” A year after the scenic railway opened in Venice, Ocean Park built its own L. A. Thompson Scenic Railway called the Dragon Gorge, which featured biblical scenery.

Built in 1909, the Venice Aquarium displayed leopard sharks, seahorses, crabs, lobsters, food fish (e.g. bass and cod), star fish, octopus, and sea lions. Abbot Kinney’s wife Margaret even named one sea lion “Venice” and called him “Ven” for short. In addition to the fish tanks, lecture rooms and a laboratory provided educational opportunities for local students. Two years later, the aquarium became USC’s Venice Marine Biological Station, through it burned down in 1920. After Venice, the Balloon Route used the tracks of the Venice Short Line, which sped passengers back to downtown in about 50 minutes.

Coda

By the 1920s, interest in tourist trolleys declined as the automobile replaced the train as the sightseeing vehicle of choice. Today only a few Balloon Route attractions remain, like the Camera Obscura and the canals of Venice Beach. A handful of historic buildings from the Soldiers Home still stand but the campus is no longer considered a “must-see” for tourists.

As for Charles Pierce, he stopped managing the Balloon Route after a 1911 corporate restructuring dubbed “the Great Merger.” By then, he had already started other “balloon routes” in San Francisco and San Diego. He did return in 1913 to lead tourist trolley trips to the San Fernando Valley, which is about the same time the Los Angeles Aqueduct made land in the Valley more attractive to homeowners. He continued to live in the Los Angeles area well into his nineties, celebrating each of his nonagenarian birthdays with a hike to Griffith Park’s Mt. Hollywood until his death in 1964. In his 1955 interview, Pierce fondly recounted the poem he often recited for Balloon Route passengers:

Away in the merry Southland,

Far down where the oranges grow---

In the land of the great busy city,

Where angels were lost long ago---

There's a way to forget your troubles,

For a day to be brimful of fun,

And the jolly Balloon Route Guide

Will show you how it is done.

"Not up in the air he takes you,

Though you'd think you'd left the earth

For weariness, trouble, sorrow or care

Have no place in this car-load of mirth;

Then away and away he will speed you,

Through fairy land down to the shore;

Then back to real life he'll leave you at nights,

With a feeling, yes a longing, for more.

Further Reading

Pacific Electric Historical Society. "Charles Merritt (C. M.) Pierce and the Los Angeles Pacific Balloon Route Excursion.” Accessed June 6, 2016. http://www.pacificelectric.org/pacific-electric/western-district/charles-merritt-c-m-pierce-and-the-los-angeles-pacific-balloon-route-excursion/.

Los Angeles Magazine. “CityDig: DayTrippin’ on The Pacific Electric Trolley.” Accessed June 6, 2016. http://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-daytrippin-on-the-pacific-electric-trolley/#sthash.ew0R6gj8.dpuf

Crump, Spencer. Ride the big red cars; how trolleys helped build southern California. Los Angeles: Crest Publications, 1962. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000970715

Sweet, Ira and William A. Meyers. Trolleys to the Surf: The Story of the Los Angeles Pacific Railway. Los Angeles: Interurbans, 1976.