Southern California's First Amusement Parks? Ostrich Farms.

Today, thrill rides, special-effects shows, and elaborate recreations of fantastical worlds draw tourists to places like Disneyland and Universal Studios. But in the late nineteenth century, some of Southern California's first amusement parks offered visitors up-close encounters with an ornithological curiosity: the ostrich.

Ostriches arrived in Southern California in 1883 when English naturalist Charles Sketchley opened a farm devoted to the tall, flightless birds near Anaheim, in what is today Buena Park. Sketchley's investors, who included developer Gaylord Wilshire (of Wilshire Boulevard fame), organized as the California Ostrich Farming Company and contributed $80,000 to the enterprise.

The first farms capitalized on a trend in women's fashion that favored ostrich feathers for muffs, hats, and boas.

The farm – the first of its kind in the U.S. – capitalized on a trend in women's fashion that favored ostrich feathers for muffs, hats, and boas. Until 1883, only ostrich feathers shipped at great cost from the birds' native continent of Africa were available for these luxury accessories. Sketchley, who had previous experience managing ostrich farms in South Africa, envisioned fortunes built upon locally sourced ostrich feathers.

His were not unreasonable dreams; in the 1880s, exceptional ostrich feathers could fetch as much as five dollars a piece on the market, while a single mature bird could produce $250 worth of feathers each year.

The farm's first flock numbered 22 birds and arrived on March 22, 1883. They were a hardy bunch; the pioneer ostriches were the survivors of a perilous voyage from Cape Town that claimed nine out of every ten birds that boarded the ship.

Though Sketchley had brought the birds to Southern California for their plumage, they soon attracted the interest of local sightseers who were transfixed by the sight of the flock. By October, 100 to 150 visitors from across the region were touring his farm each day. Though tourism presented Sketchley with operational challenges – some visitors tried to pluck feathers themselves, and the sight of a single dog could terrify the flock for hours – the farmer soon grasped the opportunity for profit and began charging 50 cents for admission.

In 1885, Sketchley partnered with landowner Griffith J. Griffith and moved his operations to Griffith's Rancho Los Feliz, building a new farm on an oak-dotted ledge above the Los Angeles River at what is now Griffith Park's Crystal Springs picnic area.

Sketchley's enterprise attracted national attention. The New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, and Scientific American all ran reports from awestruck correspondents who seemed to delight in describing the high-strung and ungainly birds.

"To those who are unfamiliar with the appearance of an ostrich, it may be described as resembling nothing more than a large gas pipe set on tall and muscular legs," wrote a correspondent for the Tribune.

"An ostrich is apparently the most ill-tempered bird in existence. They never acquire a fondness for anyone," wrote the New York Times. "They are always on the lookout to kick someone, and if the kick has the intended effect it is pretty sure to be fatal."

Harvesting the birds' economic value, then, was a delicate process.

The Rancho Los Feliz ostrich farm may have inspired Griffith G. Griffith to donate much of his real estate as public parkland.

"A curious fact about the bird is that it never kicks unless it can see its adversary," explained the Tribune. "The ostrich men have utilized this peculiarity, and before plucking draw a long stocking down the neck of the birds, completely blindfolding him."

The margin for error was thin: "One of the keepers overlooked a hole in the stocking recently and had a narrow escape," the Tribune's correspondent added.

Sketchley's farm attracted interest from local investors, too. Beginning in 1886, nearby landowners built an Ostrich Farm Railway to transport curious sightseers back and forth from central Los Angeles. At one point, five trains a day steamed into the farm's depot.

Financial difficulties soon forced Griffith and Sketchley to close their operation in 1889, but despite its short lifespan it left a lasting legacy. Local historian Mike Eberts suggests that it inspired Griffith to later donate much of his real estate to the city as public parkland. The Ostrich Farm Railway, meanwhile, became part of the first great electric railway linking Los Angeles to Santa Monica, and its winding route through the hilly terrain of what's now Echo Park and Silver Lake became Sunset Boulevard.

The Rancho Los Feliz farm also spawned imitators across Southern California, aided by region's climate and booming tourism trade. By 1910, Southern California boasted ten ostrich farms.

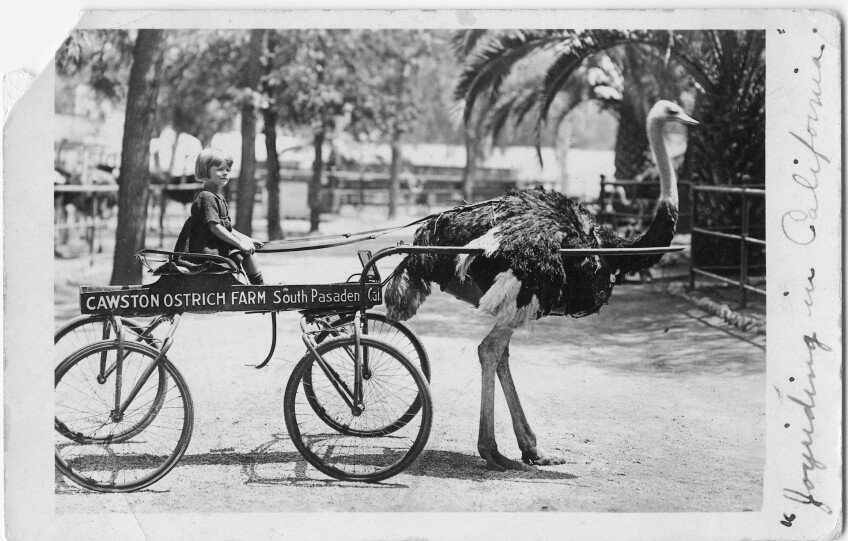

Among the most visited was Edwin Cawston's farm, which opened near Norwalk in 1886 and in 1895 relocated to South Pasadena. Located conveniently along a Pacific Electric interurban rail line, the farm attracted so many visitors that Cawston eventually moved his breeding operations to Perris, reserving his South Pasadena location exclusively for tourism.

Also popular was the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm, which opened in 1906 next to the California Alligator Farm in East Los Angeles (since renamed Lincoln Heights).

One highlight was feeding time, when tourists would gawk at the birds as whole oranges slid down their flexible gullets.

In the 1910s, the market for ostrich plumes collapsed, but tourists continued to flock to the farms well into the twentieth century. Visitors rode in ostrich-drawn carriages and wagons or even, in some cases, rode the birds bareback. One highlight was feeding time, when tourists would gawk at the birds as whole oranges slid down their flexible gullets. Before leaving, many guests stepped into the farms' gift shops, which sold boas and other souvenirs made of ostrich feathers.

Eventually, tourists found new sources of diversion, and the ostrich farms gave way to amusement parks with more elaborate and thrill-seeking themed attractions. The famed Cawston farm in South Pasadena shut its doors in 1934, and the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm -- the last of its kind in Los Angeles – closed in 1953.